Issue 200

December 2023

The fall and rise of the world's biggest sports franchise. What a long, strange trip it's been, but it shows no sign of stopping.

The UFC. Three letters. Thirty years. The biggest sports franchise on earth. Worth four and a half billion dollars seven years ago, and growing.

Their television deal with ESPN, worth $1.5 billion, comes to an end this year, and another lucrative deal is almost certain to follow. Remarkable.

Remarkable that an idea, just an idea, became an event, grew legs, and then ran away with itself. But there were so many twists along the way, so many moments of luck. The right thing at the right time for the right audience, sharpened and developed, time after time.

But for it all to come together as it has, the right people with the right passion had to meet, give their lives to it, and steer a belief system. And they did, proving that human beings – or at least a significant number of them – want to see gladiators at work and be sold their stories.

“I’m a great believer in luck and I find the harder I work, the more I have of it,” said Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the USA. Thus it has been with the UFC.

Founded on a field of dreams, it has been carefully nurtured over two and a half decades.

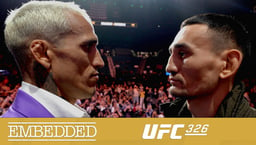

Founded by Art Davie, Rorion Gracie, Bob Meyrowitz, and Campbell McLaren, with creative input from Conan The Barbarian director John Milius, the UFC was a grainy, raw-edged entity on its debut in Denver, Colorado on November 12 1993 at the McNichols Sports Arena, witnessed by 1,500 spectators. Eight men, tournament format, every combat discipline. Best against the best.

No one could have foreseen that night that it would become a juggernaut in the global sports landscape. But its founders knew they had discovered something revolutionary.

The rise of the UFC has been so much about serendipity, the authors of its growth picking up the baton and running their leg of the race with all they have, like the very best fighters the organization has produced and platformed.

If Rorion Gracie’s plane ticket had not been stolen while on a month’s vacation in the USA in 1969, he would not have stayed in America for an entire year as a teenager. Yet those twelve months convinced him of his mission to establish jiu-jitsu there.

Gracie returned to the USA in 1978 after graduating from Law School. Among his students was John Milius, who had just directed the classic surf movie, Big Wednesday, and Gracie, at the time, was hosting challenge matches in his garage. Just fun, just friends.

One of the founding fathers of the UFC, Rorion explains: “We started discussing the possibility of coming up with a different type of arena that would be different to regular boxing matches because I’ve participated in no-holds-barred fighting myself within a boxing ring, and when a guy starts getting in trouble, he slips out of the ring and between the ropes. I’ve seen enough of those in 85 years of jiu-jitsu.”

"So John Milius and I are discussing this at Sony Studios one day. We thought of a moat with alligators. We thought of an arena with sharks around. We thought of an electric fence. Then we said we can’t do that because if the guy pushes the other guy into the moat he gets chewed up. We laughed at it, but in Hollywood your mind travels, and we just thought of every different possibility.”

They were also influenced by the Mel Gibson movie Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. “I wrote a business plan explaining the concept of this new tournament between different styles of martial artists,” Gracie recalls. “At that time there was a video game called Mortal Kombat which was very popular. Fighters from different parts of the world fighting in different scenes of the world. So we explained our deal as Mortal Kombat. But for real.”

Speaking to Gracie all these years later, the passion is still there. So much so that he even emails sketches of the type of arena they were discussing. Big John McCarthy, a student of Gracie’s and sergeant in the LAPD, was signed up as the first referee. Up steps Royce Gracie. And the fight world is silenced.

“The first UFC happened. Now the world is saying what the heck is this? Everybody’s shocked. Royce wins. Everyone is saying ‘Who is this little guy from Brazil who isn’t punching anybody, not getting hurt, and choking everybody out?”

There was an immediate impact in the USA, recalls Rorion. “After the very first UFC, the US Army calls me up. ‘Mr. Gracie, we saw the little guy defeat all the big guys, we need to learn this. They asked me to create a program for the Army and we created a specific course for the US Army that now has been adopted by the FBI, the Secret Service, the DEA – every major federal law enforcement leader in the country has now adopted Gracie Jiu-Jitsu as part of their combat program.

“The Marines implemented it,” he continues. “They did so in such a heavy way that the belts of their uniforms, the little canvas belt, you know what I’m talking about, the belts of their uniforms reflect their ranking in jiu-jitsu.”

