Issue 102

June 2013

The reluctance of MMA judges to score fights as draws is not only robbing fans of blockbuster rematches, but also fighters of their hard-fought acclaim and, worse still, Octagon careers.

A funny thing happened in early 2011. It seemed that no matter how hard they tried – and boy did they try – the main event stars of UFC pay-per-views couldn’t catch a win. A five-rounder between Gray Maynard and Frankie Edgar ended as a draw at UFC 125 in January, and so too did the three-rounder between BJ Penn and Jon Fitch, which took place the following month at UFC 127. Both times the decisions were roundly booed and fans and fighters alike walked towards the exits with frustration etched upon their faces.

A drawn bout leaves all involved none the wiser, yet the purpose of competing in the first place is to try and determine winners and losers. Therefore, in the eyes of fans, if no winner is determined at the end of it all, what was the point? It’s one thing witnessing a draw in a preliminary fight with no bearing on the immediate future of a division, but to see an important main event go the way of the draw is perceived as being nothing short of catastrophic.

And it appears that MMA judges at least have taken note of the fans’ reactions and got the point. Because since those aforementioned drawn main events – over two years ago now – we’ve witnessed only two further draws from more than 60 entire UFC fight cards.

These were the March 2012 flyweight tournament encounter between Demetrious Johnson and Ian McCall, which was only altered to a draw backstage in Sydney, Australia, after the fight, and then, most recently, a preliminary bout between Felipe Arantes and Milton Vieira that happened last June at UFC 147.

So, we’re honestly being led to believe that only these two fights, out of the well over 700 that have taken place in the last two years, warranted being declared a draw. Isn’t that staggering? After all, the UFC prides itself on attracting the best fighters in the world and then pairing them up.

And more often than not we witness these premier mixed martial artists go up against one another on a regular basis in what are typically competitive matches. Matches that are, for the most part, contested over just three five-minute rounds – hardly ample time for one fighter to pull away from another. So, if that’s the case, and we’ve established most fights are competitive and short, why don’t more of them end in draws? Why are fights like Maynard vs Edgar and Penn vs Fitch the ugly exception and not the rule?

Drawn on history

In truth, drawn bouts have been a rarity in the UFC since the organization’s inception. The first two occurred in 1995 and involved Ken Shamrock in tussles with Royce Gracie (UFC 5) and Oleg Taktarov (UFC 7). A stalemate was reached after lengthy first rounds had expired and no clear winner emerged.

The first draw decided by three judges took place in September 1999, when Tim Lajcik drew with Ron Waterman over three rounds in a heavyweight bout at UFC 22. After that, Brad Gumm and CJ Fernandes fought to a draw at UFC 27, and then, at UFC 41 in February 2003, BJ Penn and Caol Uno ended up tied in what was the first drawn five-rounder in UFC history. Also that year, Vernon White forced a draw with Ian Freeman at UFC 43.

