Issue 198

June 2023

Mixed martial arts as a sport is still relatively young, and as the sport has developed and grown over the years, so has its profile and success in the United Kingdom.

The history of UK MMA is so rich it would take much more than a single feature to cover the subject in full detail. But, to mark three decades of the sport in the UK, we have revisited the feature first written by Andrew Garvey in 2009.

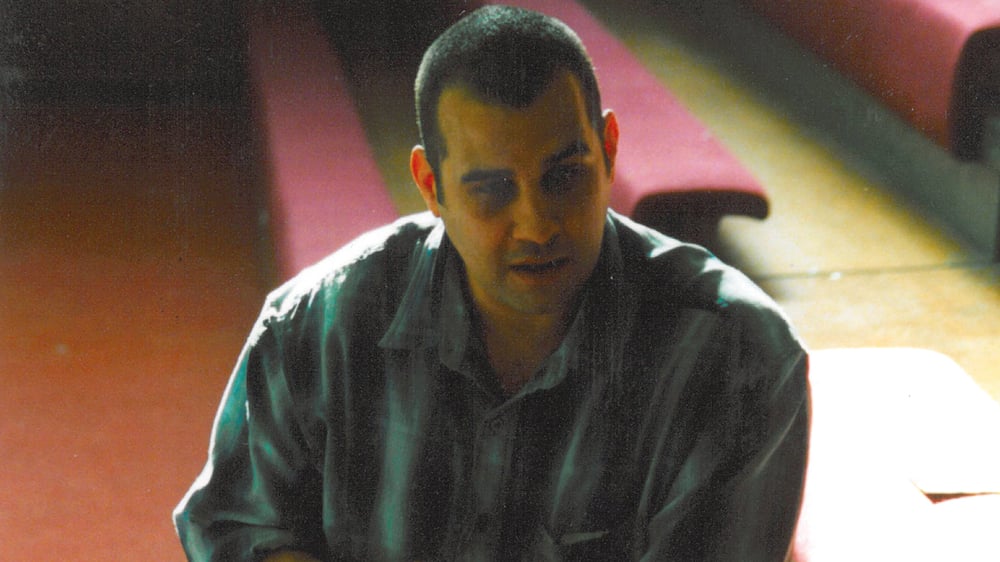

Garvey, along with UK MMA pioneers Ian Freeman, Lee Hasdell, Mark Weir and Alex Reid, told the story of UK MMA in a cover feature from Issue 50 of Fighters Only magazine titled “A brief history of UK MMA,” originally published in June 2009.

Now, nearly 14 years and 145 issues later, Fighters Only’s Simon Head has built upon Garvey’s original work and continued the story from 2009 to present day to give a full timeline of the growth of the sport on this side of the pond.

The dark ages: 1993-1995

Right from the beginning, the pseudo-sport of ‘No Holds Barred’ fighting had at least some presence in the UK. Long before the internet made it easy, VHS copies of UFC, Pancrase and Shooto tapes were available (if you knew where to look), often entering the country via tape traders and spreading from there through further copying. The humble SCART lead used to connect a pair of video recorders deserves some of the credit for introducing the sport to what would quickly become a small, but very appreciative, audience.

Less appreciative were sections of the traditional martial arts and boxing communities, who thundered about the dishonorable barbarism of it all. When they devoted any space at all to the sport, British newspapers lazily parroted the type of nonsense that featured in the US media at the time.

Pioneering UK promoter and fighter Lee Hasdell remembers it well. “I did stories with all the major newspapers and they just twisted things around, made things up about how dangerous it was, lots of malicious lies and petty cheap shots,” he said.

These over-excited journalists were outraged that men were locked in a cage and “forced” to fight, with no rules, no referees and no skill, and implored someone out there to think of the nation’s moral fiber and stop these death fights!

Opponents of the fledgling sport were particularly appalled when MMA shows started actually taking place in Britain, threatening the then-tiny audiences with complete and instantaneous moral disintegration at the sight of two willing participants competing in a sporting event.

Early days: 1996-1999

The first UK MMA shows took place way back in 1996. As pioneering middleweight Mark Weir noted, it was a chaotic, barely organised scene back then. “You didn’t know if you’d be fighting with fingerless gloves or just with boxing gloves on. I fought with boxing gloves a few times and all you could do was kick, box or throw. You couldn’t really do any grappling.

