Issue 073

March 2011

With the UFC’s return to Brazil after a 13-year hiatus all eyes are on the South American nation. You might know the history but what about the here and now? FO finds fighting spirit among the favelas

Mix of the MMA world’s highest-profile title belts belong to Brazilians. Notice, if ever it were needed, the 3.2 million square mile country has an uncanny ability to produce world-dominating talent. And all in the face of widespread social turmoil.

Brazil is, of course, the home of vale tudo, no holds barred fighting, MMA’s forebear. From the Gracies’ open challenge to traditional martial arts, to jiu-jitsu’s intense and malicious rivalry with luta livre, formative moments in the history of mixed martial arts will be entwined with Brazil forever. And so too will be the UFC’s 2011 return to the cradle of the sport. August’s UFC: Rio event promises to not only be a massive success for the Las Vegas company but for Brazil too and the mixed martial arts scene it nurses.

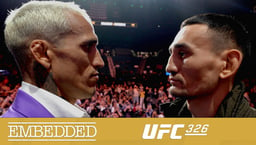

And quite the crop of devastating young fighters the South American country has produced in recent times: ‘Fighter of the Year’ and UFC 145lb champion José Aldo, Junior dos Santos, Charles Oliveira, Strikeforce middleweight title holder ‘Jacare’ Souza, former Dream featherweight king Bibiano Fernandes, Strikeforce light heavyweight champ ‘Feijão’ Cavalcante, Sengoku boss at 185lb Jorge Santiago, and the promotion’s former 145lb number one Marlon Sandro – not forgetting established elders like UFC middleweight and light heavyweight supremos Anderson Silva and Mauricio ‘Shogun’ Rua. But for a nation so bewitched with MMA, and one possessing such a complex relationship with the sport, it’s startling to discover that today’s influx of modern Brazilian wrecking machines not only struggle against the divide between Brazil’s rich and poor, but they trace their roots to the unlikeliest of places: the death of Japanese super-promotion Pride.

Although historically only the middle classes of Brazil practiced MMA, even the slums of the country have now embraced it. Termed ‘favelas’, these run-down, low-income ghettos account for the housing of 50 million Brazilians (only threatened in number by China and India). At least 50% of scraps on modern Brazilian events will consist of favela fighters. While years ago many of these upstarts may have looked to emulate rags-to-riches soccer players such as Romario and Ronaldo, they now idolize Anderson Silva and José Aldo. “I see the MMA today following the path of soccer,” explains former UFC and Pride heavyweight champion Antonio Rodrigo Nogueira. “It’s popular in all sections of the population who see the sport as a real chance to improve the social level, and, besides earning money, can represent the country abroad.”

UFC middleweight, and Brazilian jiu-jitsu black belt, Rousimar ‘Toquinho’ Palhares is one of the early batch of slum fighters to live that dream. Born in Dores do Indaiá, a municipality 630km northwest of Rio de Janeiro, for a time Palhares ate pig feed with his 12 brothers in order to avoid starvation, such was the hardship he experienced in his younger years. Initially a move to Rio to follow his dream of becoming a mixed martial arts champion saw him fare no better – being forced to sleep under shelter of a bridge on multiple occasions. Finally the stocky 185lb’er, now 11-3 in pro competition, scored a spot on Brazilian Top Team’s pro squad and in turn a small team-owned apartment, behind the gym, with two more fighters. “Here is perfect for me because I don’t miss any training,” says Rousimar of the home in Rio’s Cruzada São Jorge community.

Poverty isn’t the only challenge in the country’s favelas. The lure of ‘easy’ money in the drugs trade frequently proves too powerful for promising, although financially troubled, young fighters. Roughly 20% of Brazil’s prison population is locked up for drugs offenses. Even Ronaldo ‘Jacare’ Souza, Strikeforce middleweight champion, committed petty crime during his poor childhood in the state of Espirito Santo; proof that no matter your nascent potential the temptation is still present. It was a course that was only righted when his mother sent the future BJJ black belt to the commercially inclined city of Manaus in northern Brazil, where he discovered jiu-jitsu.

