Issue 200

December 2023

Thirty years ago, fight fans witnessed the genesis of what would become one of the world’s most popular and profitable sports properties, writes Brad Wharton.

Ostensibly devised as a tournament to prove which of the traditionally unmixed martial arts was superior in open combat, in truth the men behind the machine were at crossed purposes.

Rorion Gracie, a member of the now legendary Gracie clan, had brought his family’s style of grappling to the US, finding work as a fight and stunt coordinator in Hollywood, with a lucrative sideline in teaching Jiu Jitsu to the well-heeled Los Angeles in-crowd.

For him, this was a chance to re-educate the world as to the actual mechanics of fighting; a living, breathing infomercial that could expand the Gracie brand on a global scale.

For the other co-founders, like entrepreneur Art Davie and media exec Campbell McLaren, it was an opportunity to cash in on the martial arts boom and build a sport – or at least a spectacle – that would not only prove to be a box office draw, but one that could take advantage of the lucrative home Pay-Per-View market.

The pair were more focused on the bombastic elements of the show. One of the original pitches for the first Ultimate Fighting Championship was a ‘live-action Mortal Kombat’; the gory, parent-bothering arcade sensation taking early 90’s America by storm.

Key to Mortal Kombat’s success was its highly eclectic cast of characters. On that front, UFC 1 had it made. Royce Gracie, the skinny, swarthy, gi-clad representative of grappling’s first family. Ken Shamrock, a walking, talking He-Man action figure fuelled by unbridled rage and testosterone. Teila Tuli, a retired Hawaiian Sumo wrestler who would later find fame in the re-make of Hawaii 5-0, and Gerard Gordeau, the only Dutch kickboxer who’d answered the call.

Nobody really knew how the fights themselves would play out, but with a menagerie of martial artists and ruleset that promised chaos, UFC 1 looked on the surface to be about as Mortal Kombat as something could be, without somebody losing their spine.

