Issue 093

October 2012

With the UFC planning an expedition to Africa’s southern tip, Fighters Only charts virtually unexplored MMA territory.

When UFC president Dana White began briefing media at the UFC 150 press conference in June, few could have imagined he would reveal the UFC’s next target in its ever-expanding push for global domination would be the country at the southernmost tip of Africa.

“Mixed martial arts is huge in South Africa right now,” White stated to the media scrum in Denver, Colorado. “There’s a show down there now that I just heard about that is doing 1.2 million viewers every time it’s on. So the sport is booming all over the world, and yeah, South Africa is next. That’s where we’re going.”

The show White was referring to was EFC Africa, the continent’s leading MMA promotion, based in Johannesburg. Its first event, in November 2009, drew a crowd of just over 3,000. Now, just two and a half years and 14 events later, it regularly hits a peak audience of over one million viewers via live television broadcast in South Africa, and that doesn’t include the number of viewers tuning in from other African nations either.

Mixed martial arts in Africa has come a long way in a short space of time, but the early pioneers of the sport have labored for over a decade to help the game reach this point. One such pioneer, dubbed the ‘Father of South African MMA,’ is Rodney King, whose introduction to mixed martial arts came in 1997 when he met a few Americans adding strikes to BJJ. Intrigued, King began incorporating MMA into his Muay Thai classes back in Johannesburg.

“A lot of it was trial and error and the school of hard knocks,” King recalls to FO. “Back in the ‘90s, especially in South Africa, martial arts were taught separately, so when we started integrating stand-up, clinch and ground we were seen as outcasts. The traditional schools didn’t appreciate us in their neighborhood and everyone thought we were bloodthirsty, angry young men. Maybe they were right; we did attract a lot of bouncers and guys who had a reputation on the street, or at least wanted one.”

According to King, his first events were challenge matches at his dojo, South African Gracie style, for anyone who wanted to test themselves against his students. From there, events progressed to bigger venues but ultimately proved unprofitable. “Attendance was low because people didn’t understand MMA,” he recalls. “Hardly anyone was doing BJJ so no one liked it when the fights went to the ground.”

In November 2001, Wiehahn Lesch, a 27-year-old policeman from Cape Town, made the 870-mile trip up to Johannesburg to compete at King’s Pride and Honour MMA event at Carnival City, the same venue where Hasim Rahman knocked out Lennox Lewis in a historic boxing bout just a few months earlier. As Lesch entered the cage, all he knew about his opponent was that he was from America and his name was Forrest Griffin.

“At that time I hadn’t even been in MMA a year yet,” says Lesch. “I was confident because of my background as a national wrestling champion but, looking back, that confidence was stupid because I knew so little about MMA. Taking Griffin down was easy and ground ‘n’ pounding him was easy too. Unfortunately, I had virtually no idea how to defend chokes so he eventually got me with a rear naked and I had to tap.”

The November 2001 matchup was only Griffin’s second professional fight, long before his groundbreaking Ultimate Fighter finale slugfest with Stephan Bonnar. Griffin would go on to become UFC light heavyweight champion and one of MMA’s greatest icons. Lesch, on the other hand, went on to build a record of 19-7, work in South Africa’s National Intelligence Agency, and then eventually settle down to livestock farming.

“Forrest told me he’d never been taken down that easily and said he’d return to America and spread the word that SA boys can fight. I was proud of that, but realized how much I had to learn.” Like Griffin, Lesch is still active in MMA. At the age of 38 he is training hard in his free time and hopes to compete again before the year is out.

In the early 2000s, on the other side of South Africa in Cape Town, interest in MMA was starting to develop thanks to brothers Mike and Omar Mouneimne, who had set up Pride Fighting Academy in 2002 and started African Pride Fighting Championship events in 2003. Like King, the Mouneimne brothers started holding events to prove MMA superior to traditional martial arts.

“Our first event had ticket queues stretching around the venue and attendance of over 1,500,” says Mike. “There were submissions and a couple of vicious KOs but the crowd went mad when a guy got picked up and slammed so hard that it shook the roof.”

APFC put on 18 events from 2003 to 2008 and offered up to R15,000 (USD$1,800) for a win. At one event in February 2005, Cape Town’s Rico Hattingh, a renowned grappler and APFC heavyweight champion, was given the opportunity to defend his title against Trevor Prangley, a South African who had relocated to America and had just won his first UFC bout.