Astonishingly, some talent has emerged from even the immensely violent Vila Cruzeiro favela, home to one of the largest drug-trafficking headquarters in Rio de Janeiro. “I was born and raised with many guys who went to the wrong life,” explains André ‘Chatuba’ Santos, a Vila Cruzeiro native who is considered one of Brazil’s most promising welterweights. “But I chose the path of being an athlete while they chose another way; and I respect them.” In fact, the area’s neighboring Complexo do Alemão slum is so ridden with crime the Brazilian army, navy and special ops forces (BOPE – of which UFC welterweight Paulo Thiago is a member) recently assaulted the area with tanks and armored vehicles in order to combat drugs barons. Santos, a 22-4 luta livre exponent, states: “Many times I had to abort going to training because of confrontations between the police and the criminals close to my house. I feel like I’m in a war zone. Young guys who live here must have the willpower to not succumb to drug dealers’ offers and follow the wrong path. I saw many friends who trained with me surrender. Today many of them are dead or in jail.”

Former Pancrase and Sengoku featherweight champion Marlon Sandro knows intimately what it’s like to lose friends in the mire of Brazil’s underworld. At 17 years old, while working as an office boy, Marlon was introduced to Nova União head coach André Pederneiras via a friend, Hudson. While Marlon was shown a new future via fighting, Hudson ended up deep in the drug trade to which he eventually lost his life. Aside from fighting, Marlon runs free MMA lessons, with the support of Pederneiras, for children of his community. “It took many children away from the crime life, but I lost a boy who I thought would be a phenomenon,” says Marlon. “The kid ended up being murdered.”

Despite the hardship in much of Brazil, there is promise in the sport of mixed martial arts. Nova União, with its league of favela stars, can make a serious case for being one of Brazil’s strongest young fight teams. Specializing in, though not bound to, welterweight and below, it has produced aforementioned featherweight champs José Aldo and Marlon Sandro, as well as former UFC 185lb number one contender Thales Leites, and a wealth of up-and-coming talent like Dream’s Léo Santos and the UFC’s Renan Barão. “Every training session here is very tough. It makes the fight easier than the sparring itself,” explains Aldo from the gym’s base in Rio’s Flamengo district. Co-founder André Pederneiras is often credited with the success of the team. “Many people point toward Greg Jackson as the best coach in the world, but Greg gets most fighters ready by just using a nice strategy,” argues Thales Leites. “Pederneiras got most of those guys in slums, like José Aldo and Marlon, allowed them to sleep in the academy, gave them sponsorship, taught them jiu-jitsu, taught them to be good strikers and then MMA world champions. That’s far and away more difficult.”

Nova União isn’t alone in producing thrilling young Brazilian fighters. In keeping with its modern boom, there’s been a constant stream of them emerging on what seems like a monthly basis for two or three years. Why? Ironically, the subsidence of two of the country’s most prized jewels: Chute Boxe and Brazilian Top Team.

Between its 1997 inception and its 2007 demise, Japanese promotion Pride offered thrilling scraps aided no end by the world-class products from Brazil’s two grandest fight factions: the jiu-jitsu players of Brazilian Top Team and the Muay Thai practitioners of Chute Boxe. While the two camps’ exclusive relationship with the Japanese promotion established Brazil’s biggest fighting stars, it forced a monopolization of an entire nation of talent. For a full decade, Brazilian fighters who desired to slide on a pair of gloves in the sport’s largest attraction would need to be a product of either Curitiba’s Chute Boxe or Rio’s Brazilian Top Team. No other gyms were afforded entry due to those teams having sole Brazilian access to the organization. In turn, great Brazilian teams such as Nova União, for example, were either unable to source the country’s most promising fighters or unable to find lucrative fights for their scrappers; the UFC fluctuating between boom and bust in Pride’s lifetime.

