Issue 191

July 2020

And when it came to getting MMA back on the road, it was always going to be the UFC leading the way. Here’s how the organization made it happen

If comebacks are considered the cornerstone of all sports, it could be argued there are no greater or more dramatic comebacks than the ones witnessed in mixed martial arts. Violent, shocking, and often entirely unexpected, the comebacks produced in MMA can occur in the blink of an eye during a fight or can instead arrive in the form of the life lessons a fighter offers when successfully rebounding from defeat.

Either way, MMA is very much a sport predicated on the ideas of refusing to be denied, never giving up, and learning from setbacks; a sport for which a precarious situation offers only a chance to rebound, to grow and to confound expectations. It is a sport analogous to life. A sport like no other.

It came as no real surprise then that the Ultimate Fighting Championship [UFC], one of many organizations floored as a result of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, was the first to show signs of life, brush itself down and signal its intention to rise before the count had reached ten. As those around it shook their heads and advised it to stay down and wait it out, the UFC was adamant. It said it would get up and continue as normal – or as close to normal as conditions would allow – and now, three events later and with plans to launch a UFC Fight Island, it has successfully cleared its head and returned to the fold. The UFC brought combat sports back first – from the brink.

Against all the odds, the UFC came back. Up and running again, if not yet at full speed, certainly paving the way for other mixed martial arts organizations, as well as other sports, to follow suit in the coming weeks and months. It has come back at a time when everyone else was saying the idea was inconceivable. The UFC defied expectation. In staging three shows in eight days, it proved its doubters wrong.

It started on May 9 with UFC 249, at the VyStar Veterans Memorial Arena in Jacksonville, Florida, and continued with subsequent events headlined by Glover Teixeira vs. Anthony Smith [May 13] and Alistair Overeem vs. Walt Harris [May 16] respectively.

The UFC 249 card, a pay-per-view event, was initially scheduled for April 18 in Brooklyn, New York, but postponed due to the coronavirus outbreak. An attempt to then shift it to tribal lands in California was cancelled when the UFC came under pressure from leading executives at Disney, which owns the UFC’s American broadcast partner ESPN. Yet if anyone thought that was going to stop the UFC going ahead, they were mistaken.

It was inevitable really. For as much as MMA specializes in comebacks and this sense of defying the odds, it is also a renegade sport, this most cavalier of sports, and by far the most likely of the world’s sports to steal a march on other pursuits. As the alpha male of the pack, the UFC, once fixed on the idea, got on with it, took the gamble, and produced three successful events with a minimum number of hitches and a maximum amount of attention. People didn’t just tune into watch them, they demanded more of them. They thanked the organization for providing sports entertainment at a time when they were fast running out of boxsets to binge on Netflix.

You could feel it – this gratitude – which was extended towards the UFC from fans. It was tangible, understandable, and even Donald Trump, a President after Dana White’s own heart, issued his support before the UFC 249 broadcast. Trump said, via recorded message, “I want to congratulate Dana White and the UFC. They’re going to have a big match. We love it. We think it’s important. Get the sports leagues back. Let’s play. Do the social distancing and whatever else you have to do. We need sports. We want our sports back. Congratulations to Dana White and UFC.”

It wasn’t all plain sailing, however. Nor, of course, did anyone expect it to be.

Ronaldo ‘Jacare’ Souza, the Brazilian middleweight set to face Uriah Hall, had suspected he might test positive for Covid-19 when arriving at the fight hotel during the first fight event, having had the virus in his family, and his instincts were correct. This meant his fight with Hall was immediately cancelled and Souza, as well as his two cornermen (who also tested positive), was then quarantined. It also acted as the proof some were looking for to further lambast the UFC for putting other fighters and their own staff at risk, as images of Souza, fist-bumping people and mixing with other fighters on the card with the two-metre social distancing rule seemingly forgotten, began to circulate.