“It was still mixed martial arts because you were using striking and submissions but it was very different to how it is today. Up until, about 1999 or the early 2000s you’d find lots of different rules and you’d just take whatever you could get. I was fighting heavyweights sometimes… a lot of fights had no striking to the head on the ground, more or less like the semi-pro fights you see now. But at that time it was all still developing and changing, even the UFC were putting in new rules and changing all the time.”

Little was reliably or officially recorded in that era and plenty of Britain’s pioneering fighters, like Weir and old rival, actor and television personality Alex Reid have huge gaps and omissions in their “official” fighting records. Reid recalled, “You’d have people going to shows but it was mostly friends and family, nothing like how it is now. We didn’t really view it as something with a future because we didn’t know where it was going. It was a pastime. Before ’98 I’d be paying to fight, paying to enter competitions, it was madness! There was a real lack of technique at that time too, we were way behind the Americans in terms of grappling.”

The first major MMA shows in Britain were the three “Night of the Samurai” events promoted by Hasdell in 1998 and 1999 in a Milton Keynes nightclub. While other UK shows were pulling in tiny audiences, Hasdell said, “We were getting capacity crowds to those shows, 2,500 people. We were pulling in more than kickboxing at the time. That’s why the local council didn’t shut us down. If we were running a show and 50 people were turning up, they could have easily shut us down, but they didn’t want to be killing people’s joy. They’d cover their own arses in case something went wrong, but they wouldn’t shut down something that was that popular. I spent an unbelievable amount of time, so many hours, in meetings with the local council and the police over a period of a couple of years.”

Hasdell noted a few other difficulties with promoting shows in that era. “There’s a lot of things we take for granted now that were very different in the good old days, well, the old days really, because they weren’t all that good!

“I used to have to import gloves from Holland, you couldn’t just go out and buy some. There was no internet, or very little use of the internet. People would be writing me letters asking to fight on shows. Not emails, letters. It would take weeks to sort out some things that are much simpler now.”

The sport was hardly a guaranteed money-maker either. “It cost so much money to run shows, especially when you were bringing fighters over from Japan, even when you had a big gate. I lost £18,000 of my own money on a show once. But generally, you’d make some money here, lose some there. That’s just how it was.”

A new millennium: 2000-2001

In December 1999, Andy Jardine promoted the first Millennium Brawl featuring the ”official” fighting debut of a certain Lee Murray, and a crowd-pleasing main event in which Ian Freeman gave American journeyman Travis Fulton a good pasting in one of the most significant fights in the sport’s very short British history.

Looking back, Freeman explains, “Fulton was supposed to fight Scott Adams (at UFC 24) but broke his hand, so they looked at Fulton’s record and I’d just beaten him, so they invited me in. I’d never left the country before, not even to go on holiday, and suddenly I’m on a plane, on my own, not even any cornermen with me, and met up with Kevin Randleman at the airport. Then I was in the rules meeting with Randleman, Dan Severn and John McCarthy and all these people I’d only ever seen on video before. The whole thing was just surreal.”

Taking a gargantuan leap into the unknown, Freeman was the first Englishman to fight for the UFC. He lost to Adams but fought, and won, two UFC fights later that year. Freeman also blazed a trail for British fighters travelling abroad to seek out the best training partners, something that’s now commonplace. But in those days, with the British scene still somewhat primitive, Freeman’s trips to the US to work with the likes of Pat Miletich and Josh Barnett really helped him stand out from the pack.

With Freeman flying the flag overseas, the UK scene continued growing throughout 2000 and when Millennium Brawl returned for a run of shows in 2001 and 2002, the tiny Judo Centre in High Wycombe they called home became one of the most important venues for MMA in the UK.

At the time, Jardine’s promotion, with ties to well-connected US promoter/manager Monte Cox, a terrifyingly passionate fanbase and regular appearances by the likes of Murray and Weir, was the place to be for British fighters. By the end of 2001, after some superb performances and a string of first-round victories, Weir signed a three-fight deal with the UFC. But “The Wizard” wasn’t the only Englishman the newly Zuffa-owned promotion was eyeing up. Dana White and the Fertittas had their sights set on Britain’s entire, ever-growing, MMA fanbase.