The first show sold to 85,000 homes even though their projection was 40,000. The second event was 120,000. It was a sign. By the fourth show, there were 250,000 viewers, but there was a catastrophe. “We had a two-hour pay-per-view window for the airing of the show. In the first three shows, we did it exactly within the two hours. On UFC four Royce was fighting Dan Severn and the show ran to two hours and three minutes. What that means is that everybody who was at home who paid twenty bucks to see the show didn’t see the final move where Royce chokes out Dan, a triangle choke with his leg. Imagine the World Cup final and five minutes before the game is over the television goes blank. One of the biggest mishaps in pay-per-view history was that event.

“We did lose money on that show. We had to refund a lot of people, we had to play the show again for free, people were sacked, but it just generated a lot of publicity. People thought I’d planned that ending. I had people literally call me up and congratulate me, ‘Rorion, you’re a freaking genius, by causing that tremendous excitement where everybody wanted to see the fight and then you stop before you see the climactic ending.’ I said, Are you crazy? That’s how wild the whole thing was.”

But, says Gracie, his aim had been achieved. As for today, Gracie says that he “could not be happier” about the UFC’s growth.

But it was the next phase, involving Dana White and the Fertitta brothers, a coalition with huge financial clout, vision and relentless drive, which has grown the fight organization into what it has become today.

In April 1995, Art Davie and WOW Promotions had sold their stake in the UFC to Semaphore Entertainment Group, a pioneer company in cutting-edge pay-per-view events. Outside the UFC, it showed events such as Jimmy Connors vs. Martina Navratilova in tennis. They knew that novelty sold.

But the fight league had come to the attention of the US authorities, who really campaigned to close it down. It was seen as too brutal, sending the wrong message. Subsequently, it was banned in 36 US states, forcing it underground. The organization began to flag. Yet in the long game, being forced underground created the workings of what we see in the digital age today, and how far ahead it is in democratized media coverage online. It had a voice that was not mainstream, but never went away.

In January 2001, Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta, operating under the name ZUFFA – an Italian word meaning ‘scuffle’ – acquired the UFC from Semaphore Entertainment Group. It cost them $2 million.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is don’t get involved in something you really don’t know and you really don’t understand,” Lorenzo Fertitta explains. “And that was one of the fears when we bought the UFC. But I was able to overcome that because of my affection for the sport and being a fan.”

What Fertitta did brilliantly, however, was what he learned from his father in the casino business: cater to the consumer. Fertitta took the same philosophy from the casino business into the fight business.

Again, there are moments that influenced the powerful innovator and businessman. It came down to his love of working out, a desire for physicality in his own life.

Perhaps we should thank John Lewis. Lewis, now 53, lost more MMA fights than he won, but if not for him, perhaps Fertitta would never have invested his money in the ailing fight organization. As Fertitta explains, he was “originally introduced to the sport and became a fan through training”.

“There was a guy who lived in Las Vegas and was a UFC fighter – John Lewis – and he was teaching Brazilian jiu-jitsu and Dana knew him and we decided to take a private lesson from him. I was like, ‘Wow, can we schedule another private lesson tomorrow and how many times per week can we do this?’ I have a little bit of OCD where once I get into something I have to know everything about it, and that’s what jiu-jitsu was about, learning every move, every counter-move.”

Fertitta then moved into Muay Thai, and even sparred with Diego Sanchez. “I’m not sure why I did that on that day but I learned that it’s not fun getting punched in the nose. He doesn’t have a neutral speed, it’s full-on.”

But Fertitta was hooked. And the fact that Fertitta had grown up in Las Vegas, the fight capital of the world, meant he knew what he was seeing with the UFC.

“Growing up in Las Vegas, being a fight fan and experiencing every big boxing match ever, I knew the psyche of what a fight fan likes,” says Fertitta. He had grown up in Vegas in a golden age of boxing, involving the likes of Sugar Ray Leonard, Marvin Hagler, Roberto Duran, and then Mike Tyson.

“I was a big fan. When I started thinking about boxing as a business, the thing that really struck me was I couldn’t think of an industry or a business that had generated that much revenue – billions of dollars – yet didn’t have a brand associated with it. Everything was a one-off event.”

But it was a struggle, he admits, in the early days of his ownership. “Early on, I can’t stress enough how we had very much an uphill battle. The UFC was a broken brand. It had very bad connotations associated with it, because when it started there were essentially no rules. Once you get branded as something that is a negative sport or a not-safe sport it’s hard to overcome that.”

