Issue 089

June 2012

A new evolution of martial arts is coming. With so many different styles yet to be added to the skill-sets of fighters, Fighters Only takes a look at the latest disciplines giving mixed martial artists the competitive edge like never before…

UFC broadcaster Joe Rogan has often declared that martial arts as a whole have progressed more since the 1993 debut of the cage-fighting promotion than at any other point in history and, the truth is, he’s probably right.

What began as an intriguing clash to determine the dominant style in martial arts ultimately forced a revolution in hand-to-hand combat. It quickly became evident that no singular martial art is a fail-safe in real-world scenarios, and for fighters to succeed, training in a multitude of both striking and grappling disciplines is the only approach.

In the early days of the sport now known as mixed martial arts, the techniques evolved in phases. It began with Gracie jiu-jitsu, when opposing fighters were ill-prepared to deal with the slithering groundwork that saw Royce Gracie submit 11 straight UFC foes. When Gracie left the UFC, unhappy with the evolution of the rule set in the Octagon, wrestlers such as Mark Coleman and Mark Kerr took center stage.

Don Frye would add boxing to the mix, and Maurice Smith brought successful kickboxing to the cage. And Frank Shamrock showed the world what raw athleticism could do in fighting. Eventually, the fighting world settled on a formula: wrestling, jiu-jitsu, boxing and Muay Thai became the key components to MMA training, and the days of fighters representing one particular style quickly fell by the wayside.

But MMA continues to evolve, even today, and both fighters and coaches are constantly looking for ways to one-up the competition. So what other arts are fighters exploring in their development as complete mixed martial artists? Fighters Only talked to a few industry figures to get their take.