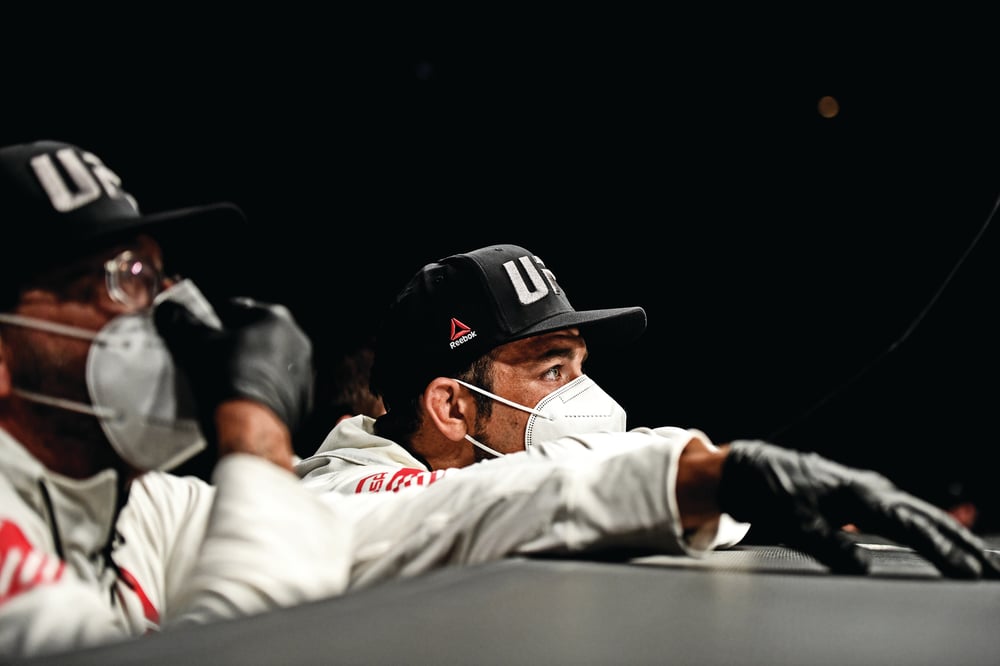

Even so, UFC president Dana White’s tenacity was unrelenting. Happy to stand close to the fighters during their head-to-heads, he would fist-bump them when they arrived on stage and seemed somewhat irked when Jacare and Hall, both wearing masks and gloves, decided to keep their distance rather than initiate a standard face-off. White had been tested, and so too had the middleweights, but the results, at that stage, had yet to come through. His stance, ultimately, was both in keeping with his approach from day one: that the show must go on, under extreme testing conditions.

That Souza’s issue was picked up was reassuring and, indeed, White reported that in total 1200 Covid-19 tests for 300 staff and fighters had been undertaken during the week. In addition to this, teams and staff working the event throughout the week were issued guidelines on such things as using workout mats, the sauna, and even ordering food from the hotel. Moreover, a letter to the fighters and their managers outlined that “the only people allowed into the hotel with our group will be our designated staff, athletes on the card and their licensed cornermen. Additional guests, such as family, friends, managers, additional training partners, will not be allowed. Fighters will have individual workout rooms and a personal sauna, and all teams will go through a mandatory medical screening process and tests on arrival, which will take place daily, with an obligation to wear an event week credential that must be worn at all times while on hotel property.”

The UFC were making their own set of rules because they had no other choice. They were, after all, guinea pigs for the rest of the sporting world. They were guinea pigs in terms of the testing procedure and how that would work and they were guinea pigs also in terms of how the fight night set-up would operate and look and how the TV crew would go about delivering a product without fans and the usual razzmatazz that tends to be the backbone of a major sporting event. “Go on then, you go first,” appeared to be the message from the rest of sporting world and the UFC, to their credit, didn’t have to be asked twice. With seemingly no fear of failure they went ahead with what they had planned and showed that the finished article, though markedly different to their usual offering, could still work and still be as entertaining as it might have been with crowd noise, commentators sitting alongside each other, and with the foot of caution moved away from the brake pedal.

Make no mistake, the spectacle was bizarre, though. With no live audience, every shout of advice or encouragement from the corners of the fighters could be heard, while some of the 22 fighters on the card saluted an imaginary audience on the way to the combat arena in an attempt to produce a little fun from sadness. It was so eerily quiet, in fact, heavyweight Greg Hardy later claimed to have acted on the advice of commentator Daniel Cormier, a fellow UFC heavyweight, was inadvertently giving to him from Octagonside, to secure victory over Yorgan De Castro.

As well as the lack of noise, and the awkwardness this presented, there were contradictions regarding social distancing. Some in attendance wore masks and gloves, while several others were seemingly exempt from the mandate. (Referees, the ring announcer Bruce Buffer, other officials inside the octagon and the ring card girl were unmasked.) However, it’s worth nothing, too, that between bouts, the cage floor was disinfected, and the padded sections were cleaned.

In the end, despite the unavoidable strangeness of it all, the one thing that remained consistent was the quality. Top to bottom, every fighter at UFC 249 fought as if the drought had been two years, not two months, and that this get-together in Jacksonville would be the last time they would ever have a chance to throw strikes at each other in an Octagon.

The main event between Justin Gaethje and Tony Ferguson was every bit as chaotic and compelling as we had anticipated going in, and it also announced a new threat to UFC lightweight champion Khabib Nurmagomedov, while UFC bantamweight champion Henry Cejudo conquered former two-time champion Dominick Cruz ahead of announcing his retirement from the sport.

We discovered as well that Francis Ngannou is still the scariest heavyweight puncher on the planet and that an enforced lockdown has done nothing to change that fact. [Poor Jairzinho Rozenstruik was the target on which Ngannou, the number two-ranked heavyweight, took out all his – and our – recent frustrations. It took just 20 seconds.]

