Issue 078

August 2011

From anti-bullying to honoring servicemen, today’s MMA stars are fighting to give something back.

They say charity begins at home and, in the case of former UFC heavyweight Tom Murphy, no truer word has ever been spoken. “My parents ran a mission home, where they took people off the streets of Philadelphia and gave them a roof, bed and food,” explains the one-time Ultimate Fighter representative. “I actually came home from school one day to find my parents had given up my bedroom to a homeless man and that I would have to make do with a bathtub for a week. I used to think all my friends had homeless people living with them.”

Alone with a rubber duck and his thoughts, that day Murphy was offered an early insight into human behavior, sacrifice and the need to help those less fortunate. By the time he grew up, moved to the state of Vermont, raised four kids, dabbled in both collegiate wrestling and professional mixed martial arts and worked various other jobs, Murphy was a human being influenced and moulded by his experience in the bathtub.

As a professional fighter, that guy happened to be a heavyweight contender with a 6-0 record. He appeared on season two of The Ultimate Fighter and impressed enough on the show – losing only to eventual winner Rashad Evans – to earn himself a follow-up fight and, indeed, victory at UFC 58. A breakthrough moment in the eyes of many, Murphy sighs when reminded of the fact that first UFC knockout win arrived five years ago. He has fought only three times since and is now 36 years of age.

“In terms of my own career, I just let it roll,” says Murphy. “I’m 36 and have four kids. It’s not the ideal set-up for an aspiring fighter and I don’t really know where my career will take me from this point.”

Murphy still trains, of course, and a single appearance in 2010 resulted in a positive first-round knockout victory, but it’s fair to say the humanitarian in him has overcome the carnivore and he no longer craves knockouts and titles the way he once did. At 36, Murphy, the fighter, is now promoting the disappearance of conflict and confrontation as chief spokesman for Sweethearts and Heroes, a non-profit organisation that aims to put a stop to bullying through pro-active commitment to education.

“One day I was told about a couple of bullied school kids in New York who made some destructive decisions and took their own lives,” recalls Murphy. “Now, I have four kids at home between the ages of 13 and seven, but all my kids are home-schooled and I don’t really face these kind of problems. So I started looking into it, and I started talking to parents of children who had taken their own lives, and it really resonated with me.”

Murphy works on Sweethearts and Heroes with Jason Spector, a fellow New York native and former high-school wrestling graduate, and their efforts are endorsed by none other than UFC welterweight champion and Murphy’s training partner Georges St Pierre, himself an unlikely victim of playground bullies.

“A lot of the scars I have in my head are from being bullied at school, not from mixed martial arts,” admits St Pierre. “People find that hard to believe. They see me as UFC champion and assume that I’ve always been the one handing out the beatings. That’s not true at all, though. The most pain I ever suffered was when I was growing up in school.

“Competing in mixed martial arts is easy compared to what I had to go through as a child. You’re afforded weeks and months of preparation time for a fight in the UFC. You can train your body and mind to get ready for a fight. You know the time, place and reason for your next fight. You can visualize the outcome. On the school playground it’s completely different. I often didn’t know when a fight would break out or why an older kid would be kicking and punching me.”

Heavily influenced by his father, St Pierre found kyokushin karate and martial arts and, though it took time, confidence and physical strength would later find him.

“I remember at 14 years of age I was probably the strongest guy in school,” adds GSP. “I wasn’t the tallest, but I was the strongest. Everybody knew it. I was stronger than all the other athletes, all the older guys and was even stronger than my own dad. We would mess around on the school field and I would take down the biggest, tallest guy in the school at will. It wasn’t even a contest.

“I just wanted to feel strong so that I could have the confidence to stand up for what was right. By the time I was 14, I was no longer scared to stand up for myself. The bullies knew that, too.”

St Pierre has told Murphy stories of juvenile defiance in between practice sessions and both are now allies in the pursuit of prevention. “Everybody has a bully story,” continues Murphy. “Even if bullying hasn’t directly impacted you, I guarantee you know somebody that has experienced it and I guarantee you’ve seen it going on.”