Striking arts

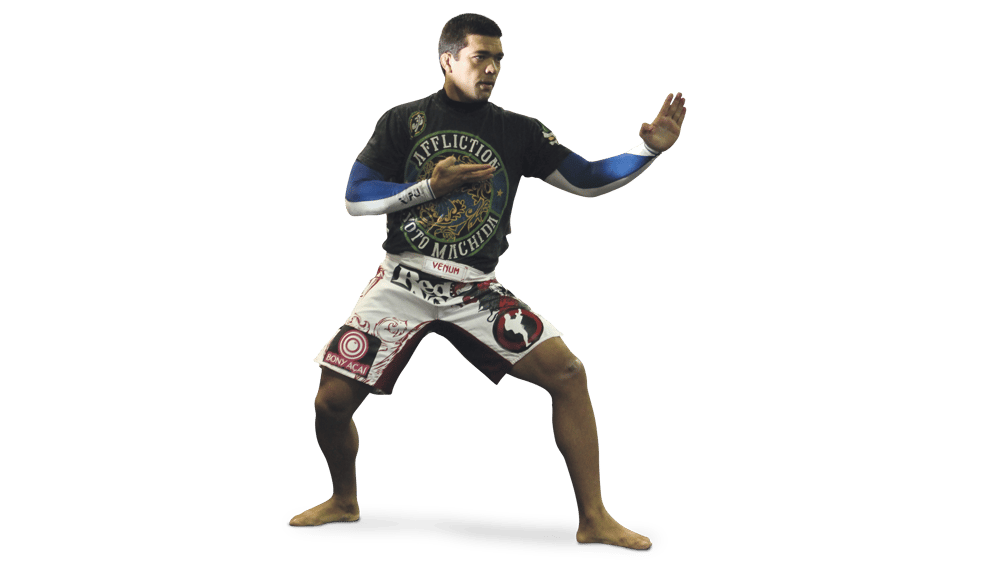

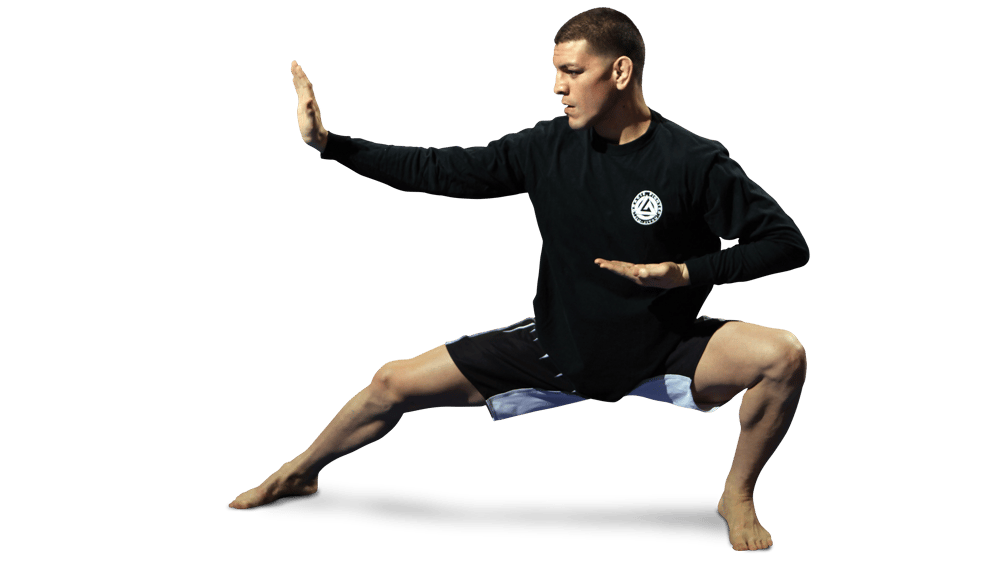

In 2011, the front kick became a fashionable striking technique. In February of that year, UFC middleweight champion Anderson Silva unleashed a furious front kick to the face of Vitor Belfort that dropped ‘The Phenom’ out for the count. In April, Lyoto Machida added a twist to the blow, flashing a kick in true Karate Kid fashion before flattening and ultimately retiring UFC Hall of Famer Randy Couture. Suddenly, fighters at all levels of the game were firing a shot up the middle, and rather than using it as a traditional kick to the body, the front kick suddenly was being fired at the chin in hopes of a knockout.

This year, Edson Barboza was responsible for the latest kicking fad when he leveled Englishman Terry Etim with a spinning wheel kick at January’s UFC 142 event. While scoring a sure ‘Knockout of the Year’ candidate and $130,000 in bonuses, Barboza also brought the potential of the spinning strike to the forefront, and many others have recently been following his example.

Barboza, who boasts a background in taekwondo, thinks scouring through the techniques of such traditional martial arts can provide a real advantage to competitors. “I started training taekwondo when I was eight years old,” Barboza tells FO, through an interpreter. “Today I am a red belt in taekwondo.

“MMA means mixed martial arts – it means taekwondo, boxing, Muay Thai, jiu-jitsu, wrestling. Every martial art is mixed inside the Octagon, no matter what. All the fighters are getting better every year, and any one detail can make the difference in the fight. So I think the fighters are looking for something different that can help them to surprise their opponents during the fight.

“That’s why we are able to watch different movements in MMA now. It’s good – good for the fighters because they are getting better and good for MMA fans, because they will be able to watch great fights.”

Muay Thai has generally been the basis for most MMA striking training due to the powerful kicks and the efficient use of both elbow and knee strikes that are hallmarks of the art. But Barboza believes traditional Eastern martial arts such as taekwondo and karate (which now serves as a blanket term for many Asian arts), not to mention China’s kung fu and its derivative, san shou, should not be dismissed.

And just as it did in the early days of the sport, Barboza believes MMA continues to prove you need more than one set of techniques and philosophies. “The techniques from taekwondo allow good leg work, and Muay Thai techniques work the power and punches,” Barboza adds. “Taekwondo techniques provide more agility and speed, and Muay Thai provides more power, so one art completes each other.”

Barboza, of course, isn’t alone in his affinity for taekwondo. Current UFC lightweight champion Benson Henderson is a black belt in the art, and high-flying firecracker Anthony Pettis also culls many of his attacks from his taekwondo base. But just as those two fighters will forever be linked together by Pettis’ incredible 2010 ‘Showtime kick’ off the WEC cage, Barboza believes the true key to striking development is variation and the element of surprise.

“Taekwondo is an amazing martial art, as are many others,” Barboza says. “MMA provides us a very large opening for new moves and techniques. That’s the magic of MMA. You never know what will happen or what martial art the fighter will apply. It is always a surprise. That is the point that the fighter should work on.”

In that spirit, Barboza, teasingly, reveals he’s already got another surprise in mind. “I have a few favorite techniques I’ve been working on, but it will be the surprise for the next fight,” he adds with a wry smile. “It’s a secret.”

Grappling

While some form of heavy bag hangs from the ceiling of almost every martial arts gym around the world, modern MMA has its roots planted firmly in the grappling arts. Royce Gracie’s awkward front kicks and slaps to the ears weren’t exactly intimidating, but it was his ability to manipulate positioning on the floor that revolutionized the combat-sports world.