“I was on a five-fight winning streak and very confident I could beat Trevor,” Hattingh recalls. In round one Prangley caught Hattingh with an elbow under the eye. The wound swelled and bled but Hattingh fought on and, with just 20 seconds left on the clock in round three, cinched up a reverse triangle.

“Up until that point, Trevor had never tapped in a fight and, as far as I know, a reverse triangle had not been seen as a finish in UFC or Pride. Trevor’s cornerman, former Strikeforce champion Josh Thomson, even congratulated me on that.”

When Prangley returned to the US and defeated Matt Horwich the very next month, Hattingh became a blip on the international MMA radar and was invited to train with Team Quest in Oregon and California, with the likes of Randy Couture and Dan Henderson. Hattingh fought in the US twice, losing both times, but was still ranked as South Africa’s top heavyweight until a back injury stopped him competing in 2011. He holds a record of 14-2 and remains undefeated on home soil.

Although Prangley lost to Hattingh in 2005, he went on to become Africa’s most internationally accomplished mixed martial artist, fighting for UFC, Strikeforce and Bellator, amongst others. Prangley left South Africa in 1997, at the age of 24, to further his wrestling dreams. He settled in Idaho, USA, and began jiu-jitsu during the college wrestling off-season. He achieved the rank of NCAA Division I wrestler then turned to pro-MMA in 2001. After a string of victories, he made his UFC debut at UFC 48, where he fought Curtis Stout and won in round two via neck crank.

“I got my first UFC fight on 10 days’ notice because someone got injured,” Prangley says. “I was out of shape but realized the opportunity may never come again. I won, and that win was what really started my whole career.”

So far, Prangley has put together a record of 41-11 and 1 draw and has held the titles of BodogFight middleweight champion, Shark Fights light heavyweight champion and MFC light heavyweight champion. Prangley now runs an American Kickboxing Academy gym in Idaho and has two more fights scheduled for 2012. With the recent boom in South African MMA, he has even expressed interest in another sub-Saharan bout.

“I think the explosion in MMA is great! By nature, South Africans are tough and I think the sport’s growing popularity will eventually produce more fighters who, like me, can do very well on the international circuit,” Prangley adds.

Other South African fighters who have had success internationally include Neil ‘Goliath’ Grove, Mark Robinson and Xavier ‘X-Man’ Lucas. Grove resides in England and made his UFC debut at UFC 95 in 2008 where he lost by heel hook submission. Robinson, a two-time world sumo wrestling champion and 2001 ADCC submission wrestling champion, took on Bobby Hoffman at UFC 30 but had his UFC prospects put to bed with a solid KO elbow. Though the result was later changed to a no contest when Hoffman failed a drug test. Lucas, a former South African Special Forces policeman, moved to Australia in 2006, then captured the Pan Pacific Shooto middleweight title as well as the Xtreme MMA world middleweight title. He is still active on the Australian and Pacific MMA circuits.

The force behind African MMA

While Africa has produced athletes with the potential to be successful on the world stage, elite mixed martial artists have always had to emigrate to pursue their MMA dreams… until now. When EFC Africa burst onto the African MMA scene in Johannesburg towards the end of 2009, it quickly differentiated itself from the competition thanks to ambition and professionalism.

According to EFC Africa president Cairo Howarth, the promotion came about due to his frustration with the massive discrepancy in quality between local and international MMA. “As an MMA student and fan of the UFC, I became frustrated with local MMA because there was nothing for local athletes to aspire to. It got to a point where we wanted to start an MMA promotion so that South Africans, and later the rest of Africa, would have an event worth fighting for.”

With a background in television and staging live events, Howarth was able to put together a high-quality show that was a hit from day one. He adds: “We watched international promotions very closely and took elements that would work in Africa. A challenge that we’ve faced is Africa’s lack of pay-per-view television, so we’ve had to change our business model and distribution accordingly.”

EFC Africa commenced broadcasting on e.tv, Africa’s largest English-language TV channel, from that first card with three tape-delayed broadcasts. EFC’s first live broadcast took place on March 2nd this year, with four bouts from EFC Africa 12 aired live in 49 countries on e.tv. Millions of first-time MMA viewers got to see Jeremy ‘Pitbull’ Smith dethrone Garreth ‘Soldierboy’ McLellan to become EFC Africa’s undisputed middleweight champion.

TV ratings revealed that the event clocked a peak audience of over 1.6 million in South Africa alone, and pulled 25.9% of the total available South African TV audience. When compared to other local televised sporting events, EFC Africa 12 pulled a peak audience 70 times greater than that of boxing and significantly outperformed mainstream African sports such as rugby and cricket.