UFC 38 and the rise of UK MMA: 2002

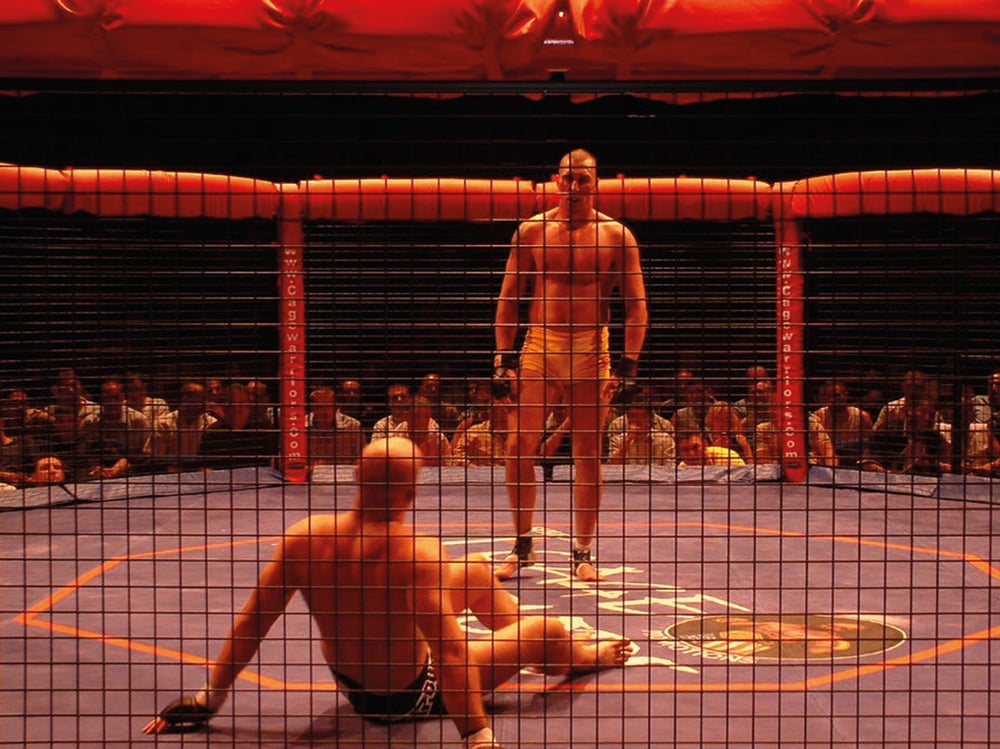

2002 saw enormous changes for MMA in the UK. Promoter Paddy Mooney was first to use a cage for his aptly named Cage Wars promotion, debuting in February. The cage would quickly become one of the most recognisable, common elements of the UK scene, partly due to the UFC coming to the country for the first ever time.

In preparation for July 2002’s UFC 38 in London, American-owned company Zuffa secured a six-month TV deal with Sky Sports for a weekly, one-hour show broadcasting old UFC fights. While that wouldn’t seem like much today, at the time that TV deal was a truly massive breakthrough. The UFC also did their best to educate the media, managing to actually get some positive newspaper stories written alongside the usual, tiresomely predictable rubbish. As Hasdell noted, “When UFC came over in 2002, that put an end to some of the petty media cheap shots. UFC coming over really rubber-stamped it.”

As for UFC 38 itself, it was shown on pay-per-view, drew a little under 4,000 fans to the prestigious Royal Albert Hall, and was by far the biggest, most watched MMA event on UK soil at the time. Weir made his UFC debut, and knocked out durable veteran Eugene Jackson in just 10 seconds. Looking back, Weir saw that show as a massive turning point. “Really it all changed after UFC 38. After that was the first time I had people coming up to me, stopping me in the street, or just when you’d go into a sandwich shop and the guy making the sandwiches would start talking about UFC. And that was before the UFC was as big as it is today. I can’t imagine what it must be like for somebody like Michael Bisping, now it’s really gone through the roof.”

On the night, the UK contingent, all of them genuine pioneers, went 2-2 in the Octagon. Freeman joined Weir in the “Englishmen-with-an-unforgettable-win” category. His crushing beatdown of Frank Mir was the perfect topping to an already amazing evening of MMA action, which also featured fellow hometown heroes James Zikic and Leigh Remedios.