Fertitta believes it took four years to turn it around, coinciding with the launch of The Ultimate Fighter.

“The seminal moment was 2005, after we had gone to every network in the US to get our programming on the air. Finally we went to Spike TV and we came up with the concept of The Ultimate Fighter reality show, our way to break through to the American public.”

Crucially, they produced the show themselves. “I think we spent about $10 million and it turned out to be the best thing we ever did because since we paid for it we had all the rights. It was a complete success and it was the most successful show ever on that network. We started to become part of sports culture in the US and we built stars like Tito Ortiz and Randy Couture and that’s really what started to drive the business.”

Looking back, Fertitta sees “too many (mistakes) to remember.” If he had his time again, he would have targeted TV. “We made some major mistakes in marketing with the UFC, not understanding what the DNA of the product was and how we’d get it across to the consumer. I think that if we could do it over again we would have put the weight on the TV from day one. TV was the key to making it successful.”

There is a timeline of success, key aspects to the development of the UFC. It’s easy to look at The Ultimate Fighter now and just pass it by. Once rolling, there were new territories, new ideas, new relationships forged in the fight game. It was down to ambition, marketing and promotion.

They developed the rules, they acquired PRIDE, WEC, Strikeforce, introduced new weight classes, and brought women’s MMA to the fore. Latterly, anti-doping has been enforced more strictly.

Aside from that, they harnessed social media successfully, aggressively pursuing a following for Dana White as the frontman. They innovated. They got the best broadcast deals, and kept executive control of how it was run. Broadcast deals with Fox and ESPN have broken new ground in the last decade and a half, totaling more than $2 billion.

Fertitta believes getting the fighters was key, but the platform for them to entertain was as broad as imaginable because of the company he drove like a sales force.

“Sometimes you’ve got to kind of create your own destiny, if you wait around too long it just never happens and it starts to fester out and that’s where we were with the UFC,” recalls Fertitta of the moments when the organization really got moving.

“I think the biggest thing apart from knowing your product,” he continues, “is that you’ve got to know your consumer and you’ve got to be fanatical about it.”

A vision of the future: The year 2043, the UFC at 50

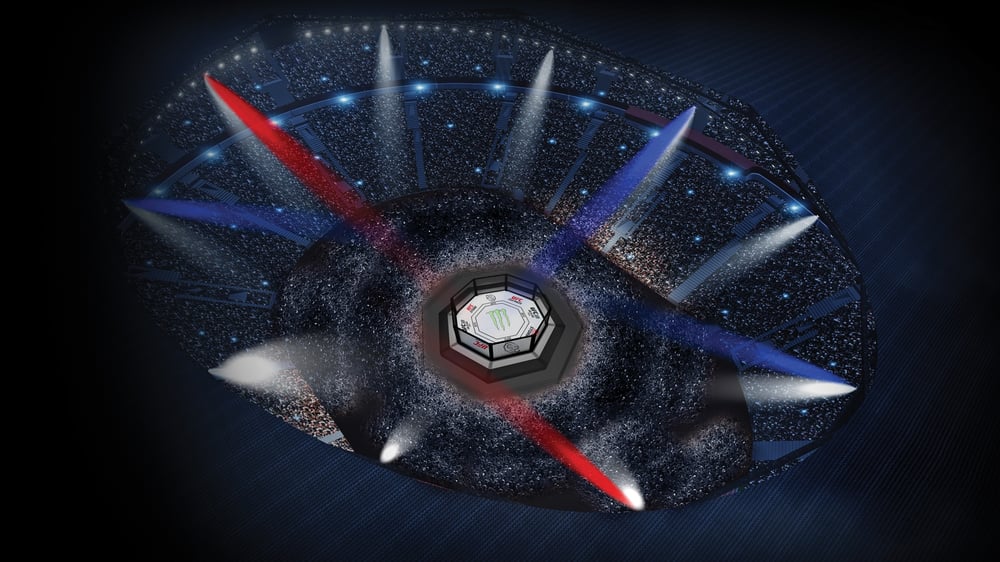

Imagine. The fans scream at each other from their seats inside the state-of-the-art UFC Dome at the north end of the Las Vegas Strip. Ten years old, with a capacity of 50,000, a retractable roof and an Octagon on a huge pulley system that can lift an ongoing fight up and into the arena sky, the high-tech facility also houses community gyms, a small hospital, and parking down six more levels. It has hosted some of the greatest fights in history since it opened in 2033. The year is 2043, and Sin City is still the home of the UFC which is now 50 years old. MMA now rivals football as the biggest sport in the world.

