Issue 090

July 2012

How the Gracies, mixed martial arts’ first family, first met their match via Japanese geometry.

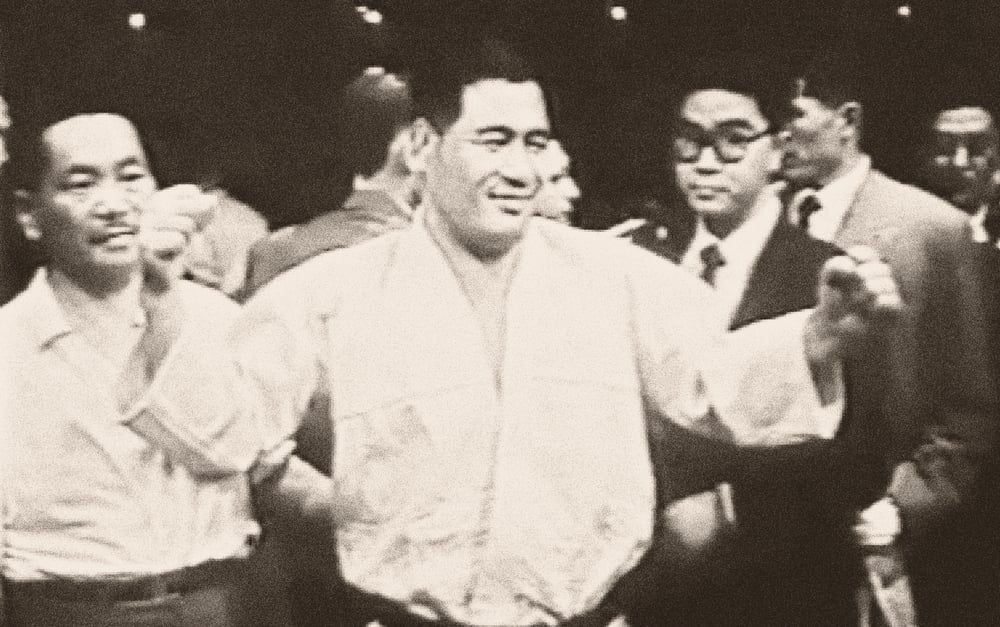

October 23rd 1951. A reported 20,000 spectators packed a Rio soccer stadium to watch ‘The World Championship of Jiu-Jitsu’, billed as a long-awaited grudge match between a Brazilian legend and a foreigner – Gracie jiu-jitsu co-founder Helio Gracie and famed, feared judo player Masahiko Kimura.

Brazilian jiu-jitsu was developed by the Gracie family. Without the Gracies, there would be no Ultimate Fighting Championship (Rorion Gracie co-founded the promotion) and no mixed martial arts (their ‘Gracie Challenge’ saw some of the first-ever style-versus-style matchups). They revolutionized the way we think about fighting.

After years of private tuition from the Japanese judoka Mitsuyo Maeda, the weird clan of doctor’s kids came to the conclusion that, eventually, every fight ends up on the floor. Building on their judo foundations, they devised the ultimate ground fighting system.

The key player was Helio, the runt of the litter who was the smallest and often sick. He perfected a set of chokes and joint manipulations that enabled a small, weaker man to beat a larger adversary. Brains beats brawn. Helio achieved celebrity in Brazil, taking on all comers, and threw out a challenge to heavyweight boxing champ Joe Louis: a no rules fight, one million dollars, winner takes all. The ‘Brown Bomber’ never got back to him. His son Rorion later used similar tactics to promote the family art and his ‘Gracie Challenge’ publicity stunt indirectly led to the creation of the UFC.

Over the years, Helio had defeated a number of judo players. Eventually, he called out Masahiko Kimura, a seventh dan, 16-time Japanese champ with experience of pro wrestling. Kimura, who was four years younger than the 39-year-old Helio and outweighed him by 80lb, dismissed the impertinent challenge.

Instead, he sent along fifth dan Yukio Kato to slap down the yapping Brazilian. The first fight ended in a draw. In the rematch, Gracie choked Kato unconscious. Kimura was left with no choice. He had to step up.

Interest in the contest reached fever pitch. The only venue that could accommodate the thousands who wanted to attend was the enormous Maracana Stadium in Rio de Janeiro. It was the talk of the nation. Even the President of Brazil turned out to see the showdown.

As with his fight against Kato, Gracie insisted on rules that favored him: the fight was set for two 10-minute rounds and could only be ended by a submission. Kimura was unconcerned, telling the press that Gracie should be considered the winner if he could last over three minutes. The needle went both ways.

In his biography, Kimura recalls the reception he received on the day of the fight: “When I entered the stadium, I found a coffin. I asked what it was. I was told, ‘This is for Kimura. Helio brought this in.’ It was so funny that I almost burst into laughter. As I approached the ring, raw eggs were thrown at me.”

Once the fight got under way, Kimura took control; tossing Gracie around the ring like a rag doll. It has since been suggested that he was trying to circumvent the rules by trying to dump the older man on his head and knock him out. The reportedly luxuriously padded canvas prevented this from happening, but the relentless pounding weakened the Brazilian superstar.

Only 13 minutes into the action, Kimura caught Helio in a shoulder lock known to judokas, but not the Gracies, as a reverse ude garami. Controlling Gracie’s left wrist with a figure-four, the judo champion ruthlessly twisted Gracie’s arm behind the Brazilian’s back, and by his recollection twice heard bone breaking. Gracie resolutely refused to surrender, but his corner had seen enough.

Carlos Gracie threw in the towel to save his little brother. Ever since that day, the hold that secured the win has been commonly known to grapplers as the kimura.

Years later, Helio told people he always knew he would lose the fight because of the huge size advantage Kimura held over him. Gracie claimed he pushed for the fight because Kimura was the best in the world and he wanted to fight him to test himself as a martial artist. He was curious to see if he the judoka could come up with anything that would surprise him. Some see this as an admirable attitude. Others reject the comments as a lame attempt to claim a moral victory from a solid defeat.

There are echoes of the fight in the modern era of mixed martial arts. By 1999, the Gracie family had an aura of invincibility. To MMA fans, the Brazilian clan was superhuman, always capable of finding a way to win. Then along came a Japanese superstar – Kazushi Sakuraba.

First to fall was Royler Gracie at Pride 8 by kimura. Taking no chances, they sent over undefeated superstar Royce and demanded special rules, including no time limits and taking away the referee’s right to stop a contest. Sakuraba’s wrestling skills nullified Royce’s takedown attempts and his leg kicks began to take their toll. After 90 grueling minutes, Rorian threw in the towel to save his younger brother and ‘The Gracie Hunter’ had claimed another victim.

Renzo and Ryan also made the trip to Japan and lost, by kimura and decision respectively. Again the first family of jiu-jitsu had met their match in the shape of a Japanese warrior, and the kimura remains an effective weapon to this very day.

...