According to Murphy, the Sweethearts and Heroes name has roots in the 16th Century, where the term bully originally meant sweetheart, but then centuries later became perverted when pimps would bully men into handing over their so-called sweethearts. As for the heroes part, Murphy only wishes more of us were familiar with the universal meaning of the word.

“It’s estimated that 85% of all bullying takes place in front of bystanders,” says Murphy. “Whether you’re a bully, victim or just some guy passing by, we all see it and we all know what’s taking place. We all have the power to become somebody’s hero, yet very few of us are willing to take that role. I’ve heard bullying stories from middle-aged men and they all remember who their hero was, even 20 years down the line. If you can get kids to realize they are bystanders and that they can do something with the power that comes with it, then you can start really making a difference.”

In terms of spreading the word, Murphy and company, all blessed with similarly sized muscles and cauliflower ears, attach themselves to schools across America and speak of the ills of bullying, as well as suggest coping methods. Describing his looks as that of a ‘mean and moody action figure,’ Murphy believes this stark contrast in image and message is what ultimately works.

“It’s great when we do presentations, because we talk a school into letting us speak to their kids and then the first thing we do is show them a load of fight scenes and loud music,” laughs Murphy. “I then walk out and start discussing bullying and everybody is like, ‘What is this guy talking about? We were just watching fights a few seconds ago.’ I take the chance to educate them on mixed martial arts and tell them it’s not a fight, it’s a competition, and that the sport transfers possible negative energy into positive achievement. We then get right into it and give them the steps to avoid bullying from each and every angle.”

Of course, the fighter or wrestler-as-bully stereotype is something that continues to stain combat sports and is a weapon the uneducated will continually turn to in the heat of debate. However, Murphy’s unique position as fighter and anti-bullying campaigner has allowed him a clearer understanding of his sport, its implications and his own inner psyche.

“I don’t think I was ever a bully in the truest sense, but I had the propensity to be a bully, and that was because I was so hyperactive and wild through adolescence,” admits Murphy. “I didn’t have a channel for all that excess energy and aggression until I found wrestling at college.

“I’m very conscious of the fact that I could have and probably did bully certain people on my way to adulthood. It was never done maliciously or with any evil intent, but I’m aware that I had those traits. I’m certain that if I went back and spoke to my peers at elementary and middle school they’d say, ‘No, Tom, you were a bully.’ That means a lot to me when I reflect back on my life and how my early experiences have moulded where I am today. A lot of these wrestler types may not think of themselves as bullies at college, but a lot of their peers will do.”

COUTURE’S G.I. FOUNDATION

The fighter-as-carer stereotype is one never tipped to catch on, but it’s true – mixed martial artists are just as likely to extend a helping hand as a jabbing hand. The all-giving Randy ‘The Natural’ Couture and his non-profit Xtreme Couture G.I. Foundation raise money and awareness for those wounded in combat, while Rich Franklin’s Keep It In The Ring Foundation advocates non-violence and the building of character in youngsters, a message spread through after-school sports, martial arts and life-skill programs.

Sometimes fighters even take their charity into the Octagon, as is the case with Phil Davis and his striking pink shorts, a nod to the American Cancer Society and its ongoing search for a cure. While UFC president Dana White regularly gives away huge sums of money to charitable and lost causes that pluck at his heart-strings.

And most recently, New Zealand light heavyweight James Te Huna warmed the hearts of even the most cynical in February when, after taking his first career UFC loss, the 29-year-old donated his entire fight purse to the Red Cross Christchurch earthquake relief effort.

“It was three or four days before my last fight and I was sat watching television in my room when I heard news of the earthquake,” recalls Te Huna. “I was born just outside Christchurch, and a lot of my cousins, as well as my grandparents, still live in the area. I didn’t have to think too long or hard about donating my fight purse to the Red Cross.”

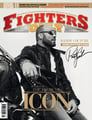

COUTURE ICON ISSUE: CHRIS LYTLE

“He took things to the next level. Before him, people were very good at one aspect and just tried to get by with the others. He helped change that. And his ability to defeat great fighters after I thought his best days were behind him still baffles me. I don’t care if he came back in five years, I would never count him out”

...