Issue 083

December 2011

As the UFC looks to continue to break down borders, Fighters Only visits one of the biggest populations on the planet to unearth the secrets of its own hand-to-hand combat pedigree

Hall of Fame legend and former UFC and Pride champion Mark Coleman may well be known as the ‘Godfather of Ground ‘n’ Pound’ – but it appears his adopted grounded striking style dates back a little earlier than even ‘The Hammer’s heyday.

Historical texts from Greece and Rome are punctuated with tales of gladiatorial combat and brave Olympian endeavors – but there is another ancient society with a proud pugilistic past.

The Srimad Bhagavatam, one of the most important and sacred collections of stories of India, contains numerous accounts of Hindu god Sri Krishna’s striking and grappling methods, which he uses on various warriors, both human and demonic. In Book 10, Chapter 44, Text 21, Sri Krishna is competing against his vicious uncle’s royal wrestlers. The wrestler uses a tactic on Sri Krishna, which sounds very familiar: “He with the speed of a hawk falling upon Him, both his hands clenching to fists, struck Vasudeva (Krishna), enraging upon his chest.” But Sri Krishna endures the powerful blows and escapes by grabbing the wrestler’s arms. He then pulls him around and slams him down with such force that he stays down, permanently.

Meanwhile, in another ancient Indian epic, Mahabharata, a mighty warrior named Bhima, demonstrates his grappling and boxing skills on Jarasandha, a nasty warrior king. According to the Mahabharata, Book 2: Sabha Parva, Chapter: Jarasandha-vadha Parva, Section XXIII: “And grasping each other in various ways by means of their arms, and kicking each other with such violence as to affect the innermost nerves... The heroes then performed those grandest of all feats in wrestling called Prishtabhanga, which consisted in throwing each other down with face towards the earth and maintaining the one knocked down in that position as long as possible… At times they twisted each other’s arms and other limbs as if these were vegetable fibers that were to be twisted into chords. And with clenched fists they struck each other at times, pretending to aim at particular limbs while the blows descended upon other parts of the body.” Then in the next section, we’re informed how Bhima ends the fight: “…Bhima pressed his knee against Jarasandha’s backbone and broke his body in twain.”

Both of these ancient scriptures refer to tales from around 400 BC, which would tie in with a relationship India likely had with the most widely accepted original form of regulated hand-to-hand combat: pankration. Alexander the Great actually visited India back in 326 BC. And when he finally managed to force his way into Punjab, he is reported to have shared some Greek culture with the natives, including combative arts. The Indians are believed to have then incorporated some of those fighting skills into their own fighting arts.

The most sought-after Indian combat sport was that of vajramushti, which translates to English as ‘thunderbolt fist.’ It is the fighting art of the Jyestimalla clan and derived from the use of a spiked knuckle-duster, which fighters would wear on their right fist. Contestants would both grapple and strike, and with a weapon thrown in, you can be sure it would get bloody. Aside from the weapon, the fighting style is reminiscent of Greek pankration.

Many folks in India are avid fans of kabbadi, the sumo-like wrestling match where athletes have to push one another out of a confined area, but vajramushti predates this by some millennia. Yet it has become so rare that many Indians themselves are unaware of its existence. Traditional Indian martial arts, in general, have long been overshadowed throughout Asia by the martial arts culture of China, Japan and Korea. But vajramushti dates back further than all known Far Eastern fighting styles.