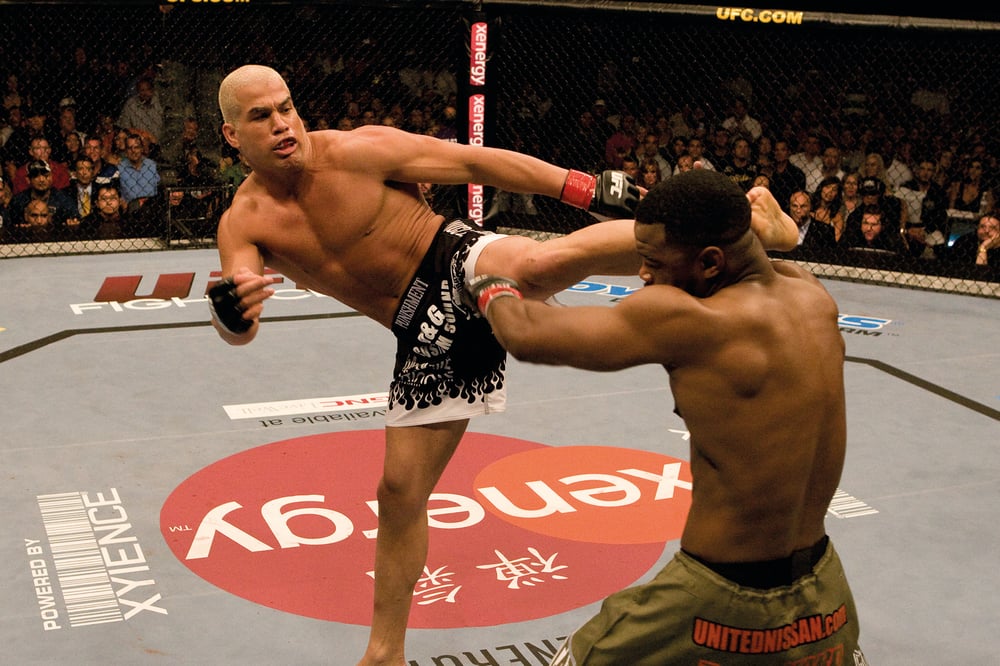

One of the more high-profile stalemates arrived in July 2007, when Rashad Evans and Tito Ortiz scrapped to a three-round draw at UFC 73. In a bitterly contested fight, a point deduction cost ‘The Huntington Beach Bad Boy’ victory. Yet the actual result, a draw, also paved the way for a rivalry between the two, one that would result in a rematch four years later at UFC 133.

Consequently, a draw simply connected two marketable stars and ensured they’d have to sort out their issue once and for all at a later date. The lucrative rematch is, therefore, another under-appreciated value of the draw. After all, if the first fight is as controversial as the draw suggests, it’s surely only right that the two frustrated fighters reconvene at a later date to settle the dispute.

In addition to the rematch between Evans and Ortiz, a drawn bout also set up highly anticipated returns between Maynard and Edgar and Johnson and McCall. And, interestingly, those rematches ended up being far more conclusive than their predecessors.

Sometimes, of course, drawn bouts don’t warrant rematches. Penn’s draw with Fitch, for example, was never the greatest fight, and both walked away grateful to have left with their dignity and having avoided a loss on their records. Meanwhile, the heavyweight bout between Travis Browne and Cheick Kongo in October 2010 at UFC 120 was similarly messy, and, again, nobody was calling for them to settle their drawn bout in a rematch.

Kongo, like Ortiz, blamed point deductions for the final result. That was also the excuse used by Thiago Tavares when he kicked a little too low, suffered a deduction and was held to a draw by Nik Lentz in January 2010. And what about Fabricio Camoes in his fight with Caol Uno at UFC 106? The Brazilian lightweight appeared on his way to winning a decision when suddenly docked a point in the second round for illegally up-kicking his downed opponent. Instantly, the tables turned and both scrapped for a draw.

Draws are synonymous with controversy, of course. Many felt Arantes deserved to beat Vieira last year, and many more felt Jesse Bongfeldt was worthy of a victory in his draw with Rafael Natal at UFC 124. It’s the nature of the beast, the nature of the draw. But, still, nobody lost. Far better to feel hard done by following a draw, than a defeat. Draws can lead to rematches, whilst defeats can lead to the chop. There’s really a very fine line between the two, yet it can make or break a career.

In a soccer match, if a referee is unsure of a decision – be it a penalty or a goal – they are advised to err on the side of caution and to only give it if they see it. If missed, they hand the benefit of the doubt to the defending team, as a 0-0 scoreline is far more manageable than a controversial 1-0 result. So, shouldn’t the same rule apply to the fighting arts too?

Let’s look at a few controversial fights that have taken place in the past couple of years and see if any of those could have benefited from being called a draw and thus teed up for a re-run. Nick Ring’s win over Riki Fukuda? Check. Chael Sonnen over Michael Bisping? Double check. How about Takeya Mizugaki’s loss to Chris Cariaso, which was so bad the UFC ended up paying the Japanese star a win bonus anyway?

These controversies could have all been simmered if the judges showed a greater propensity to hand out 10-10 rounds, and not look to decide rounds that were indecisive to all but those armed with a pen, paper and power. If a fight is close, treat it as such. No good can come from trying to separate the inseparable. Bravery should be witnessed only in the fighters, not the judges.

Rematch riches

For some reason, the sport of boxing finds it easier to call a draw a draw. Indeed, some of boxing’s most famous draws have set up sequels, trilogies and even quadrilogies. Case in point, if the judges didn’t reward Juan Manuel Marquez’ comeback against Manny Pacquiao in 2004, it’s unlikely we would have seen them go on to battle a further three times. Their draw reflected the competitive nature of the first clash and then foreshadowed each one after that.