The importance of Freeman’s victory cannot be understated. Though Weir impressed, flash knockouts are quite common in MMA, but Freeman’s sustained assault on the super-slick Mir (who was being groomed for a shot at the heavyweight title) was a statement to viewers around the world: the UK’s fighters are here, and you’d better get used to it.

Having spent (and lost) significant money on their English adventure, the UFC stayed away for almost five years. In their absence, the UK scene went through enormous changes, constantly growing, shifting and evolving.

Constantly growing: 2002-2004

Aside from the new emphasis on the cage (and the widespread pant-wetting excitement of UFC 38), 2002 saw the birth of the new generation of promotions in the UK. March delivered the first Ultimate Combat, while Cage Warriors debuted in July and Cage Rage burst onto the scene in September. Millennium Brawl continued throughout the year before morphing into Extreme Brawl, a name change inspired by the group’s ever-growing links with Cox, promoter of the long-running Extreme Challenge in America’s Midwest.

Just as 2002 brought massive changes, plenty happened in 2003. Network television got its first regular taste of the sport as ITV broadcast 13 episodes of their ‘Caged Combat’ series. Taking a vaguely documentary-style approach, the late-night series of half-hour shows played a significant role in expanding the sport’s fanbase. And exactly one year on from UFC 38, London Shootfighters (by far the most successful MMA gym in the country at the time) made the leap into promotion with their highly ambitious, Extreme Force: Genesis event.

Headlined by Lee Murray’s fight with Jose “Pele” Landi-Jons, it was hyped as the biggest thing to hit UK MMA since the UFC. Sadly, on the night, the line-up bore little relation to the one originally announced and the show apparently lost a significant amount of money, since Extreme Force never returned for a second try.

The boom period: 2005-2006

In 2005 and 2006, the UK scene was dominated by two promotions: Cage Rage and Cage Warriors. Ultimate Combat closed up shop in late 2004, but not before launching the career of one of Britain’s most internationally famous fighters, James “The Colossus” Thompson. Earlier in 2004, the Cage Fighting Championships debuted in Liverpool, running events at the historic Olympia theatre. They stuck around through 2005 and were replaced in 2006 by the still-running Cage Gladiators, ensuring the Olympia its status as one of UK MMA’s longest-running, most regular venues.

Before 2005, the UK scene was widely ignored by the international MMA community, but the expansion of Cage Rage soon changed that. Cage Rage co-promoters Andy Geer and Dave O’Donnell’s enthusiasm for a good scrap (and willingness to pay for big name international talent) ensured that every Cage Rage show in this period was a genuinely big event.

World-class fighters, such as Anderson Silva, Renato “Babalu” Sobral, Matt Lindland, Melvin Manhoef and Vitor “Shaolin” Ribeiro, all made multiple appearances alongside British pioneers such as Freeman, Weir, Remedios and the next generation of rising British stars, such as Brad Pickett and Paul Daley. Cage Rage also made deals with Sky Sports for a delayed highlights show (later to become live broadcasts), had DVDs available in major high-street shops, and forged links with other promotions, most notably Japan’s then-dominant Pride FC.

Freeman noted, “People give him a lot of stick, but Dave O’Donnell, he’s put a lot of money and work into the sport over here and the sport wouldn’t have grown without him and people like him. He should get the praise where it’s due.”

To most MMA fans outside the country, Cage Rage simply was the UK MMA scene but, while the London-based promotion hogged the spotlight, Cage Warriors was building not just the UK scene, but the wider European one, particularly with their ambitious “Strike Force” events.

Featuring a cast of high-quality European talent such as Bendy Casimir, David Baron and David Bielkheden, Cage Warriors also showcased a couple of future UFC stars in Michael Bisping and Dan Hardy. Bisping really made his pre-The Ultimate Fighter name with his electrifying, dominant Cage Warriors fights in Coventry, while Hardy built his reputation for being almost incapable of having a dull fight during his long Cage Warriors run.

Also of note was that 2005 saw the opening of the Wolfslair MMA Academy. Though it was born from its founders’ passion for MMA as their hobby, it soon grew into one of the country’s first fully-kitted, professional training facilities. It didn’t take long for it to attract nearby top talent, including Bisping.