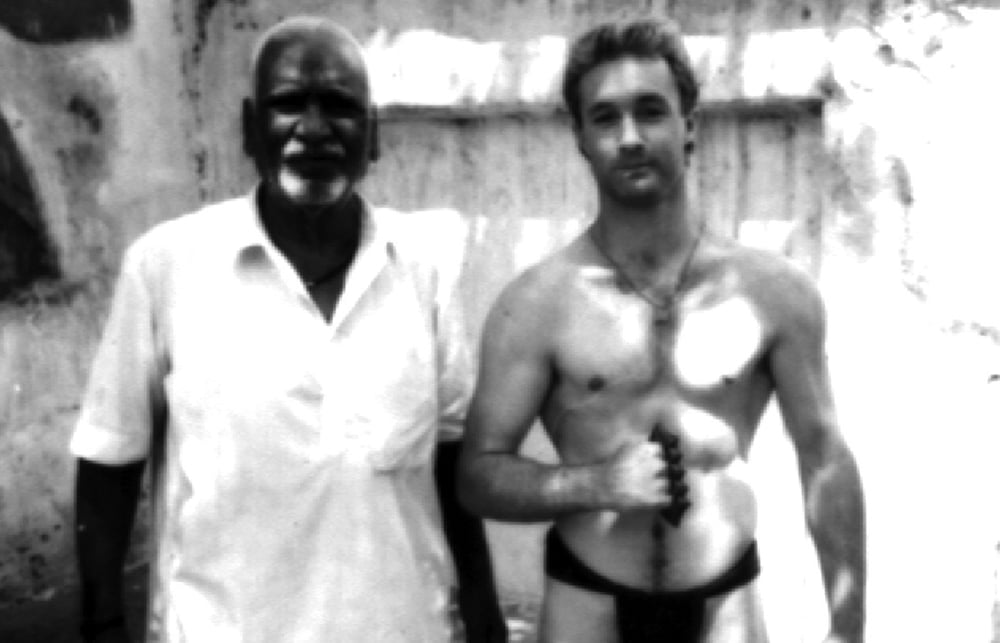

One Westerner noted for training in vajramushti with the infamous Jyestimalla wrestling clan in Gujarat, Western India, is John Will (www.bjj.com.au), a renowned Australian martial artist who has trained with grappling legends Gene LeBell, the Gracie and Machado brothers and many others. While his own array of students include a handful of UFC and BJJ champions.

Fighters Only asked the Sydney native about his experiences of this ultra-violent and almost-extinct Indian fighting art.

He says: “I actually discovered vajramushti by chance when I was traveling and training throughout India back in the late 1980s. In fact, I was doing some research at the National Library in New Delhi, when I came across a copy of the Mallapurana. Having gleaned a few hints where the Jyesti clan might be living, I began my search for them and ended up in Baroda, in the state of Gujurat.

“I met two surviving elders of the Jyesti’ clan and stayed with them for several weeks, it was a wonderful experience. These were the men who proudly bore considerable scars from their early days as vajramushti fighters. They took me to a small training space, which consisted of a dirt pit surrounded by various statues and carvings of the deities important to Indian wrestlers, inside a very old building. From them I learned some of the fundamental vajramushti techniques and training methods. It was a special time.”

John admits that it proved impossible to place a date on the actual origins of the combat art, as the texts where only translated into English around the 17th Century from the ancient devanagari (old Indian alphabet) script, or even at which time, if at all, it actually became something of a recognized sport.

“I know that vajramushti, as a sport, existed as early as the 12th century AD for example, as there are records. But not much detail is available about the specific training methods used at that time.

“But, unlike modern mixed martial arts, my understanding is that there were very few, if any, rules. The contest was fought until one fighter submitted or a referee called a stop to the fight after a fighter had been rendered unconscious.

“I don’t even think there were many safety practices used in the actual vajramushti match; it was an exceedingly brutal sport; and was ultimately outlawed in most states. At one time, a Gujurati king proclaimed that it was so dangerous that only those of the Jyestimalla clan were allowed to practice and compete.”

In daily practice though, instead of using the actual weapon (the knuckleduster), John reveals that fighters would use a cloth wrapped and bound around the right hand, that had been dipped into a red powder to help identify where the blows have landed.

Another enlightening aspect was the pre-fight ritual that the combatants would have to go through. John reveals: “On the day of the fight, the wrestlers have their heads shaved except for one tuft of hair. They have their bodies smeared with red ochre; they break a coconut at a small temple dedicated to the worship of the goddess Limbaja and they go to the arena jumping in a zig-zag fashion as the crowds follow them. Once at the arena, the vajramushti weapon is secured – tied with a red thread – to their right hand. Then the fight begins.”