While Pride’s dissolution in 2007 was marked as a scathing body shot to the sport, it cued an ultimately beneficial weakening of Brazil’s dominant fight factions. With Chute Boxe and Brazilian Top Team no longer possessing the only direct line to a fighter’s biggest payday in Pride, stars such as Wanderlei Silva, Shogun Rua and the Nogueira Brothers were free to form their own fight teams – Wand Fight Team, Universidade da Luta and Nogueira Team respectively. A choice no doubt assisted by not having to pass on the typical 20–30% of their purses to their handlers. Top trainers defected too, like Rafael Cordeiro (Chute Boxe linchpin), who went to the USA and opened his own Kings MMA, and Cristiano Marcello (Chute Boxe jiu-jitsu instructor), who founded Curitiba’s CM System.

The biggest names then stepping into the UFC’s Octagon forced a significant, positive shift in Brazilian MMA. Now top prospects like Demian Maia, Paulo Thiago, Lyoto Machida and many others that didn’t belong to BTT or Chute Boxe could finally have an opportunity. Today, almost all of Rio’s MMA academies have fighters in large international organizations thanks to the democratization of opportunities left by the ebb of the Brazilian scene’s twin pillars. Nova União has José Aldo, Renan Barão, Williamy ‘Chiquerim’, Amilcar Alves, all of the UFC, as well as Marlon Sandro, the former Sengoku and Pancrase featherweight champion. Furthermore, Gracie Fusion produced Rafael dos Anjos (UFC), while X-Striker boasts Ronaldo ‘Jacaré’ Souza (Strikeforce) and promising free agent André Galvão. Aside from established stars like ‘Big’- and ‘Little Nog’ and Anderson Silva, Nogueira Team has Junior Dos Santos and Fabio Maldonado (UFC). And although it can’t offer the same depth of talent as its mid-2000s heyday, Brazilian Top Team still has the dangerous Rousimar Palhares (UFC).

Obviously, homegrown promotions are playing a massive part in Brazil’s MMA growth too. Even with low sponsorship support and ticket sales, a persistent event calendar – due to organizers like André Pederneiras (Shooto Brazil), Wallid Ismail (Jungle Fight), Amaury Bitetti (Bitetti Combat) and many others – is feeding both fighter and fan hunger for the sport. “We have so many tough guys in Brazil that any event is seen as a possible way for them to show their value and reach their dreams,” explains André Pederneiras, gym-master of Nova União. “That’s why it was so important for me to organize Shooto in Brazil. Before Shooto, Nova União was recognized in Brazil, but my lightweight guys had no opportunity. Putting [events on for] my fighters to fight opened many doors and changed that situation.” But while the opportunities might be there the money often isn’t, both for promotions and fighters. A passion for the sport is a necessity. Most fighters starting out earn less than $300 US a go. In certain small events in the north and northeast of Brazil some even scrap for free. Even in that climate, Jungle Fight, currently the most successful Brazilian MMA event, still launched names like Lyoto Machida, ‘Jacaré’ Souza and Fabricio Werdum. However, Wallid Ismail, essentially Jungle Fight’s Dana White, is one of the few promoters who can get sponsorship from local state governors. He states: “People have no idea how hard is to make an event in Brazil. But I do it because I really love this sport.”

Although mainstream acceptance may not have followed suit, Brazil has always possessed an immense zeal for the sport of mixed martial arts. In fact it’s a testament to fans and fighters that it has been, and continues to be, so fruitful for world-beating brawlers, grapplers and tacticians. “Today, MMA is growing a lot in Brazil,” confirms Rodrigo Nogueira. “In the United States it’s already one of most popular sports. The more Brazilians win there, the more opportunities they will give to the new talents here. The deal is to focus. Those who can train and achieve good results will have their place in the sun.” With the blast of awareness the UFC’s mega-bucks move into Brazilian territory will bring, the country’s MMA future is blindingly bright.