EFC Africa is also the only sporting property on the continent that broadcasts live to cinemas (23 cinema complexes across South Africa) as well as live online across the globe. According to Howarth, online pay-per-view buys are growing at a rate of around 50% show-to-show, with over half coming from outside Africa.

“Outside of our show, MMA is largely unknown on the continent. We own the market, but we are also responsible for building an entire sport as we go along. The UFC has had no presence in Africa so we had to educate the fans, media, potential athletes and everyone else. We even implemented our own anti-doping policies and procedures.”

As EFC Africa has grown, it has been able to increase fight purses, driving up the level of competition between athletes who wish to reap the rewards of victory. Top competitors have been known to earn up to R100,000 (USD$12,200) per bout. Currently, EFC Africa produces around eight MMA events a year, all hosted on the African continent, and has over 100 MMA athletes exclusively contracted from across Africa.

“We are planning on becoming the second most watched sport in Africa, just behind soccer,” Howarth adds. “And one of the few African sporting properties with a global broadcast reach and worldwide fan following. With over a billion people, Africa has greatly untapped talent and huge potential. With our vast TV reach, quality product and rapidly growing fan base, we produce some of the best MMA athletes in the world.”

Traditional fighting styles

If Africa is where humans took their first steps, then surely it is where they threw their first punches. Various forms of hand-to-hand combat have developed across the continent, resulting in formidable fighting athletes that may eventually cross over to mixed martial arts. Three such examples include:

Musangwe

Each December in Venda, Limpopo province in South Africa, hundreds of men and boys gather for musangwe, a traditional fist-fighting festival. According to legend, the sport was born from the restlessness of Venda farmers in the late 1800s. Today, the bareknuckle spectacle attracts thousands of spectators who cheer on local heroes as they do battle under the sweltering summer sun. Contestants range from children to senior citizens and fight until scoring a knockout or submission. Fighters compete for pride and esteem, not money. A few musangwe fighters have already shown interest in competing inside the cage.

Dambe

The West African combat sport known as dambe originated as a harvest festival pastime. It resembles boxing, although one hand is used to defend and one to strike. The striking fist is known as the spear and is wrapped in cloth and cord. The defending hand is known as the shield and is left bare, to block and parry attacks. Dambe is said to have once incorporated wrestling, known as kokawa, but this has fallen out of fashion. The objective is to knock down an opponent using the offensive hand.

Senegalese wrestling

Also known as njom, lutte Sénégalaise or laamb, this martial art is a national sport in the western African country of Senegal. A cultural tradition that has grown into a lucrative sporting event, Senegalese wrestling resembles MMA in that it is a form of wrestling that allows strikes in order to force an opponent to the ground. Events are big business, with TV broadcasts and corporate sponsors. Top fighters earn thousands of dollars per fight to entertain packed stadiums.

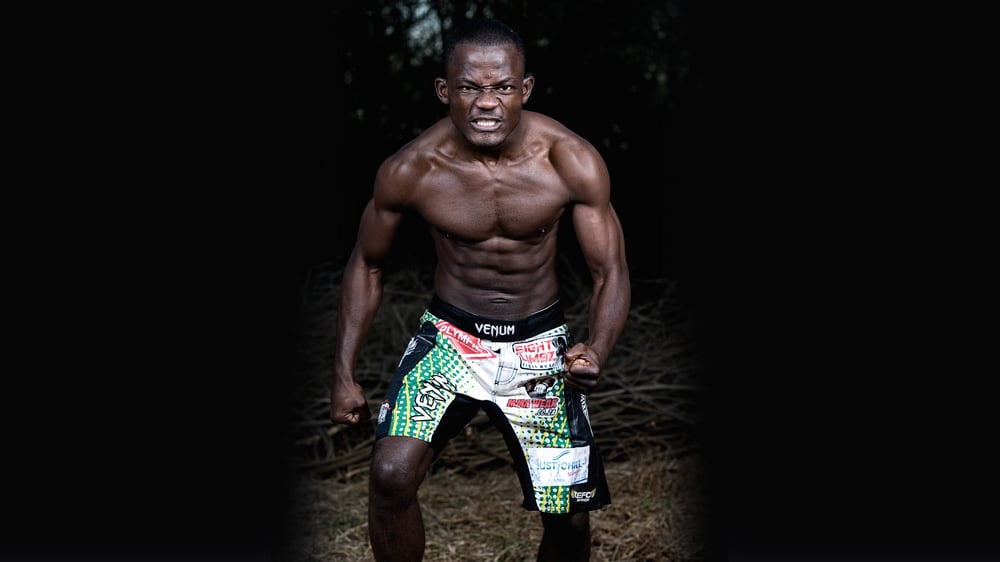

Africa's got talent

While the UFC’s current list of champions are now household names across Planet MMA, perhaps less is known about the hierarchy of champions in South Africa. Here’s a rundown on the cream of African MMA.

