Issue 148

December 2016

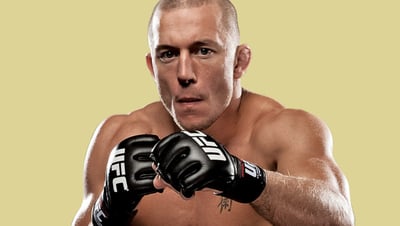

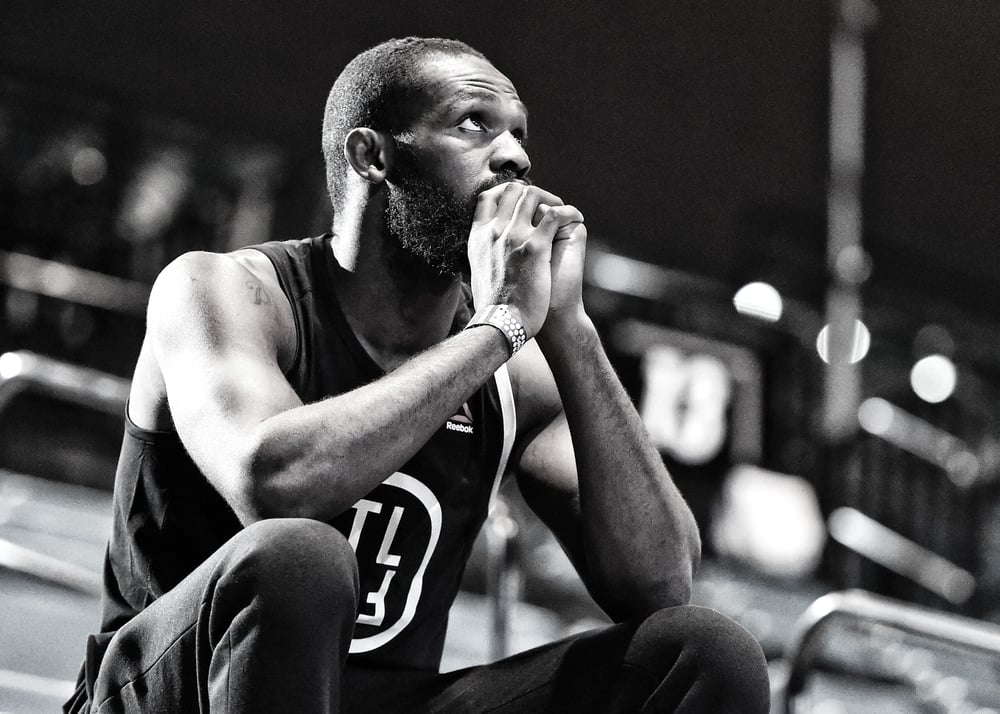

Jon Jones reveals the New York upbringing and family values that sculpted him into the greatest natural talent in MMA – and how those same principles will see him overcome his demons and return to the cage to salvage his legacy.

Jon Jones was destined for greatness. At 23 he was crowned UFC light heavyweight champion. It wasn’t long before he became regarded as the best pound-for-pound fighter in the world. The world was his.

Yet behind the spinning elbows, the crushing submissions and the smile of a man seemingly destined to replace Anderson Silva as the greatest mixed martial artist of all time, Jones’ private life was in turmoil.And it was about to catch up with him. After a run-in with the law and some failed drug tests, he was left out in the MMA wilderness.

2016 has been the toughest of Jon Jones’ career. Yet perhaps the most painful moment is yet to come, when 26 fighters step into the Octagon at UFC 205 in New York City.

Jones, a proud New Yorker, won’t be among them, fulfilling his dream of competing under the iconic Madison Square Garden lights.

Earlier in the summer, Jones tested hot for letrozole and clomiphene ahead of UFC 200, scuppering his opportunity to reclaim his 205lb UFC belt from Daniel Cormier.