“When I joined the Wolfslair, it came at a very crucial time in my career. I was doing well I had won the Cage Rage belt and I was winning all my fights,” he said. “I needed a lot more help in developing my skills. Just working out in a cage every day, these things are massive. If you don’t train in a cage, you’re at a big disadvantage. When I joined the Wolfslair, I wasn’t looking for them, but I went there and saw the coaches and the facilities and I was blown away. I thought I’d be a fool not to be a part of this.”

The UFC returns and everything changes: 2007-2009

In their near five-year absence, the UFC still maintained a strong UK presence. With TV deals on Bravo and then Setanta, UK fans could watch plenty of the promotion’s events at home, and with the UFC’s triumphant return to these shores in April, they could catch it live, as well.

After years of building up their regional, territorial power bases, no UK promotion had truly established themselves as a national organisation. Cage Rage had the most exposure, but had never even left London. With so many big stars, the brand name in the sport, a media and advertising blitz and a certain TUF 3 winner named Michael Bisping under contract, the UFC easily became UK MMA’s number one national outfit, holding massively successful shows in Manchester, Belfast, London, Newcastle and Birmingham. UFC UK President Marshall Zelaznik explained the reasons behind the UFC’s absence and later return.

“We had success with UFC 38 in 2002, but there was a lot of work to do in the US and, as a company, we felt we had to get that work done in the US before looking to expand elsewhere,” he said. “But the UK was always a major priority for us. The Brits love a good fight, they love the competition, and it was always a no-brainer that the UK would be a major market for us. We knew from our web traffic and TV ratings that we had a good base of fans in the UK, so I came on board in late-2006 to open the UK office in London.”

The UFC’s return to the UK, which was significant as they had quite rightly identified it as prime expansion territory, was based on another vital ingredient: Michael Bisping. Along with spirited brawler Ross Pointon, Bisping was the first Englishman to appear on The Ultimate Fighter. Heavily tipped to blitz the competition in 2006’s TUF 3, Bisping did just that, winning the light-heavyweight portion of the series but also demonstrating the kind of charisma and genuine star power that would soon make him one of the UFC’s most valuable commodities. Broadcast in the UK as well, TUF 3 made Bisping the biggest star in the history of the sport over here.

“How did it feel (to win The Ultimate Fighter)? It felt amazing. I had always wanted to fight on the UFC and I had won The Ultimate Fighter, and then they were using my face on posters launching in the UK,” said Bisping in 2009. “I had to stop and pinch myself, it was amazing. Even now, I’ve fought in the main event twice, co-main event three times. I’m fighting on UFC 100. You can’t do this by yourself; I’ve been fortunate to have a very strong team behind me.”

The return of the UFC has helped bring enormous benefits to the UK scene as a whole. Looking for British talent to help pull in the locals on UK-based shows, plenty of British fighters have found themselves on the fast-track to UFC contracts. Once there, they had to demonstrate they could compete and people such as Paul Taylor, Terry Etim and Paul Kelly more than proved they belonged. The UFC’s excellent PR work also helped to eradicate the media prejudice against the sport. The UFC is now covered as a sport in both the online and print editions of major newspapers like The Sun, The Daily Star and The Telegraph.

The high profile of the UFC, the easy availability of television, DVD, proper media coverage, spectacular live events and home-grown heroes like Bisping have all helped to completely transform the sport’s image and public profile. As Hasdell pointed out, “It’s so big now, it’s everywhere I go. You see people wearing the t-shirts and everybody’s a cage fighter now. Whether they actually are or not, I’m not sure, but that’s what they all seem to say!”

Ian Freeman noted the impact the UFC had on the many other smaller shows that made up the UK scene. “It’s so much bigger now than it used to be, so many more shows. I’m MC’ing about 40 shows a year now. There’s lots of these smaller shows but there’s a really big difference between them and the UFC.” With so many shows, there’s now an outlet for so many more people to compete in the sport, hoping to follow in the footsteps of people like Freeman, Bisping, Etim and the newest fighting superstar to emerge from the UK scene, Dan Hardy.

Along with public demand to see the sport live, these shows were fed by the explosion of MMA gyms up and down the country, training the next generation of fighters at grassroots level. For example, TUF 3 veteran Ross Pointon was just one of many, many people doing their bit. Pointon promoted the first-ever MMA show in his hometown of Stoke-on-Trent, where he ensured positive coverage in the local newspaper and delivered an entertaining event that served to cement MMA’s place on the local sporting scene.