Media studies

Despite Brazil’s vale tudo and jiu-jitsu roots, as well as its Pride success, MMA has been considered a police case by Brazilian press for years. However, with a recent surge of interest in the country in line with the rest of the globe, mixed martial arts has finally started to gain some recognition as a legitimate endeavor from media entities. Television programs now court Anderson Silva and ‘Minotauro’ Nogueira with invitations, and gradually the printed press has cracked open column inches for UFC champions. While the biggest TV network, Rede Globo, is still reluctant to embrace MMA, Brazil’s third-largest station, Rede TV, produces a Saturday-night show dedicated to the UFC. Predictably excellent audience numbers have excited Rede TV directors and other clued-up channels with all now keen to clear more space for added coverage. As ever, the country boasts multiple MMA-specific media sources too. Tatame and Gracie magazines are both printed and have counterpart websites, while portaldovt.com.br (or Portal do Vale Tudo) is essentially the Sherdog of the Brazilian scene. Furthermore, MMA-dedicated cable channel Combate would make most Western MMA fans salivate; its 24/7 fight coverage includes broadcasts of every UFC event live to almost 100,000 subscribers nationwide.

Rio bravo

A lengthy 13 years after São Paulo hosted Ultimate Brazil, Rio de Janeiro will stage only the second UFC event in the country on August 27th at the 18,000-seat HSBC Arena. “It was in Rio that my family started vale tudo almost 80 years ago,” says Royce Gracie, at the press conference for UFC: Rio before more than 300 members of the media. “It’s good to see the sport returning to its origin.” The announcement – which took place at Palácio da Cidade, the official residence of Rio’s mayor – boasted the attendance of Anderson Silva, Shogun Rua, José Aldo and Vitor Belfort, any of whom could be appearing on the card. “Believe me when I tell you,” offers Dana White, UFC president, “we’re going to bring you a good card and you will have your Brazilian favorites on the card. I guarantee you.” He later added: “When you get inside that arena, what I call ‘the UFC virus’ will spread. This isn’t a test. This is going to work in Brazil.”

Best Brazilian young guns

Renan Barao, bantamweight, 25-1 (1 NC)

A Nova Uniao product considered just as lethal as his stable mate José Aldo, bantamweight Renan ‘Barão’s 21-straight wins may mean he’s a future contender for Dominick Cruz’s UFC title. His only loss was in his first pro fight, and before transferring to the UFC roster wrenched out two WEC submission stoppages.

Johnny Eduardo, featherweight, 24-8

The current 145lb champion of Shooto Brazil, Nova Uniao’s Johnny Eduardo might have began his fighting life a Muay Thai black belt, but he has become a complete mixed martial artist under André Pederneiras. Fighting since 1996, Eduardo has gone 10-0 after hooking up with the super-coach three years ago.

Bruno Carvalho, lightweight, 12-4

Considered the best striker of all Brazilian lightweights in Muay Thai rules, Bruno has dedicated himself to MMA training in the past two years under former Chute Boxe BJJ coach Cristiano Marcelo at CM System. His 6’ 1” stature will make him a tough fight for anyone at 155lbs.

Antonio ‘Toninho Fúria’ Glaristone, lightweight, 10-6

‘Toninho Fúria’, a name he’s typically known by, is a natural lightweight who’s already beaten two of Brazil’s most talked about welterweights at their 170lbs limit: Diego Braga and Igor ‘Chatubinha’. Now moving down to 155lb, Brazilian fight fans are excited about his potential.

Erick Silva, welterweight, 12-1 (1 NC)

With Erick ‘Indio’ Silva being pegged by his training partners as the next Anderson Silva, there’s a sizeable buzz around the Nogueira Team fighter. Holding the Jungle Fight welterweight title, Silva is rumored to be close to signing with an international fight promotion.

Vitor Vianna, middleweight, 10-1-1

A BJJ black belt and an instructor with Wand Fight Team in Las Vegas, Vitor Vianna has the chops to establish himself as a dangerous 185lb’er. Before he spent a year in Holland honing his Muay Thai, Vianna’s only loss came due to injury from the UFC’s Thiago Silva at 205lb.

Marcos Rogério ‘Pezão’ De Lima, light heavyweight, 8-0

Since Marcos’s Muay Thai circuit days saw him go 79–6 it’s no surprise he’s notched eight wins and no defeats within barely two years of MMA competition. A fantastic sprawl and brawler, ‘Pezão’ caught the eye of American events with a decision win over former WEC middleweight champion Paulo Filho in late 2010.