Issue 032

December 2007

While the modern era of North American MMA began with the first UFC pay-per-view in November 1993, and the historical roots can be traced back to the Gracie family’s mid-twentieth-century exploits in Brazil, the sport’s Japanese development was very different.

Every historically important figure and vital event in the sport’s origin and development in Japan is in some way linked to the world of Puroresu, or pro wrestling. This article will explore how the essentially quite silly form of physical theatre (men in their underpants pushing and shoving each other) evolved into, at one point, the most mainstream national scene in MMA history. With a national culture steeped in the martial arts, and the home to judo, jiu-jitsu, karate, and aikido, Japan would likely have embraced MMA even if Puroresu had never existed, but would almost certainly not been such a widespread, lucrative success as it became.

In the beginning there was… Rikidozan

Introduced to Japan after the Second World War, Puroresu thrived in the 1950s as the nation found a new hero in former Sumo wrestler Rikidozan. A powerful man, his ‘battles’ with gigantic foreigners drew some of the biggest ratings in the history of Japanese TV. Rikidozan himself had only a passing connection to the evolution of MMA but his status within Japanese culture is important to this story.

Without Rikidozan, Puroresu would never have gone mainstream, and would never have gripped the nation so tightly or for so long. Ever since him, Japan, an essentially insular and somewhat xenophobic nation, has been in search of a comparable hero. In the early to mid-1950s one of Rikidozan’s main rivals was Masahiko Kimura, a judo legend famous in MMA circles for defeating the near-mythical Helio Gracie in 1955.

Rikidozan did what Helio couldn’t. He battered Kimura, destroying him with palm strikes, kicks (some of them to the groin), knees and head butts. Of course, this was because Rikidozan double-crossed Kimura during a cooperative performance in what was in reality a cowardly assault, but to the fans, he was simply the strongest Japanese fighter.

Antonio Inoki and Karl Gotch: In search of legitimacy

In 1971, almost a decade after Rikidozan’s death (he was stabbed in a nightclub by a Yakuza thug in 1963) Karl Gotch arrived in Japan and started Puroresu’s mutation into MMA. A somewhat successful pro wrestler in the US, Gotch became ‘the God of Professional Wrestling’ in Japan. Gotch trained and mentored all the most important figures in this narrative, starting with Kanji ‘Antonio’ Inoki.

Gotch’s style – a blend of amateur and catch-wrestling styles with fast movement on the mat and plenty of suplexes and submissions – was a hit in Japan where the pro wrestling audience cared less for flashy gimmicks and more for technical skill. Molded by Gotch, Inoki viewed Puroresu as a pseudo-martial art, and in 1976 began an infrequent series of ‘mixed matches’ against fighters from other disciplines.

Inoki’s ‘fights’ saw him defend his art against top-ranked judokas, heavyweight boxers and karate champions. Inoki almost always won these ‘worked’ matches, but his most famous match was a very legitimate fight.

In June 1976, he faced Muhammad Ali in a match where Inoki was scheduled to take a beating but miraculously come back to win. Ali’s advisors tried to persuade him to back out. Unfortunately, there was too much money at stake and consequently, no going back. Instead, the two men went into the ring with no plan and no predetermined ending. They would fight for real.

With rules outlawing most of Inoki’s throws and submission holds (training under Gotch gave him real submission skills) all he could realistically do was lie down and throw kicks at Ali’s legs, which he did for fifteen rounds.

An utter fiasco, the fight was ruled a draw, despite Inoki landing his kicks and Ali not landing a single punch. The fight’s sheer awfulness seriously damaged the Puroresu scene for a few years, but it would attain legendary status in the late 1990s as revisionist history tagged it as the first genuinely high-profile ‘mixed martial arts’ contest.

Satoru Sayama and Shooto

Few people help to genuinely revolutionize their chosen field. Even fewer help do it twice in completely different ways. Sayama, the original Tiger Mask (and the man Gotch viewed as his best student) is one of those very few. His high-flying style changed Puroresu forever, but his quest for more realism also helped pave the way for the rise of Japanese MMA.