Likewise, when wrestling-based attacks of Coleman and Kerr were controlling the octagon, it wasn’t because opponents were afraid to stand and trade. You were going to your back if you were facing those monsters, so you might was well just accept it.

Due in great part to these early UFC legends, both jiu-jitsu and wrestling have become staples in MMA training. Neither appears to be going away anytime soon. But if a fighter hopes to add a new set of skills to his or her arsenal, where is best to look? For Strikeforce female bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey, that’s an easy answer.

“The Olympic sport of judo isn’t judo,” Rousey says. “It’s judo in sport form, but it’s not a martial art. Judo is a martial art, and there’s a whole philosophy behind it.

“One of the main philosophies behind judo is maximum efficiency and minimal effort. So when you see a double-leg, which you see all the time, you would say, ‘Oh, that’s a wrestling move,’ but in judo it’s called a morote gari. I figure that if the way that you do a technique is the most efficient way you can do it and uses the least amount of energy possible, that is judo.”

When most people conjure up images of judo, it involves gi-encased athletes violently hip-tossing opponents to the mat in a dizzying blend of acrobatic warfare. But Rousey, perhaps more than any male or female fighter in MMA history, has proven the effectiveness of the art in terms of not only takedowns but also submissions. An Olympic medalist, Rousey has eight total professional and amateur MMA fights. All eight have ended via first-round armbar.

And the new Strikeforce champion believes the art she’s trained in since childhood is a perfect compliment to fighters of all sizes and skill-sets. “That’s the really cool thing about judo,” she says. “There’s no particular body type that will make you better at it.

“There’s so many styles of fighting that if you’re super tall and skinny and someone else is kind of super short and stocky, you guys wouldn’t do the same judo technique, but you could both be very good at judo. That’s how you see a lot of these really cool, conflicting styles.”

It’s for these reasons Rousey’s game has developed so quickly and why she believes the roots of true judo (which also gave birth to its Russian off-shoot, sambo) are valuable for fighters looking to gain an edge. However, she stresses the importance of learning the martial art of judo over the sport version of the art.

“Not every style of judo works for MMA,” Rousey says. “If you’re an Olympic gold medalist in judo like Satoshi Ishii is, you would assume you would do better than Karo Parisyan, who never competed that much internationally. But it’s the style.

“The way that Ishii does judo requires a gi and he gives up position the way that he lands, and they don’t really spend that much time on submissions, traditionally, in the Japanese style. That’s why I think even though he was more accomplished in the sport of judo, he didn’t do that well in MMA. The reason why some judo players do awesome and some fall off is because of that style conflict. I think more of the European, the Cuban and the Brazilian judo players are the ones we’re going to be looking to get more of.”

The next evolution

So perhaps as a direct result of MMA, many martial arts are no longer being taught in a traditional manner. The ‘mixed’ part of the sport has proven to everyone willing enough to take an honest look in the mirror that techniques need to be culled from various arts in order to be successful in the cage.

Jason Mertlich, who has trained in multiple disciplines since he was a teenager and is now an instructor at The Pit Elevated, believes things are evolving so quickly that within a decade, fighters will likely no longer need a classification.

“For maybe the next five years you might see a little bit of super-high-level wrestlers coming in and doing really well or super-high-level kickboxers,” Mertlich says. “But I think in maybe a decade from now, we’ll stop talking about, ‘This guy is a wrestler. This guy is a kickboxer.’ I believe Jon Jones has kind of shown us what can happen when you get a high-level athlete that’s good at a lot of different things, and athletic kids like Jon Jones are going to be coming into the sport, and it’s just going to raise the bar.”

If there is a need for a new martial art influence, Mertlich said it would involve strategies for fighting in close proximity to a cage wall. It’s here – the spot where Randy Couture made a career of using his Greco-Roman wrestling clinch and ‘dirty boxing’ – where Mertlich sees the biggest opportunity for growth in the sport.

“It’s just melding the arts all together, and I really think the future of the sport is developing techniques that work against the cage,” Mertlich says. “From my personal view, 90% of the fights are won or lost against the fence.

“Guys have a boxing coach, a Muay Thai coach, a wrestling coach and a jiu-jitsu coach. Now you’re having to take these different things, and once you have a basic understanding of all of them, you have to adapt them to the sport of MMA because most wrestling now takes place against the fence. It doesn’t take place on an open mat in a circle like a wrestling competition.”