Even the more controversial draws, such as the one between Lennox Lewis and Evander Holyfield in 1999, only lead to additional blockbusters and more money for the fighters and promoters. Draws generate intrigue, you see, they get people talking in bars, and more than anything else, they essentially act as a binding contract for another go-round. This is perhaps why boxing encourages rather than discourages them. So what if a main event ends all square? Bring on the money-spinning rematch.

Granted, nobody does robberies quite like boxing – there have been a laundry list of stinkers over the years – but now and then a draw offers a safety net. It allows the judges and the fighters to reassess. And a second chance is better than no chance, especially in the UFC, when fighters start fearing the swinging axe once consecutive defeats find a home on their record.

This is high-stakes stuff and, when leaving a fight in the hands of the judges, a fighter is basically saying, ‘Here, go decide my fate.’ There is a huge element of trust involved, but nothing to stop the three men calling a fight wrong. It happens. They are, after all, only human. But still, think of the damage.

Recently Carlos Condit lost a decision to Johny Hendricks in a brilliant UFC 158 co-main event. The fight was as close as could be yet the final decision was unanimous. Some fans and critics felt Condit had done enough to win yet the decision against him was unanimous. Not even a split or majority decision, a unanimous one.

The fight was also an eliminator for the UFC 170lb title, and so Hendricks, the beneficiary of any doubt, would likely go on to fight for the championship by the end of the year. Condit, on the other hand, was left to rue his luck and figure out where to go next.

Now, ask yourself, would it really have been that much of a travesty to see those two share a draw and do it all over again? At least then we’d get to see a repeat of a barnburner and the two fighters would be able to figure out who truly is the number-one contender. Ask yourself this, as of right now, despite watching their first fight, who do you feel is the better mixed martial artist?

Hendricks got the takedowns, as expected, but did he do enough to win rounds purely on that basis? Or do you give credit to Condit for climbing to his feet each and every time he was felled? Who won the striking battle? Hendricks came out hard and fast in the early going, but then Condit seemed to find joy with his pace and better technique as the fight wore on. Which way do you lean in a fight like that? Yes, it’s all subjective, but these are the decisions judges have to make time and time again.

You often hear pundits say ‘nobody deserves to lose’ at the conclusion of a fight and never was this sentiment truer than when Hendricks and Condit embraced after the final klaxon. Yet history told us one of them would likely lose, no matter how close the rounds were or how competitive the fight as a whole ended up being. And so it proved. The judges’ obsession with calling a winner in each and every round conspired to throw up a unanimous decision. Condit, for all his efforts, walked away empty-handed while Hendricks walked into a title shot.

This point is not intended as a knock on Hendricks – he’s as deserving of a title shot as any contender in the UFC right now – more a reflection of how even the closest of fights can end up being deemed one-sided, at least according to the scorecards. Whatever you think, there was certainly nothing unanimous about Hendricks’ win over Condit.

You could also say the same about the 2011 blockbuster between Dan Henderson and Mauricio ‘Shogun’ Rua. A bona fide classic for a reason: this was one of the most thrilling and competitive brawls in UFC history, featuring much in the way of ebb-and-flow action and momentum shifts. Irrespective of this, Henderson was called the winner by unanimous decision after five rounds.

Again, to call either man a unanimous decision winner is to do a disservice to such a hard-fought battle. Why did this happen? Well, look no further than the judges’ fascination with picking one side over the other in every single round. There’s an inherent fear of the fence and it’s costing fighters a realistic and fair assessment of their performance.

Changing the rules

Thanks to the brilliant website mmadecisions.com, Fighters Only discovered there have been 869 decisions so far rendered inside the Octagon since the UFC’s humble beginnings. Some were unanimous, some were majority and some were split. However, only 15 of those decisions were draws. This means, on average, just one in 58 UFC bouts ends up all square!

Given that all of these fights are two-horse races, predominantly fought over just three rounds and featuring exponents of similar skill level, this is quite the revelation. It shines a bright, blinding light on the judges’ reluctance to score rounds and fights even.

What’s more, according to the site, there have been only 22 instances of 10-10 scorecards being handed in at the end of rounds in UFC fights. Meaning that among the thousands of rounds that have taken place inside the Octagon over the years, just 22 were considered close enough to warrant a draw... You don’t need FO to point out the flawed logic there.