There are two tiers of fight: Pure fights, professional against professional, but every two months the UFC stages a card that features three or four pairings of celebrities facing off in the name of entertainment, as those made famous line their silk pockets with greenbacks.

“So, you want to be a fighter?" yell the fans at the celebrity prelims, a half-decent comedian who is a black belt in jiu-jitsu taking on a musician. Both are performing on The Strip, but here, in a mass of flailing arms, hair, and sweat, they are making even more money.

The serious fights will come later in the night after an intermission when restaurants serving the best organic meals in the world open up for the 50,000 fans. There are screens showing the events sunk into every dining table. Times have changed. African and Chinese male fighters now hold 12 of the 18 world titles in the men’s weight divisions. China now has two million MMA professionals, Africa close to one million. Just getting a title shot for a fighter from East or West Africa, given the purse at stake, will be life-changing. Seventy percent of the champions have emerged from ghettos and slums. The women’s side of the sport now has 10 weight divisions.

The women’s heavyweight title recently drew 3.5 million streaming buys. Maria ‘La Tempesta’ Sanchez, a striking 6-foot-2-inch Mexican-American – who they say has the attitude of women’s pioneer Ronda Rousey, and the same dexterity in her hands as that once had by her namesake Diego Sanchez, winner of the first season of The Ultimate Fighter – is the darling of the sport. Sanchez, 25, won the Olympic super-heavyweight gold at the Rome Olympics in 2040, with the authorities in Italy having allowed combat sports to take place in the ancient Colosseum, especially adapted for the event. Sanchez was the standout women’s fighter at the Games.

Back at the UFC Dome – with the event being streamed live to 20 million phones and personal digital devices – fans are being asked to vote on the plastic panels in their seats. The prelims will be judged by the fans, scoring from the chair pads. The UFC regularly gets 20 million fans streaming the fights.

The venerable Dana White, now 75, raises a hand from Octagonside as the crowd salutes the sports Hall of Famer who retired from active promotional duty five years ago, and for whom a bronze statue has been unveiled on this night in Fight Square, just outside the Dome.

As the title fights get underway, reduced to three-minute rounds for excitement, the venue erupts with noise. In the seats inside the UFC Dome, fans register their votes at the end of the three-minute rounds. Five minutes was changed to three minutes in 2030, because the new generation of fans believed five minutes was too long per round, most of the twentysomethings are watching on their phones. A new champion, from Tanzania, has been crowned.

Then it’s the super-heavyweight title fight. It is a thriller, but over inside a round.

Up steps Conor McGregor, aged 53, into the Octagon. He slips the gold belt, encrusted with diamonds and worth $2 million around the waist of African super-heavyweight champion Abdullah ‘The Bull’ Somali, a 7-foot-2-inch former paramilitary fighter from that country. The Irishman once held the UFC featherweight and lightweight belts, and earned so much money in his pomp, that he was able to buy a stake in the company and is now its frontman due to the retirement of White.

There is a minute’s silence to remember Ken Kim Koo. On this day last year, drug-taking in the sport was suddenly halted with the death of the Korean welterweight fighter, who had lost to an American title challenger who tested positive for banned steroids. An edict was issued declaring that any fighter caught taking steroids will be banned for life.

MMA is in schools, colleges, and the Olympics, and is truly seen as a saving grace for the 40 percent of Americans who have a problem with medicating.

There has been a debate on the Today program about the force of good MMA continues to be. One of those to benefit from a life in MMA is Tim Turbo, who has grown up with both parents medicating, but has gone on to win the Olympics, and now, two years later is challenging for the UFC super-lightweight crown. Its impact has even reached the President of the USA, who is in town and will be in a box upstairs at the UFC Dome. She, POTUS Mrs. Brown, nods and winks at the young American challenger, and says with a twinkle, “See you tonight young man. Good luck in the fight, and make America proud.”

True to his roots, Turbo knows it is about his people, his team, and those who grind it out every day to work out the hurt he feels inside himself that really matters. He knows that fighters are the same throughout the ages. They always have a reason to fight. Nothing changes there. All that changes are the rules, the venues, and the growing audience. He pulls on his gloves and heads out to the Octagon, knowing it will be his night as "Big Balls" by AC/DC accompanies his ring walk… It’s fight time.

Adapted from the original version, “25 years of the UFC,” by Gareth A Davies, originally published in December 2018.

...