Ruan Potts: EFC Africa heavyweight champion

Already an accomplished South African judo champion, Potts was bitten by the MMA bug in 2008 while working in the UK as a dental technician. A visit to an MMA gym to sell mouth pieces resulted in MMA classes, and Potts began competing soon after. Potts made his EFC debut upon his return to SA, against Calven Robinson, a muscle-bound behemoth, and demolished him in just 90 seconds. He worked his way up to a title shot and defeated Norman Wessels in June 2011 to claim the EFC heavyweight title. He has defended it once and brought his record to 14-0. In June 2012, Potts traveled to Las Vegas to train with top international fighters (including Cheick Kongo and Kevin Randleman) in order to help prepare for his next title defense later this year.

Jeremy Smith: EFC Africa middleweight champion

South Africa’s most internationally accomplished fighter that still resides in SA. So far, Smith has bested three American opponents, two of which were beaten in their own backyard. His first international opponent was Julio Gallegos, who left SA with his body battered and his record bruised. Five months later, Smith defeated Dustin Rhodes in Tampa, Florida. And he last fought internationally at XFC 13, in December 2010, again in Florida. His opponent, Joe Ray, was heralded as a bright prospect and undefeated, but lost via split decision.

“Joe was, without a doubt, my toughest opponent,” Smith tells FO. “He had been a coach at Tiger Muay Thai and had deadly elbows, punches and kicks. Ending his win streak was a real achievement because every opponent he beat he put in hospital. He even put me in hospital, and I won!” Smith captured the EFC Africa middleweight title from Garreth ‘Soldierboy’ McLellan at EFC 12 in March. His record currently reads 11-1.

Costa Ioannou: EFC Africa lightweight champion

Greek South African Costa Ioannou’s debut at EFC 3 in May 2010 turned heads when his opponent, Brendon Katz, was treated to three-rounds of sheer devastation. The bout took ‘Fight of the Night’ honors but Ioannou felt that he performed below his ability. Five months later, he took his second EFC victory via first-round submission. Then, at EFC 8 in April 2011, Ioannou secured the lightweight title by triangle choking Wentzel Nel into submission. Ioannou has defended his title twice and is now 5-0. He is seen as EFC’s most dominant champ, and a legitimate international prospect.

Demarte Pena: EFC Africa featherweight champion

Son of an Angolan rebel general, Demarte Pena grew up in the middle of a civil war. When his family moved to SA in 1998 he took up Muay Thai and gradually made his way to MMA. He took his first professional fight at EFC Africa 7 in February 2011, at just two days’ notice. Pena worked toward a featherweight title shot and became champion at just 22 years of age. His victory at EFC Africa 10 was groundbreaking for a number of reasons, as he became the promotion’s first featherweight champion and first champion born outside of South Africa. As such, he instantly became a figurehead for African MMA and sparked the hopes and dreams of aspiring warriors across the continent. Pena has defended his title once so far, at EFC 14 in June 2012, and holds a record of 4-0.

Fighters Only is global

The first issue of Fighters Only’s South African edition went on sale in December 2009, and from humble beginnings, with a distribution of only 50 retail outlets, the popularity of the magazine has skyrocketed over the last two-and-a-half years.

Issue 32 hit the shelves on July 27th and was available at over 3,000 retail points. The issue features EFC Africa lightweight champion Costa Ioannou as the cover star, and is forecasted to break the all-time record for sales. The popularity of the mixed martial artists in South Africa has grown to an extent where these guys are now fully fledged celebrities, on par with other sports stars. Springbok rugby players are constantly see with MMA fighters these days in SA social circles.

FO South Africa editor Dirk Steenekamp says: “As with everywhere else on Planet MMA, Fighters Only is at the heart of the community and the same applies here in South Africa. I’ve heard stories of people waiting for storeroom managers to get magazines out the back and put them on the shelves when readers know the new issue should be on sale. It’s kind of crazy that people are that passionate about their reading material.”