Ask the fighters and, for the most part, they will tell you they are happy the UFC took the risk and got things moving again. If nothing else, it means they are back in work and have something to both train for and look forward to. It offers them movement again in a time of stillness.

Furthermore, given the shrinking nature of the world, and the fact that most professional sports are on enforced hiatus, there is a real sense that the UFC and its fighters are enjoying a greater spotlight than ever right now, particularly given the back-to-back, momentum-building nature of their cards.

Naturally, boxing fans starved of action in their favorite sport have recently expressed a far greater interest in MMA than they would if other fight sports were available, and one could even go further and suggest sports fans in general, the ones who just simply love the idea of competition, be it team or one-on-one, have used the UFC coming back as a much-needed shot in the arm. It might not be ideal for them – the sport, the timing of it – but it is something. And something, in a time of nothing, can mean a lot.

Be that as it may, not every fighter is in a rush to get back to competition in this time of uncertainty. Stipe Miocic, for example, the UFC heavyweight champion and part-time firefighter, has insisted he will not return until the coronavirus spread is under control, though, admittedly, one wonders how much of Miocic’s stance is fuelled by the fact he is currently nursing an injury. “I want to fight DC [Daniel Cormier],” said Miocic. “It’s going to happen, period. I’m going to give my fans what they want to see. My management has been working on dates with UFC. Right now, I’m doing what the Governor DeWine is advising and am working as a first responder. I can’t control a global pandemic.”

Suffice it to say, Dana White didn’t necessarily agree with this point of view. “I saw a quote from Stipe recently where Stipe said, ‘There’s bigger things going on in the world right now, fighting will be there forever.’ But it’s not true,” White told UFC Unfiltered. “Fighting will not be here forever. When you’re a professional athlete, your window of opportunity is very small. So, hopefully we can get Stipe back in there soon with Cormier and get the heavyweight division rolling.”

Talking of getting things rolling, there is now a sense the other players in combat sports, the ones so far observing the UFC, will feel emboldened by what the UFC achieved with UFC 249 and begin making plans of their own. Having watched, from a safe distance, the UFC venture out into uncertain waters and make it back intact, other promotions in mixed martial arts and also in boxing will likely follow the UFC’s lead, and use the UFC template, in the coming months.

Already there has been talk of UK boxing promoter Eddie Hearn staging fights in the back garden of the Matchroom Boxing mansion in Brentwood, Essex, which, should this go ahead, won’t be called Fight Island but Fight Camp, close enough for the inspiration behind it to be heard loud and clear.

Bob Arum, meanwhile, one of the main players in American boxing, has earmarked June 9 as the date he would like to get his Top Rank operation going again in Las Vegas. Arum, by the way, called the UFC’s decision to go ahead with UFC 249 in spite of the backlash “cowboy behavior”.

He wasn’t alone in his condemnation. Plenty of others underestimated the UFC when it came to their handling of an event in a time when the emphasis is on staying home. As if picturing the UFC of old, not the UFC of today, they imagined rules broken, loopholes exploited, and safety overlooked in favour of shirtless Neanderthals in small shorts and smaller gloves wading into each other for the pleasure of bloodthirsty fans stuck at home. They had visions of blood and spit spraying everywhere and nobody knowing what the ramifications of the carnage would be until all the fighters were patched up and carted off to hospital.

But they were wrong. The truth is, the UFC can these days stand shoulder to shoulder with almost all professional sports organizations and has, based on its longevity and recent form, earned the benefit of any doubt. No longer the unruly bastard child of the sports world, the UFC has grown up and has as much to lose as anyone, and it was surely always going to ensure it had the requisite measures in place before going to the extreme of asking human beings to fight inside a cage in a time of a global pandemic.

And so it proved.

It was a stripped-back operation, a desolate scene, yet it was sensible. There was clear method to the way it was run and, most important of all, it worked. The fights took place. The fighters got paid. Fans, meanwhile, if only for a matter of hours, were once again back to living vicariously through some of their favorite fighters and heroes and just for a time, forgetting about the strains and troubles of their own situations. It brought back normality in ‘the new normal’.

What they witnessed at UFC 249 wasn’t bravery to rank alongside the bravery of frontline workers and key workers keeping civilization going at this worrying time, but it was something like the sporting and entertainment equivalent of that. It offered a snapshot of working men and women breaking quarantine, leaving their families, and going out to make a living the only way they know how: by fighting.

In that respect, amid the silence of an empty arena we witnessed a microcosm of the battle so many of us are unfortunately facing right now. For whether inside or outside, whether jobless or working in the most hazardous of environments, it’s a fight. Every day it’s a fight. And part of the beauty of MMA has always been the appeal of watching others fight, an act that is both a trigger for us to carry on and do the same and for us to forget all about fights of our own.

Whatever your stance on the UFC comeback, these men and women, these fighters, are first and foremost fighting for themselves and their loved ones but are no doubt fighting for us, too – more so now than ever before.

They offer both action and hope. Hope for a better tomorrow.

...