Issue 027

July 2007

For anyone who skipped Sunday school, that's from the Book of Genesis, chapter 32, verses 24 and 25. Yep, wrestling is so old it's in the Bible. No other martial art can match wrestling for its venerable history and the diversity of its many permutations. While fighters like Matt Hughes and Randy Couture helped establish the importance of Freestyle and Greco-Roman styles to a well-rounded MMA game, one form of wrestling has a singular place in martial arts history for its battle-tested efficiency - Catch-as-Catch-Can.

No Holds Barred

Catch-as-Catch-Can (or Catch wrestling) was one of the many forms of wrestling developed in the UK and Ireland, along with the Cornish, Devonshire and Collar- and-Elbow styles to name but three. Catch was peculiar to Lancashire, where it was practiced by the coal miners who settled their differences by wrestling until either a man was pinned or he submitted when caught in a painful hold. Before long, the more skilled miners found they could supplement their wages by betting on themselves; and the need to decisively end a match only increased their interest in submission holds that left no room for debate, unlike pinfalls (pinning the shoulders to the ground) that could be ignored by a biased referee. As the name suggests, Catch wrestlers would take any hold available to them and find a way to turn it to their advantage.

The sport spread to the US with the working men who immigrated in search of better lives. In the early days, many contests were reminiscent of early Vale Tudo events like the first UFC and IVC tournaments. An intercontinental clash took place in June 1887, when Tom Connors, from Wigan in Lancashire, fought Evan Lewis, born in Wisconsin, under Catch rules in Pittsburgh. It was a bloody affair, full of head butts, dirty boxing, and strangles which was eventually won by Connors when he was awarded the decisive fall due to Lewis illegally using his fingers to crush Connors' windpipe. Of the three falls in the match, only one was achieved by actual wrestling when Connors pinned Lewis; the other two were both penalties given to the victim of foul tactics. Right from the start, when Catch wrestlers fought, they left blood on the mat. They coined the phrase no-holds-barred and they meant it.

Mixed Martial Arts at the Turn of the Century

The prize in the Connors-Lewis match, aside from the title of the Championship of America, was $1,000 plus a hefty cut from the ticket sales. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries professional wrestling was hugely popular in the US. Matches took various forms; 'mixed matches' were fought using different rules for each round, for example the first fall would be contested using Catch rules, the second Cornish wrestling and the third by Greco-Roman.

However, Catch was far the most popular. Wrestling matches were a regular attraction at social events throughout the rural United States. Whenever there was a county fair, a travelling carnival or even a town picnic, there would be wrestling It was common practice for the masters of Catch, including Farmer Burns and his star pupil Frank Gotch, to show up at local events using an assumed name and challenge the hometown champion. The townsfolk, oblivious to the true identity of the stranger, always bet heavily on their local boy, who would invariably end up crying uncle when manhandled by the out-of-town wrestler, leaving the ringer to go home with pockets overflowing This practice was called barnstorming and many of the old-timers made their living this way.

By the 1920s Catch wrestling was on the decline as professional wrestling matches were invariably 'worked, with pre-determined outcomes, as opposed to authentic 'shoot' matches. Some Catch proponents kept plying their trade on the carnival circuit or by acting as protectors for the pro wrestling champions. John Pesek, a feared Catch master, (or "hooker) known for his ferocity and ability to break limbs with his submission holds, was the 'policeman' for Ed 'Strangler' Lewis. While Lewis was an accomplished hooker himself, in order to prevent any possibility of some upstart stealing the title from Lewis and his backers, any challenger had to get past Pesek first. No one ever did. Marin Plestina, a 230lb beefcake, was clamouring for a shot at Lewis, so he was matched with Pesek in New York on October 14th, 1921. It was more a Vale Tudo match than a wrestling contest as Pesek, who was almost forty pounds lighter than his opponent, gave Plestina a terrible beating using means both fair and foul. He neck-cranked him with a face bar, cut him with head butts, kicked and punched the unfortunate Plestina until eventually Pesek was disqualified and banned from ever wrestling in New York again. Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised that New York still hasn't sanctioned MMA after witnessing Pesek in action. Plestina went on to become a 'trust' wrestler, working in fixed matches and doing what he was told. A similar fate awaited Nat Pendleton, winner of the silver medal for Greco-Roman wrestling at the 1920 Olympics. He fought Pesek in January 1923 and after thirty minutes of grappling, Pesek cranked on a toehold so hard that there was a loud snap and Pendleton cried out for him to stop.