As far as the ancient historical records read, women were never allowed to practice the art. While in the last few centuries, the Jyestimalla fighters were farmers, factory workers and alike. All of whom are vegetarian, and Hindu worshippers of Krishna.

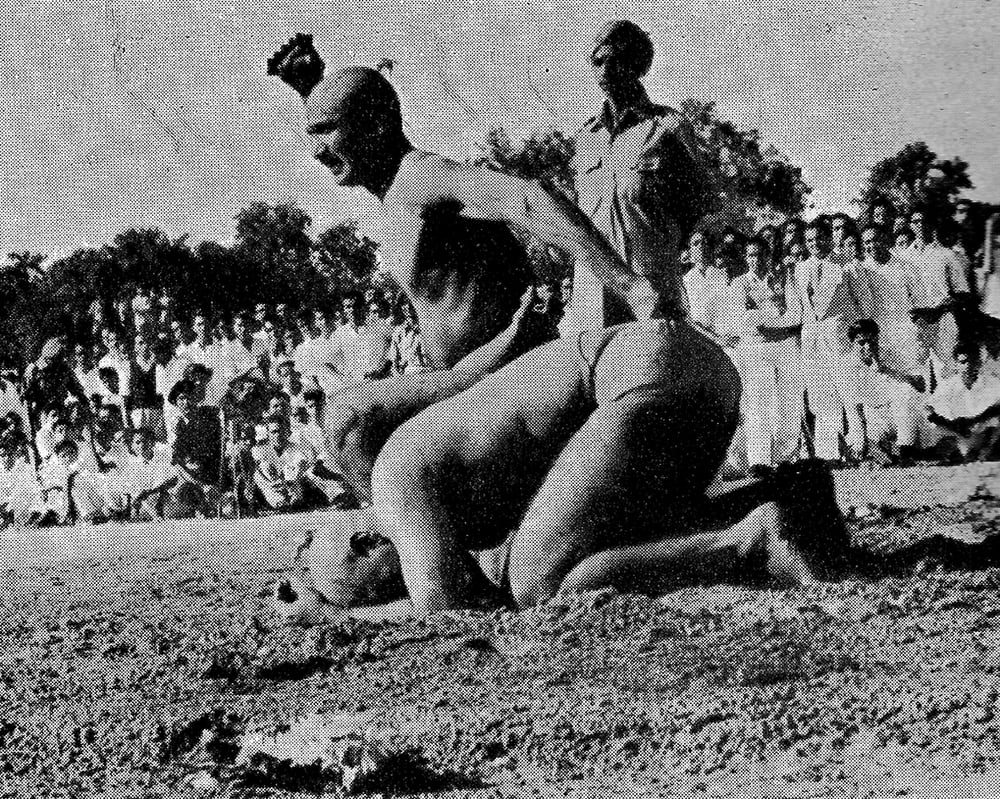

Although on the verge of it, vajramushti hasn’t yet met its extinction. Today one can still see fighters bashing one another up around September and October during the Mysore Dasara, a state festival of Karnataka, North West India. Dasara the grand culmination of a 10-day annual Hindu festival generally celebrated across India to rejoice the triumph of good over evil.

The city of Mysore has been holding extravagant Dasara celebrations for centuries and the royal family of Mysore is always at the forefront to watch the action, which includes the bloody vajramushti bouts. After a good knock-about, the fighters stand tall in their colorful loincloths and listen to the crowd cheer, all while their blood trickles down their battered limbs.

But would the style be beneficial to a modern day MMA fighter? John Will certainly thinks so. He adds: “There were some similarities, but at the time I hadn’t trained in Brazilian jiu-jitsu so I probably didn’t appreciate some of the subtleties that I was exposed to. The Jyestimallas employed techniques like the modern-day BJJ omoplata for example – but who knows what other wonderful techniques and strategies have been lost over the ages.

“I do feel very privileged to have been able to spend some time with the last surviving Jyestis of our time. And I can only hope that when MMA finally conquers the great Indian landscape – and it will – that the ancient art form of vajramushti, and India’s other traditional combat arts, are recognized as playing a part in the evolution of combat sport.”