Having achieved superstardom on the back of spectacularly athletic but thoroughly unrealistic action, Sayama abruptly retired at the height of his fame in 1983. Heavily influenced by Gotch, he resurfaced a year later, as a major star for the UWF (Universal Wrestling Federation). Still a form of Puroresu, it was more realistic looking than the established promotions and was the first sustained attempt to give Japanese fans a more legitimate-looking product.

During his brief retirement Sayama had established a new sport he named ‘Shooting’. He took the name from the pro wrestling word ‘shoot’, meaning to fight for real. Several years ahead of its time and run on a tiny budget, Sayama’s project flew well under the radar of mainstream popularity, but promoted legitimate fights which were recognisably ‘MMA’ back in the mid-1980s. After some management and rule changes, it evolved into the promotion Shooto, which has since expanded to a worldwide international organization. But other pro wrestlers, all of them disciples of Gotch, would take things even further.

Akira Maeda and his ‘little brother’ Nobuhiko Takada

The original UWF ran from 1984 to 1986 and can trace its roots back, not to sport or performance, but white-collar crime. In 1983 New Japan Pro Wrestling was having an incredible run of box office success. But much of the money was finding its way outside the company, funding Antonio Inoki’s various business interests and political ambitions. The details of the embezzlement remain murky but Inoki’s business manager, Hiasashi Shinma, was forced out of New Japan and set up his own company, the UWF.

Shinma took with him wrestlers Akira Maeda and Nobuhiko Takada along with several mid-level New Japan performers. Gotch student Maeda was widely viewed as the heir apparent to the 40-year-old Inoki. Gotch joined the UWF as the new promotion’s main trainer. The original UWF was a hit in Tokyo, but without TV, it was dying outside the capital. Differences over the company’s creative direction (Shinma wanted traditional Puroresu, Sayama wanted more kicks and Maeda pushed for more working of submissions on the mat) caused deep internal problems, and the company collapsed in 1986.

Most of the UWF roster headed back to New Japan where they got valuable TV exposure, and Takada in particular blossomed as a performer. Maeda became increasingly difficult to work with was eventually fired. Assembling some financial backing, Maeda reformed the UWF in 1988. The new UWF was even more realistic looking than its predecessor, but was just as ‘fake’. The wrestlers trained like real fighters but performed their matches. Much like the original incarnation, the second UWF was on fire in Tokyo but less successful elsewhere. Maeda was the big star, with the charismatic, flashier Takada close behind him. By late 1990, the promotion had collapsed, despite selling some 50,000 tickets to a Tokyo Dome event a year earlier.

RINGS, PRIDE and the new era

With the demise of the UWF, Takada and Maeda went their separate ways. Maeda formed RINGS and presented it as a new, legitimate sport. Takada formed the UWF-I (Union of Wrestling Force International) and carried on in the same vein as the UWF (fixed matches).

The rise of legitimate MMA killed off the UWF-I and it’s preferred style. Once fans saw real fights, the UWF-I looked just as fake as regular Puroresu. It didn’t help that in 1994 UWF-I wrestler Yoji Anjoh took a posse of Japanese reporters to California to issue a challenge to Rickson Gracie in his own dojo. He didn’t expect Gracie to respond, and even if he did, the larger Anjoh assumed could handle him.

Gracie annihilated him. The story was well known in Japan and the UWF-I’s fans expected Takada to take revenge. But their hero, well aware he was anything but a real fighter, stayed silent. Finally Takada agreed to face Gracie for a monstrous payoff in October 1997, and lasted less than five minutes before submitting to an armbar.