Catch-as-Catch-Can survived on the carnival circuit for a little longer, but by the 1960s the carnivals had stopped their 'athletic shows' and Catch in the United States was practically a lost art. Back in the UK, a talented grappler called Billy Riley opened his own gym in his hometown of Wigan, teaching the Lancashire style. The Snake Pit was a shabby shed with conditions that would have made a Spartan wince. Never mind showers, there wasn't even a toilet. Riley wasn't interested in softness, he trained hard men to fight hard. One of his students was Karl Istaz, who had represented Belgium at both Freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling in the 1948 Olympics. After training with Riley, Istaz started wrestling professionally in Europe and then the USA. In 1961 he began using the name Karl Gotch, in honour of the famous Catch master Frank Gotch. Karl enjoyed a modestly successful career in America, before accepting an invitation to wrestle in Japan.

The Japanese Connection

There is a long, albeit often antagonistic, history between Japan and Catch wrestling. In the early 1900s, there was enormous interest in the West in Japanese martial arts, fostered by a group of fighters from Japan who, in practice if not in name, went barnstorming across the world. In London, Yukio Tani took on all-comers as a music-hall performer, offering a cash prize to anyone who could last fifteen minutes with him. Tani was a classic barnstormer, weighing less than 130 pounds he looked like a pushover, but he was a skilled submission grappler and only has one recorded defeat on the stage, against his countryman Taro Miyake. Tani even defeated Lancashire's Jem Mellor in a catch rules contest, winning by two falls to one.

On the other side of the Atlantic, four judoka toured the US giving demonstrations and challenging the domestic wrestlers. They were Akitaro Ono, Nobushiro Satake, Tokuguro Ito and Mitsuyo Maeda. Ono had some success against wrestlers using gi-chokes, which at first most wrestlers did not know how to defend. On September 15th, 1905, Ono met Catch wrestler Charles Olsen in what was advertised as a 'blood match', meaning there were no holds barred, and Olsen really let the Japanese fighter have a taste of every trick in his book. Ono managed to execute several throws, but was unable to pin or submit Olsen, who head butted his opponent until Ono's eyes were swollen shut and then broke several of Ono's fingers for good measure. After fighting for over an hour, the battered Ono conceded the contest.

Mitsuyo Maeda met with greater success when he beat Sam Murbarger by two falls to one in a mixed styles match, with two rounds fought using jiu-jitsu rules and one using Catch. The following year Ono toured England, offering £100 to anyone who could survive ten minutes with him. Maeda continued his travels, giving jiu-jitsu demonstrations and wrestling professionally, passing through Europe where he called himself Conde Koma, before he arrived in Brazil in December 1915. For some time, the official Gracie storyline was that Maeda / Koma was either an ambassador or representative of the Japanese government, but in reality he was a barnstormer who went to Brazil to make some money putting on shows and wrestling local challengers. It's not hard to trace the connection between Maeda's style of jiu-jitsu and Catch wrestling. Ono passed away in 1921, and Maeda died in 1941, closing the first chapter in the jiu-jitsu versus Catch wrestling history.

After the initial competition between Catch and jiu-jitsu, people started cross-training. In 1927 Earle Liederman published his grappling manual 'The Science of Wrestling and the Art of Jiu-Jitsu'. In the introduction to the jiu-jitsu chapter, the author noted "There are certain holds in Jiu-Jitsu that resemble the Catch-as-Catch-Can style. If you wish to develop speed of the highest degree, I suggest you take up this style of wrestling." Interestingly, the jiu-jitsu section focuses entirely on standing techniques for self-defence, while the catch techniques bear more resemblance to Brazilian jiu-jitsu and modern submission wrestling. Liederman demonstrates numerous permutations on the double wristlock, a technique akin to the kimura, and the arm scissors, which is a variation on the arm bar commonly seen in BJJ and MMA.