During this time the UK scene also became increasingly well respected at an international level. Top British fighters routinely spent time training in the US, and the development of increasingly professional gyms at home dramatically improved the training opportunities available to aspiring fighters.

The Wolfslair was the most famous example at the time. Top international trainers such as 1990s Brazilian Vale Tudo veteran Mario “Sukata” Neto, quality facilities and the presence of Michael Bisping made it Britain’s most high-profile MMA gym, so much so that it even attracted top international fighters Quinton “Rampage” Jackson and Cheick Kongo into the fold. News that a UFC superstar like “Rampage” was heading to the UK to train would have been dismissed as a ludicrous rumour a few years prior, but it became a reality and offered one more example of how far the UK scene had come.

“The sport is way more mainstream,” said Bisping in 2009. “There are several good magazines out there, with Fighters Only top of the pile obviously! Many websites, clothing brands… You name it, there is a whole lifestyle around it. Obviously there are a lot more people training, a lot more gyms. When I started at the Wolfslair it was the only place of it’s kind. I’d say you could find somewhere to train MMA in every town in the country. The growth has been huge.”

Stirring a sleeping giant: 2010-2015

With the sport starting to build momentum at grassroots level with gyms opening up around the country, more people began switching on to martial arts in general, and mixed martial arts, in particular. While more people were being introduced to the sport on a practical level, the same was happening from a fan perspective.

The UK scene was bolstered by the addition of upstart promotion BAMMA, who hosted live televised big-arena events to offer more opportunity for fighters on UK soil. In 2010, BAMMA 4 produced one of the most-watched UK fights in the sport’s young history as, after a lengthy build-up, Tom “Kong” Watson faced rival Alex Reid for the BAMMA middleweight title. The crowd at the National Indoor Arena was packed to the rafters, with the atmosphere matching that of a big world title fight. “Kong” defeated Reid after five all-action rounds. It was arguably the closest UK MMA got to its own Griffin vs. Bonnar moment at the time.

2010 marked a watershed moment for UK fighters in the world stage, as Dan Hardy became the first UK fighter to challenge for a UFC title when he faced Georges St-Pierre for the welterweight title at UFC 111. “The Outlaw” had compiled a seven-fight win streak, including five successive wins in the Octagon, to book his title shot with GSP, but found the Canadian legend to be just that bit too good on fight night in Newark. Despite his defeat, Hardy had demonstrated that fighters emerging from the UK scene could make it all the way to the highest level of the sport.

The UFC was aware of the growth of the sport in the UK, and launched a special season of The Ultimate Fighter. Titled “The Smashes,” the season pitted teams of fighters from the UK and Australia head to head in a season that eventually produced two world champions in Australian Robert Whittaker, who claimed UFC middleweight gold in 2017, and Brendan Loughnane, who captured PFL featherweight honors in 2022.

This spell also coincided with the rise of Michael Bisping as a legitimate championship contender in the UFC’s middleweight division. He’d been viciously knocked out by Dan Henderson at UFC 100 and written off as a busted flush in some sections of the media. But Bisping, steadfast in his belief that he’d capture UFC gold one day, bounced back and, despite some setbacks along the way, put himself within striking distance of a shot at the title by the end of 2015.

Bisping’s popularity in the UK was sky-high and even united MMA fans north and south of the border, with a capacity crowd at Glasgow’s Hydro cheering Bisping to the rafters as he defeated former title challenger Thales Leites in the summer of 2015. It felt like something big was on the horizon for “The Count,” and MMA fans in the UK were given an early Christmas present when, on Christmas Eve 2015, it was announced that Bisping would face legendary former middleweight champion Anderson Silva in London in February 2016. It would be the biggest fight ever staged on UK soil, and one of the biggest nights for the sport on this side of the pond.

While Bisping was blazing a trail for the UK, a superstar was emerging from Ireland. Conor McGregor had already captured the Cage Warriors featherweight championship in 2012 when he faced Slovakian ace Ivan Buchinger for the promotion’s lightweight title in Dublin on New Year’s Eve the same year.