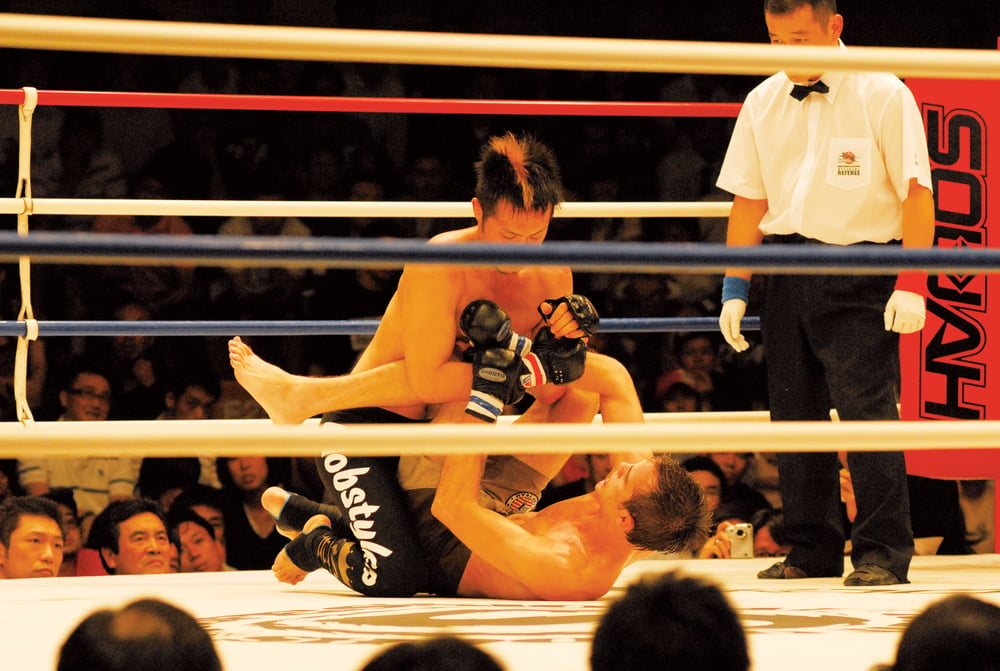

That fight was the main event of the first Pride FC show. Without Takada, the promotion would never have existed. And without Kazushi Sakuraba, a product of the UWF-I dojo, it would never have prospered the way it eventually did. It is unlikely any other Japanese fighter could have gone 4-0 against the Gracie clan, but it was Sakuraba’s run of success against the Brazilians that made Pride FC such a mainstream success and made the loveable Sakuraba a genuine national hero.

Maeda’s RINGS went from fixed fights to legitimate competition. Maeda himself never had a proper fight but after his retirement in 1999, RINGS switched to a 100% real format. RINGS struggled on into 2002, but with Pride FC swiping much of its top talent (including fighters such as Gilbert Yvel, Dan Henderson, Minotauro Nogueira and Fedor Emelianenko) the fans abandoned RINGS. RINGS’ talent scouts in Europe and Brazil helped introduce the MMA world to some of the best fighters of today. Even K-1 founder Kazuyoshi Iishi owes a debt of gratitude to Maeda and RINGS. Working for Maeda is where he cut his promotional teeth. Today, the 48-year-old Maeda is the figurehead of K-1’s MMA offshoot, HERO’s, bringing things neatly full-circle.

Suzuki and Funaki: Reality sets in

Shooto can traced back to the mid-1980s but the Pancrase promotion, headed up by young UWF mid-carders Masakatsu Funaki, Minoru Suzuki and Ken Shamrock was the first fighting promotion derived from Puroresu to genuinely capture the public’s imagination.

Maeda’s RINGS and Takada’s UWF-I were already well-established, but their matches were still generally co-operative performances. Pancrase, named by the revered Gotch after the ancient Greek Olympic event Pankration, held its first show on 21st September 1993. Aside from the discovery of spectacular Dutch kickboxer named Bas Rutten, the event was notable for its brevity and its sheer novelty. All five matches lasted less than 15 minutes combined, the average amount of time for a RINGS or UWF-I main event.

Pancrase was completely different, new and, almost entirely real. True, there were a few suspicious results in subsequent months and years but Gotch’s protégés (Shamrock was trained by Gotch’s son-in-law, while Funaki and Suzuki were tutored by the man himself) essentially realized his dream – pro wrestling as a legitimate sport.

Even the Gracie family owe an indirect debt to Gotch. Their fame in Japan was originally based on Royce beating the already famous Shamrock at the first UFC show. By the late 1990s, Pancrase was squeezed out of the big time by Pride and, to a lesser extent, RINGS. Forced to accept the more ‘brutal’ MMA rules that were now the standard and abandon its more genteel approach of disallowing all punches to the face and instead concentrating on submissions, Pancrase also had to contend with its biggest stars inability to compete at the top level. But, like Shooto, it remains a fixture on the Japanese MMA scene, and one that, like everything else over there, would never have existed without the dysfunctional relationship between Puroresu and its bastard offspring, MMA.

...