So as MMA continues its rapid global expansion, the sport is sure to gain some traction in areas known for a particular style of homegrown fighting. From the Korean arts of hapkido and the infamous all-round art kuk sool won, Laos’ muay lao, Israel’s krav maga, Indonesia’s silat variations (see the recently-released feature film The Raid: Redemption for a some heart-racing Hollywood examples), and more, there are various forms of martial arts in all cultures. However, with nearly 20 years of modern-era MMA and tens of thousands of fights to observe, Mertlich believes the discovery stage of the sport is over. Now is time for refinement and invention.

“It’s just the mind-set of keeping an open mind and realizing none of us know everything,” Mertlich adds. “We’ve got to collectively keep evolving the sport to evolve as martial artists. We have to look at what our surroundings are, what tools are available to us and then adapt our techniques or innovate techniques that are more efficient. Obviously we don’t need to be fancier. We just need to be more efficient in getting the job done, whether it’s against the fence or not.

“There are lessons to be learned from the past and from the current situation, and then people are innovating and developing things now. There are areas that need to be explored further, but I don’t think there’s anything secret out there that’s not available to everyone.”

Useless techniques

While the development of martial arts has seen the incorporation of techniques from across all families of martial arts, it also rendered loads of techniques as relatively useless. Gone (thankfully) is the idea of some ‘death touch’ ending a fight – or a life. And while the artful animal styles of some kung fu teachers is better left to Hollywood than the Octagon, UFC lightweight striker Edson Barboza said the key to developing as a fighter is the ability to pick out what does and doesn’t work and then incorporating that into a game plan.

“Any technique may be used in MMA,” Barboza says. “It is mixed martial arts, which means everything may be used coming from any martial art, no matter what.”

Take something beautiful like capoeira, for instance, the famed acrobat art of Barboza’s Brazilian homeland. The early days of vale tudo proved that capoeira disciples were vastly ill-prepared to deal with elite grapplers, both wrestlers and jiu-jitsu players, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a reason to work some of the art’s traditional ginga movements into a training routine.

Barboza adds: “I don’t think there are really any techniques that absolutely won’t work in the Octagon, and that’s why MMA is so fantastic.”

Wrestling vs. judo

Even though the UFC was designed to pit martial arts forms against one another to determine the superior approach, it largely gave birth to its own form of fighting: MMA. But one rivalry has continued past the initial style vs style debate – wrestling vs judo.

Strikeforce female bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey believes the debate is completely unwarranted. Instead, the lifelong judoka said the two should likely be viewed as interchangeable strategies, neither of which could or should be considered superior.

“I see judo being done in wrestling all the time,” Rousey said. “It’s just that we don’t call it judo. Every single time you do a technique, and it happened with little muscle, then it was a judo technique. Any time you do a double-leg in wrestling that was timed correctly, I consider that judo because it was maximum efficiency with using as little effort as possible.

“I also see wrestling in judo all the time. I’ll see someone go for a technique, and they don’t time it right, but through sheer athleticism they will it through. I consider that wrestling. So I don’t think one is better than the other. I just consider them being entirely interchangeable. If I had to muscle through, then I consider that wrestling. If it happened easy, then I consider that judo.”

Consistent vs. unique

With the growth of MMA, The Pit Elevated coach Jason Mertlich said he’s seen a marked change in how traditional martial arts are being trained. The coach said most of the students he sees are no longer interested in learning disciplines such as jiu-jitsu in their original forms but rather with focus on the techniques that are most applicable for MMA.

“I think a big thing now is that 90% of the people that come to my jiu-jitsu class, they want to train no-gi, and they want it more suited for that type of environment,” Mertlich says. “In the past, it’s been people seeking out gi jiu-jitsu, the Gracie gyms and things like that, whereas now people just want to get in and learn what they’re seeing on Saturday night in the UFC.”

While some high-level fighters take a more traditional approach to the individual arts, many MMA competitors also train with homogenized looks at the key components of mixed martial arts. As such, Mertlich said taking a unique approach to the sport such as the judo of Ronda Rousey or the point-karate approach of Stephen Thompson can earn you positive results.

“Obviously, it’s hard to train for an Olympic-level judo athlete,” Mertlich says. “There’s not a ton of them lying around at your disposal – or world-class karate guys. You get a lot of tough MMA guys that can kind of mimic that look, but it’s hard to get them to be as good as that person would be at that style. I think it’s kind of like an orthodox fighter fighting a southpaw. You just don’t see it as much.”