A thumping counter right hand produced one of the knockouts of 2012 as McGregor flattened Buchinger and became a simultaneous two-division champion. It catapulted McGregor to the UFC, where he’d help take the sport to uncharted levels of popularity, and helped solidify Cage Warriors as a respected and legitimate proving ground for fighters in the UK and Ireland.

With alumni including Bisping and Hardy already competing at the highest level in the UFC, plus the addition of McGregor, the UK-based promotion produced dozens of top-drawer fighters for the UFC, and continues to do so to this day, with a Cage Warriors title often helping to open the door to big opportunities on the world stage. It also shone a spotlight on the promotion’s play-by-play commentator John Gooden, who was later snapped up by the UFC and is now one of the most respected, established broadcast voices for the organization.

The emergence of UK fighters on the world stage wasn’t restricted to the UFC, either. England’s Liam McGeary made history as he became the first Brit to capture championship gold for Bellator when he defeated Emanuel Newton to win the light heavyweight title in February 2015, then defended it seven months later with a first-round submission of Tito Ortiz.

Breaking through on the world stage: 2016-2019

With top talent from the UK scene now gravitating to the sport’s top promotions, the growth of MMA kicked up a gear between 2016 and 2020. Bisping’s bout with Silva at The O2 Arena served up a bout worthy of a Rocky movie, as Bisping fought the fight of his life, and came back from a vicious flying knee knockdown, to defeat “The Spider” and prove what he’d been telling the world for years – that he could defeat the legendary Brazilian.

His next goal was to capture UFC gold, and he did that on a stunning night in California as he sensationally knocked out nemesis Luke Rockhold in the first round at UFC 199 after stepping off a movie set to take an unexpected shot at the gold on just two weeks’ notice. It meant the UK had its first UFC world champion, and Bisping returned home a hero to defend his belt against another former nemesis, Dan Henderson, at UFC 204 in Manchester.

Cage Warriors continued to prosper under the stewardship of Graham Boylan, and struck a strategic win when they sealed a deal for events to be streamed live on UFC Fight Pass. It meant that fans could check out the stars of the future as they climbed the ranks in Cage Warriors, as a steady stream of top talent found its way from Cage Warriors to the UFC.

This period also saw the UK contingent’s strength in depth come to the fore. Rather than one or two fighters competing on the world stage, there were multiple fighters, across multiple weight classes. Fighters were graduating to the big stage and proving themselves, with the likes of Leon Edwards dispelling the stereotype that “Brits can’t wrestle” as he evolved his striking-based skillset to become one of the most well-rounded contenders in the UFC’s talent-stacked welterweight division. He may not have been shouting from the rooftops at the time, but his performances were starting to make people sit up and take notice, and his opportunity would eventually come.

Elsewhere, Darren Till had exploded to the top of the welterweight division and challenged for championship gold, after just seven fights with the UFC. Till’s rise, backed by huge fan support in the UK, saw him defeat Stephen “Wonderboy” Thompson on an electric night at the Echo Arena in Liverpool. His split-decision win earned him a shot at Tyron Woodley and, even though he fell short on the night, it showed that a fighter from the UK could build the sort of momentum to force their way into championship contention.

Beating a pandemic: 2020-2021

Just as the MMA in the UK seemed on the verge of another explosion, the global COVID-19 pandemic struck. The first big-event casualty for the UFC was a March 2020 UFC Fight Night show at The O2, where Edwards was due to face former champ Woodley in a potential title eliminator. But, as the world shut down and entered into enforced lockdown, Edwards’ momentum was slowed to a stop.

As the world got used to living in “COVID bubbles” and employing social distancing, promoters looked for ways to keep the lights on and keep the sport moving. Cage Warriors led the way in the UK, with Graham Boylan establishing five locked-down shows at the BEC Arena Manchester, then repeating the formula for nine more events at iconic London boxing venue the York Hall through 2020 and 2021.

Those events not only showed the desire and commitment to keep UK MMA responsibly moving in the face of a global pandemic, it also helped put Cage Warriors on a platform where MMA-starved fans around the world were switched on to the UK promotion’s events on UFC Fight Pass.