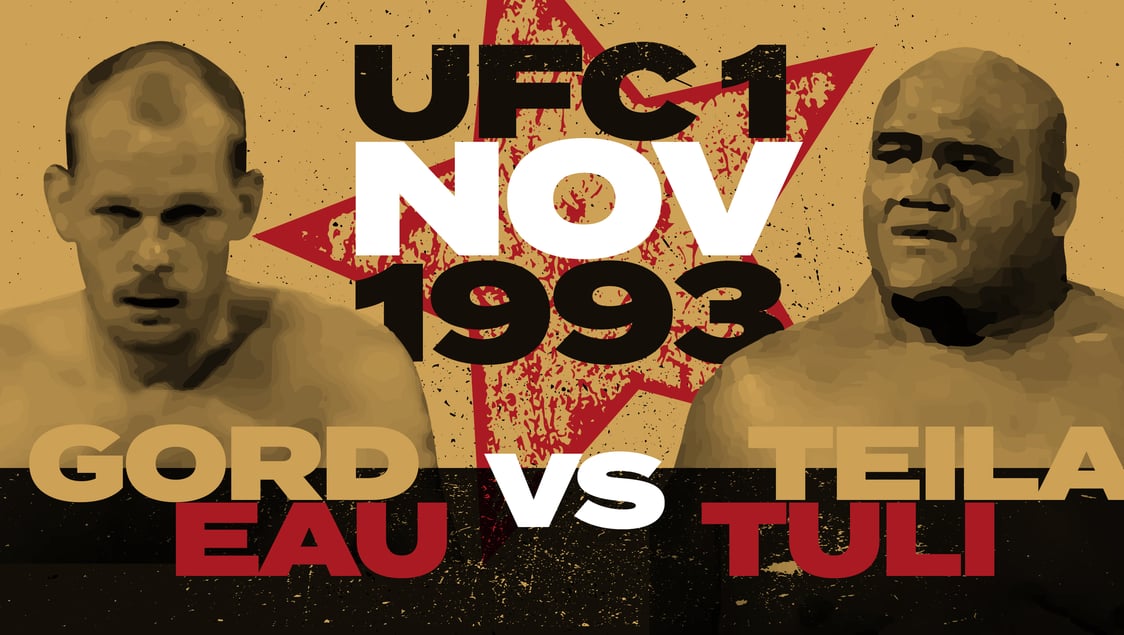

Quarter-Final: Teila Tuli vs. Gerard Gordeau

They say you never get a second chance to make a first impression and, on that basis alone, Davie and McLaren got everything they wanted in UFC 1’s opening bout.

The two combatants couldn’t have looked more different. At six-foot-five and over 200 pounds, Gordeau cut an imposing figure, one that had served him well over a career spent working the doors on the notoriously harsh Dutch nightclub circuit.

Tuli, by contrast, stood a few inches shorter but outweighed him by 200 pounds.

Tattooed (including a Swastika as part of a larger design on his arm) and sporting a close-shaved head, the Dutchman raised eyebrows upon entering the Octagon, delivering what appeared to be the ‘Seig Heil’ Nazi salute to the crowd.

Gordeau would later clarify that this was a traditional Savate (French kickboxing) gesture, his tattoo - inked in Asia – was derivative of Buddhist symbolism and that he himself was of Jewish ancestry.

Regardless, eyebrows had been raised (particularly among the group of media execs invited for a ‘shop window’ cage side experience) before the first bell had even sounded.

When it finally did ring, the action was brief and brutal. Tuli circled around the outside of his opponent before bull-rushing, clattering into the fence and staring up at the lights, defenceless.

The streetfighter’s instinct of not allowing an opponent to get up kicked in for Gordeau, and he lashed out with a brutal roundhouse planted squarely across Tuli’s face.

The Dutchman followed up with a crushing right hand to the eye, cutting the helpless Hawaiian and prompting referee Joao Alberto Barreto to intervene.

…and just like that, it was over.

Confusion reigned in the immediate aftermath; bouts were only supposed to end via corner stoppage, KO or submission, and this had been neither.

Still, it was the blood ‘n’ guts ultraviolence upon which the crowd had been sold, and they were ready for more.

Semi-Final: Royce Gracie vs. Ken Shamrock

Royce Gracie had breezed into the semis after IBC-ranked boxer Art Jimmerson (infamously sporting one glove) submitted following a single light headbutt from mount.

Jimmerson – who had already secured a $20,000 flat fee for entering the competition - had reportedly balked upon seeing the injuries sustained by the first two quarterfinal winners, and wanted no further part of it.

Billed as a ‘shootfighter’, Ken Shamrock was a promoter’s dream. With a body chiseled out of granite, slicked-back hair and a permanent scowl etched onto his face, he looked like something out of an 80s action movie and crucially, the man could scrap.

Ken had found solace from a background littered with abuse, drugs, and violence in the pursuits of sport and fighting; be that amateur wrestling or punching out toughs for quick cash purses in the parking lot of a local bar.

His talents had taken him to Japan’s Pancrase organization; a touring troupe of pro-wrestlers competing in ‘legitimate’ martial arts contests. While many of the early Pancrase bouts were later revealed to be fixed or thrown, they’d given Ken an education in submissions that saw him cruise past kickboxer Pat Smith with a butter-smooth heel hook in his first UFC contest.