Of those 22 level rounds, former UFC commissioner Jeff Blatnick was responsible for providing more of them than any other judge. In fact, before his tragic passing last October, Blatnick showed a greater willingness to score 10-10 rounds than all his peers. But why him? A 1984 Olympic gold medalist in Greco-Roman wrestling, Blatnick not only served as a UFC commentator from UFC 4 to UFC 32 but he also played a pivotal role in helping the UFC get regulated by athletic commissions. During this time he was also involved in the development of the modern rules of the sport, the Unified Rules. And with the help of referee John McCarthy and UFC matchmaker Joe Silva, Blatnick created a manual of policies, procedures, codes of conduct and rules, many of which still exist to this day. In short, he wrote the rulebook. Alas, if he believed 10-10 rounds should exist and be implemented, who are we to argue?

‘There has to be a winner and a loser’ is something a parent might say to their child when they miss out on their first trophy at sports day. It is a sobering slice of reality disguised in the form of a pick-me-up. It is also motivational spiel that professional athletes use to drive themselves, to ensure they are the winner and not the loser and that the reality of this situation doesn’t come back to bite them, as it perhaps did in their younger days. Rest assured, nobody wants to lose.

Nowadays, however, it’s as if this same adage plays on the mind of judges on fight night. They feel responsible for telling a clear and decisive narrative and removing all potential confusion, both in the heads of the fighters and the spectators, who boo loudly whenever their story is ruined by pesky plot holes, namely draws.

But we here at Fighters Only would much rather see a case thrown out of court on the grounds of insufficient evidence, than be subjected to witnessing a rash decision made just to keep the people happy. Evidence is surely all a fight ever is, and if the evidence isn’t substantial or clear enough, then the fighters and fans deserve a re-trial.

Case closed.

Brad Pickett, UFC bantamweight contender

Eight career decisions: four unanimous, three majority, one split

I believe there aren’t enough 10-10 rounds scored and there aren’t enough 10-8 rounds scored, either. Sometimes when I watch a fight I have no idea who won a certain round. I actually want to see how the whole fight plays out before I decide individual rounds. At least then I’d be able to determine how decisive a certain round would be before I scored it 10-9, 10-8 or 10-10. Sometimes it helps to have the bigger picture.

The fights that are hardest to score are the ones where someone nicks a couple of rounds and then gets dominated in the third. Now, do you give the decision to the guy who nicked the first two or the guy who dominated the last? If all rounds are scored 10-9, the guy who started brightly wins the fight. But if rounds are scored more accurately, then you could have a 10-10 in the first two rounds or even a 10-8 in the third. That gives you a better overview of the fight.

In my fight against Alex Owen it seemed to me that I won the first two rounds and then he won the third. But he won the third by taking my back for the entire round. Because of that, I wouldn’t have argued if they gave him the final round by a 10-8 score and then gave me the first two rounds by 10-9 scores. That would have made it a draw. In the end, though, he squeaked by on a majority decision.

As a fighter you start to think about the judges and think about what they might be looking for in the fight. Are they scoring takedowns or are they scoring takedown defense? Do I force the action on my feet or do I look to go to the ground? If it’s a close round, a takedown might win it for me. Is that what they want me to do? I never really thought like this in my career before, but now you kind of have to, especially when competing at the top level.

It’s hard to put people away in fights against the best, so you always have to be wary of pleasing the judges.

Pat Barry, UFC heavyweight

One decision: one unanimous

I hate 10-10 rounds, but I would definitely like to see more 10-8 rounds, which would lend itself towards the possibility of more draws. However, a fight should never be left as a draw. Because of the type of fighter I am, if I win by decision then something has gone wrong.

Fights are supposed to be finished, so if it comes down to the judges then the fighters didn’t do something right. If a fight goes the distance, and it is a draw, then you should just keep fighting until there is a defined winner.

Ben Askren, Bellator welterweight champion

Six career decisions: five unanimous, one split

In some rounds you barely know who the winner is, but you’ve got to give a 10-9 because judges can’t give a 10-10 in that round. I definitely think 10-8s and 10-7s could be utilized to make MMA scoring much more clear. Especially in those fights where there’s one guy who absolutely destroys another guy for one round, then in the last two rounds the other guy narrowly wins.

If his damage is properly scored and gets something like a 10-7 whilst the other guy gets two 10-9 rounds afterwards, then the guy who did the most damage in the first round would win the fight and that’s how it should be scored. When we’re talking MMA, the only time you can get a 10-8 is if someone gets like three knockdowns, and in boxing that would be something like a 10-7 or a 10-6 round.

...