Back in the swing of things: 2022-present day

By 2022, MMA had emerged from the pandemic, and when the UFC decided where to go for its first international show with full-capacity crowds, they chose the UK, with the Octagon heading to The O2 Arena in March. With a stack of UK fighters desperate to get back to action in front of their own fans, the UFC packed the 12-fight card with 10 Brits. It was the chance for UK’s big stars – and the passionate UK fans – to announce their return to the big stage, and boy did they deliver

On an electric night in London, the fighters on show served up nine finishes from the 12 fights, with six of those coming from UK stars as the likes of Tom Aspinall, Arnold Allen, Paddy Pimblett, Molly McCann and Muhammad Mokaev all scored huge stoppage victories in a party atmosphere at The O2. The performances, and the fan reaction, blew away UFC president Dana White, who immediately said he’d tear up his schedule to ensure the Octagon returned to the UK later that year. White was good on his word, with another big show landing at The O2 in September to another jam-packed UK crowd.

Bellator also returned to the UK as London’s Michael “Venom” Page was controversially denied victory in his fight for the vacant interim welterweight title after a split-decision favored opponent Logan Storley at Wembley Arena while, elsewhere, Cage Warriors continued to put on top-quality shows, with their expanded reach seeing them branch out to the United States and Italy as they took the UK brand on the road to San Diego and Rome.

The value of the UK market was further illustrated with the global expansion of the Professional Fighters League, who announced the inception of PFL Europe, with the debut event scheduled to take place on March 25 in Newcastle, and a host of up-and-coming UK talents signed to their European roster.

The second half of the year ended with a double celebration for UK fight fans as we crowned not one, but two world champions.

In August, Leon Edwards lived up his “Rocky” moniker as he produced one of the greatest comebacks in UFC title fight history to spectacularly knock out welterweight champion Kamaru Usman in the last minute of his UFC 278 title challenge. It was an incredible moment for the sport in the UK as Edwards, who steadily built his resume with little fanfare and no manufactured trash-talk, finally got his shot at championship gold and delivered with a stunning head-kick KO for one of the biggest knockouts of the year. And he did it all while training in his home town of Birmingham, at Team Renegade.

Then in November, Manchester’s Brendan Loughnane, spurned two years earlier by UFC president Dana White despite a dominant victory on the Contender Series, captured the $1 million 2022 PFL featherweight championship with a brilliant fourth-round TKO of Bubba Jenkins. Loughnane lost out in the semi-finals the previous season, but came back determined to win the whole thing in 2022 and did so after producing two of the most complete performances seen by a UK fighter on the world stage as he defeated 2021 finalist Chris Wade, then former Brave CF champion Jenkins, to win the 145-pound title and the million-dollar prize.

A little further afield, Sunderland heavyweight Phil De Fries is the most dominant champion in the history of Polish promotion KSW.

The future of UK MMA

It all means that UK MMA is in rude health as we head towards the summer of 2023. UK fighters are battling on equal terms with the world’s elite across each of the world’s top organizations, and there’s a crop of surging contenders looking to gatecrash their respective divisions’ title pictures as the year progresses.

At home, there’s a clear pathway for fighters looking to progress to the UFC, while Bellator and PFL have dedicated European operations that are offering opportunities to UK talent and the chance to progress to the big stage with their respective brands. There’s a fresh crop of talent coming through from the amateur ranks, too. A perfect example of this pathway is Christian Leroy Duncan, who competed for England on the amateur stage before transitioning to the pros with Cage Warriors and capturing their middleweight title. Now he’s signed to the UFC and looking to make waves as the UK’s newest addition to the 185-pound weight class that once had a certain trailblazing Brit as its champion.

It’s never been a better time to be a fan of MMA in the UK, too. UFC is live on BT Sport, Bellator has made BBC iPlayer its home, while PFL has recently inked a deal with DAZN. Fans looking for even more MMA to scratch their itch have the ability to follow the a host of promotions via UFC Fight Pass, while other broadcasters are starting to partner up with other European promotions. French organization Hexagone and Czech-Slovak promotion Oktagon, have signed deals with BT Sport and DAZN, respectively, with Oktagon also preparing to host its first event on UK soil with an event at the Manchester Arena later this year.

If the sport took its baby steps in the UK in the mid-1990s, and went through its growing pains in the early 2000’s, it’s now well and truly grown up and standing on its own two feet in 2023. And, with more opportunity for UK fighters than ever before, and more good-quality MMA available for fans to watch, the future for the sport on this side of the pond is looking bright.

We can’t wait to see what the next 10 years has in store.

...