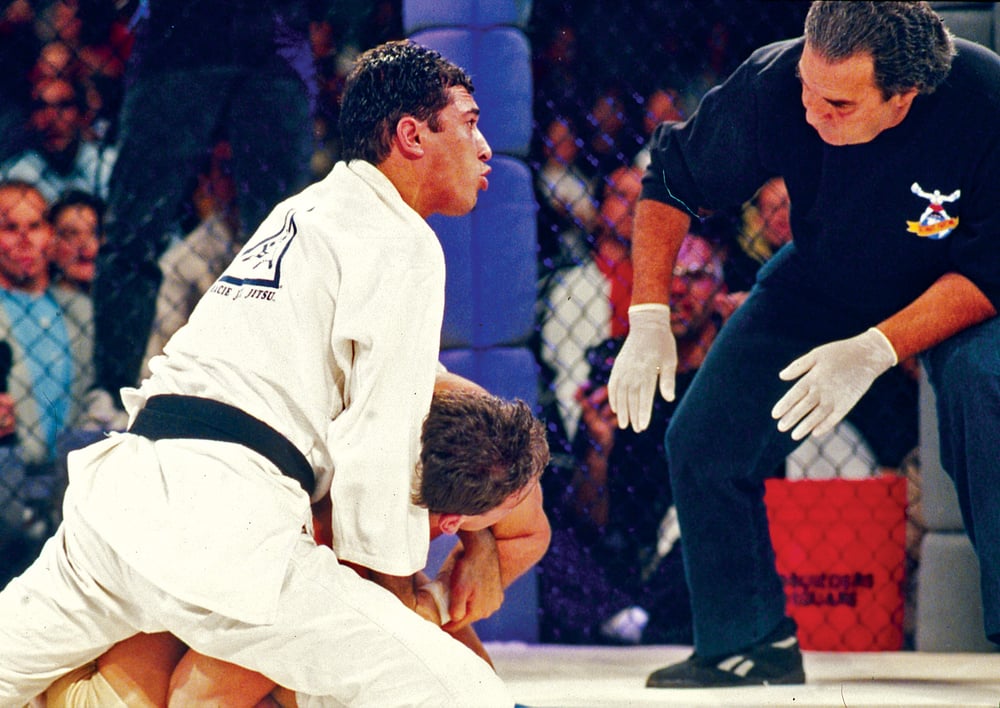

Gracie, though, was a different prospect altogether. While the bigger, stronger, faster Shamrock was able to sprawl on his opponent’s initial takedown before hauling him onto his back, Royce ultimately had his man right where he wanted him.

The smaller man played guard, initially attacking an arm before sweeping and securing the back. Shamrock had been here before, but never against an opponent sporting a Gi.

It would prove to be the difference maker, with Gracie using his jacket to assist in what the commentators called a ‘back choke’ and in doing so, laying the groundwork for what would become one of the sport’s most notorious rivalries.

The Final: Royce Gracie vs. Gerard Gordeau

Gerard Gordeau was in bad shape. The kick he’d wrapped around Teila Tuli’s face in the evening’s opening bout had famously sent one of the Sumo wrestler’s teeth flying out of the cage, and lodged another in his own foot. He’d also badly broken his right hand.

Not wanting to leave Colorado with mere pocket change, he’d jammed his fist into a bucket of ice and took a deep drag of a cigarette while his corner taped the wound on his foot closed, tooth and all.

Later, Gordeau would insist that he was originally penciled in to fight Gracie in the quarterfinals, before the brackets were gerrymandered when the Gracies discovered that he’d competed in ‘shoot-style’ pro-wrestling matches in Japan not dissimilar to Shamrock’s.

While Gordeau may have been tough enough to clobber big, lumbering opponents like Tuli and an out-of-shape Kevin Rosier, he simply didn’t have the technical nous to prevent Gracie from imposing his will.

The Brazilian instigated a clinch followed by a trip takedown that no amount of fence-grabbing from the Dutchman could prevent. A couple of tidy headbutts forced Gordeau to give the back, from where Gracie easily fished out the fight-ending rear naked choke.

With the referee missing the submission in his semi-final against Shamrock, Royce held on for dear life as Gordeau frantically slapped the canvas with both hands.

In just four minutes, fifty-five seconds, and without absorbing a single punch, Royce Gracie had redefined competitive martial arts. But as the lights went down on November 12, 1993, all he cared about was going to Disneyland.

...