The Rebirth of Catch-as-Catch-Can

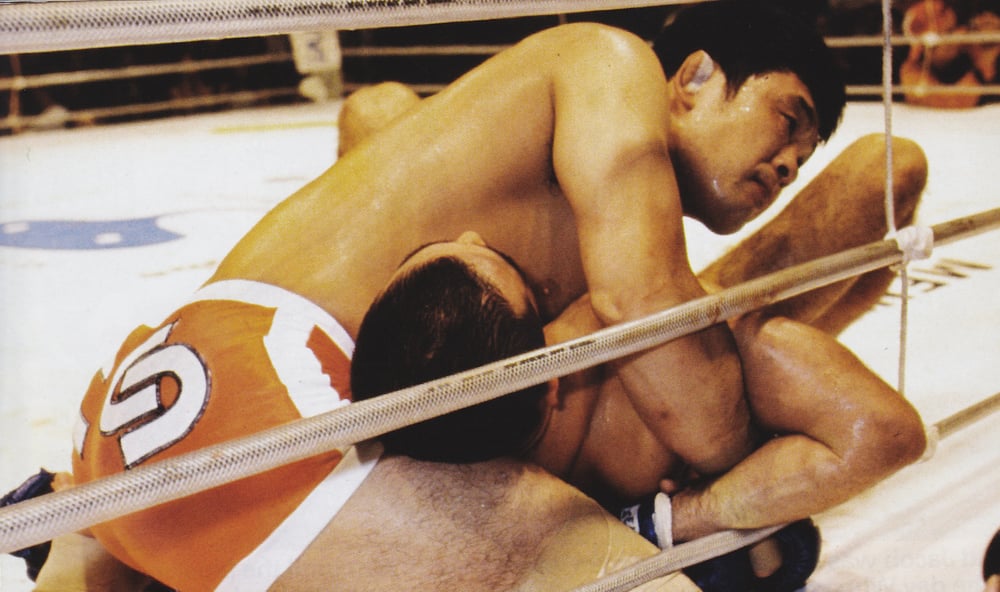

Catch wrestling took root in Japan in the 1970s, when Karl Gotch taught his Lancashire techniques to a group of students including Antonio Inoki and Tatsumi Fujinami, both of whom became major players in Japanese pro wrestling. Working alongside Istaz was Billy Robinson, another graduate of Billy Riley's Snake Pit, and the pair set up the Universal Wrestling Federation and Robinson established his own UWF Snake Pit. Robinson trained both Kazushi Sakuraba and Josh Barnett, while Inoki in turn trained Nobuhiko Takada and Kazuyuki Fujita, although none of them would have the impact on the development of Mixed Martial Arts that Robinson's pupil Sakuraba had.

From his UFC debut in 1997 until his loss to Wanderlei Silva in 2001, Sakuraba turned MMA on its head, dazzling fans and baffling opponents with his unorthodox techniques. Weighing less than 185 pounds, Sakuraba beat opponents who outweighed him by anything from twenty pounds to sixty pounds in the case of Marcus Silveira. Sakuraba's victories over numerous Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu stylists, including four of the Gracie clan, cemented his reputation as a masterful grappler, and many of the tricks in his arsenal came directly from Catch-as-Catch-Can. The move that won the fight against Renzo Gracie, and also broke Renzo's arm, is often described as a kimura, but it would be more properly described as a double wristlock: a staple Catch technique that John Pesek referred to as his 'bread and butter' move. Unlike the kimura, which is performed on the floor, the double wristlock starts while standing, and, aside from the painful submission, the technique simultaneously pins the opponent- a sure sign of its Catch lineage.

Barnett, in turn, won the UFC heavyweight championship from Randy Couture in 2002, then went on to a successful career in Pride. He caught Mark Hunt with a double wristlock and tapped out judo champion Pawel Nastula with a toehold executed without regard for having a secure position in true Catch-as-Catch-Can style. Alongside high-profile fighters like Sakuraba and Barnett, new instructors like Mark Hatmaker and Tony Cecchine have helped revitalise Catch wrestling, and, slowly but surely, the art is reclaiming its place as one of the premier combat systems in modern Mixed Martial Arts..

...