Issue 095

December 2012

Saul Soliz, ‘The Huntington Beach Bad Boy’s longtime coach, is more pivotal in the story of MMA than you may realize

For being Tito Ortiz’s head coach for nearly 10 years, 46-year-old Saul Soliz has Jeremy Horn to thank. If the much-respected MMA journeyman hadn’t caught Soliz in a triangle choke in 1998, Saul might never have mixed his and his students’ martial arts.

LEADING MAN

SAUL SOLIZ

Longtime head coach to Tito Ortiz

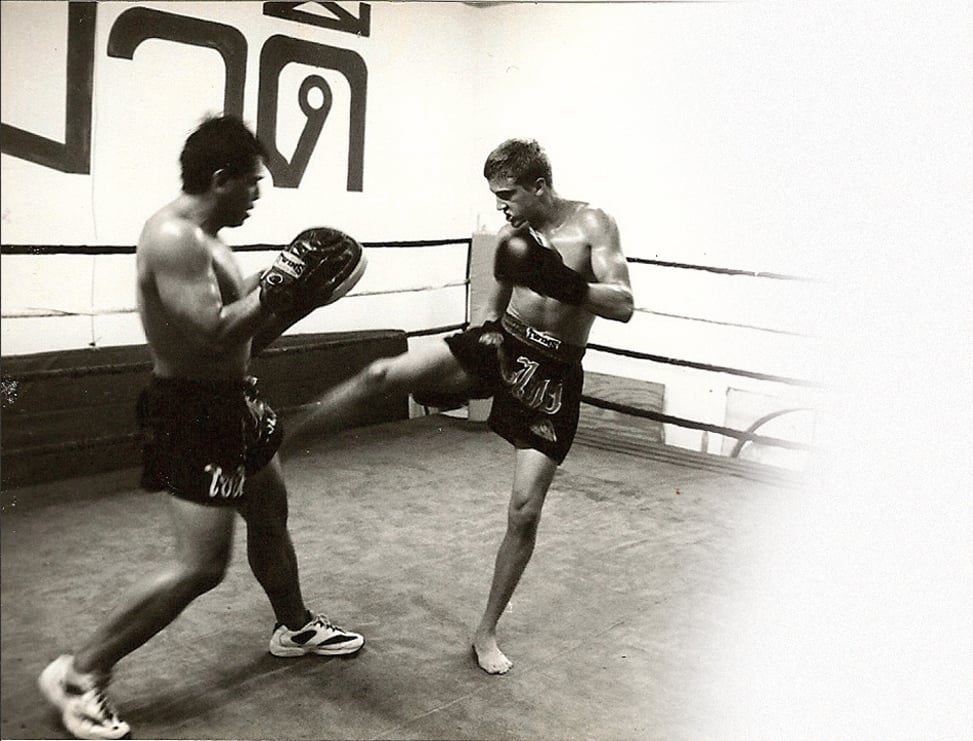

“He actually set me on the course for the success I’ve had now. Because I would box for two hours a day, I would do jiu-jitsu for two hours a day and I never combined them both, so my cardio suffered,” recalls Soliz, then a kickboxer for 14 years and a grappler for two, as well as being an instructor at his Texas gym, Patumwadee Kai USA.

“I fought Jeremy for about 10 minutes. He kept taking me down, taking me down, he got me exhausted and he got me in a triangle. After that I came back, shut down the Thai gym, and trained MMA. We sparred every day for MMA: punches, kicks and takedowns. I took a pair of boxing gloves, cut the fingers off and I made everybody in my gym do the same. All we did was cardio and we sparred. The best thing for MMA, was MMA.”

Saul’s kickboxing skills and that new training regimen at his gym in Houston – which involved today’s in-vogue, low-cost conditioning of tire drags, resistance bands and plyometrics simply due to a lack of funds – caught the eye of a promising Yves Edwards in 1999, a pre-Pride Ricco Rodriguez in 2000 and, in 2003, UFC light heavyweight champion Tito Ortiz. Names like Mark Coleman, Kevin Randleman, Mark Kerr, Pete Spratt and a young Quinton ‘Rampage’ Jackson, too, were either clients or regular visitors at Saul’s in those early years.

“We were initially the first Jackson’s, if you want to call it that,” says Saul, referring to Greg Jackson’s New Mexico MMA power plant at least partially responsible for UFC champions like Georges St Pierre and Jon Jones. “We had all the major guys here at that time. They were all on top of their game.”

The coaching skills those future legends were benefitting from, namely Saul’s stand-up tuition, were first forged in 1984 when, at 17 years old, the Dallas teen stepped into the gym of Chai Sirisuite – tutor to Bruce Lee apprentice Dan Inosanto, and the champion credited with bringing Muay Thai to the US.

In 1996, after relocating to Houston four years earlier and opening his own gym in 1995, Saul, by now a pro kickboxer, got his first taste of MMA. “When I watched the UFC I knew that was what I wanted to do, I knew I wanted to do mixed martial arts.” He began Brazilian jiu-jitsu lessons in earnest and threw himself into the unsanctioned world of underground no holds barred fighting. It was here he would battle Jeremy Horn (22lb heavier and months away from challenging for Frank Shamrock’s UFC light heavyweight belt at UFC 17) and a man named Keith Dorch whose heel hook, and Soliz’s reluctance to tap, would break Saul’s tibia and fibia and in-turn ultimately end his MMA career.

His time as a competitor was over, but his years as a coach and promoter were about to blossom. In 2000, after convincing the Texas boxing commission to allow MMA, Soliz started Renegades Extreme Fighting, the Texas-circuiting promotion that would run for 10 years. “I actually had John Ouano, who was the original manufacturer of the UFC gloves, make me a special eight-ounce glove for the Texas boxing commission so we could start MMA here. I was the first promoter to do MMA, I was the first promoter to do MMA in a cage, I was the first promoter to do amateur MMA.” And he even lead Ricco Rodriguez to UFC heavyweight gold in 2002.

From his role as coach to Ortiz in one form or another from 2004 up until 2011 (including the final 2012 fight camp of ‘The People’s Champ’), Soliz, now 46 and owner of Metro Fight Club in Houston, has a favorite Ortiz memory. “The 2004 fight he had with Vitor Belfort,” states Soliz. “His back was against the wall just like it was with Ryan Bader, but at that time I don’t think he had the options he had when he fought Bader. It was do or die.

“He had to beat Belfort… That was the first time I trained him for a complete camp. I was amazed at how much work he would do. How much he was willing to sacrifice for his goals. In the past, I think everyone felt the same way I did: he was the ‘Huntington Beach Bad Boy.’ I think those championships came easy and he didn’t have to dig deep. And I think that fight was one of his more impressive moments where he had to actually dig deep. His back was against the wall, and he did it.”

...