How and why the banned estrogen blockers entered Jones’ system is yet to be made public – though a Nevada State Athletic Commission hearing was scheduled for October 10th – but both the fighter and the UFC were making noises suggesting it was accidental.

For Jones to willingly take a banned substance would be out of kilter with the opinions he’s expressed throughout his career.

As an athlete who has regularly spoken out against doping cheats in sports, Jones reiterated his stance against performance enhancers to the producers of The Hurt Business documentary.

“Like in all sports where there are millions of dollars involved, people want to gain an advantage.

"People will do anything they can to be top dog. Obviously, as you age too, people look to find solutions. That’s why we’ve seen TRT and HGH and all that stuff.

“Dan Gable was one of the greatest wrestlers of all time and he said a quote that really resonated with me. ‘Once I found out an opponent had taken steroids then I knew I could beat him because he didn’t have the heart or the mind to go the extra mile.

"He didn’t have that dog in him to become victorious. He found the shortcut.’ And like I say, there is no shortcut to greatness.

'I work my tail off with these chicken legs, but I push these legs to do great things'

“I look at athletes who take steroids as being weak. They could be the strongest guy physically, but they’re weak in the heart and in the mind. If you are competing, I’m totally against it.

“And I do care if guys are taking things and competing. I work my tail off with these chicken legs, but I push these legs to do great things.

"If I can do it, then other people should be able to figure it out too. So for someone to gain an advantage that’s not necessarily earned – that’s offensive to me.”

The former undisputed light heavyweight champion of the UFC was not raised to behave like that. The son of a preacher, Jones and his two brothers – NFL stars Arthur and Chandler – were protected from their environment growing up in New York.

They were pushed towards athletics, kept off the streets by their parents and encouraged to use sport to further their lives rather than allow sport to use them.

“I was born in Rochester, New York. It’s a tough area,” Jones recalls. “I moved away from there in 1998 when I was 10 or 11 – plus my parents kept us pretty sheltered – but it was tough, I remember that. Lots of crime, lots of murders.

“My uncle – my dad’s brother – was shot just around the corner from our house. He actually drove to the front of our house and lay dead in the back seat of a car for three days and we had no clue until his body started to smell. So it was rough.

"My dad got us out of there as quickly as he could.

“We moved to a suburb called Endicott, New York. It’s a real small Italian town and I really consider that my hometown.

"I became the person I am growing up there. I went to high school there, and have a lot of friends that still live there. So I’m a northern New Yorker.”

Jones recalls: “I definitely wasn’t a fighter growing up. I got into a lot of fights with my brothers, but street fights, no. If you look at my face, I’ve got a scar in the middle of my forehead. That’s from my brother. My cheeks, my forehead, I’ve got little scars all over my face but those are from my brothers.

"Growing up we weren’t out thuggin’ or nothing. It was just the usual, ‘Get your feet off me,’ or who plays first on video games. Stuff like that.

“I was kind of a geek in high school. I was skinny, I sang in the jazz choir. I wasn’t popular. I wish I had the confidence from fighting back then. I was just my own guy I guess.

"But fighting has made me bigger than I thought I ever could be. So much good has come my way from martial arts.”

So how does a band geek become the greatest natural talent in fight sports? Well, if it wasn’t for current UFC bantamweight Joe Soto, Bones may never have started fighting at all.

“I attended (Iowa) Central Community College and my freshman year I had a roommate, Joe Soto, and he was all about mixed martial arts. I had never seen it or heard of it,” Jones recounts.

“After wrestling practice, he would start training jiu-jitsu and he’d have guys on his back and tied up in his legs, and he’d be trying to choke them out. It was crazy.

‘It was always in my subconscious. I kind of knew I could make a career out of it’

“I just thought it was bizarre, at first. Then the more I watched it, the more I became a fan of it and I started to really enjoy it. After wrestling then I started doing it. Eventually, I got invited to my first pay-per-view, which was Chuck Liddell vs. Randy Couture.

“I was at a townie party and all these people were so obsessed with what was going on, on the screen. People were looking at Chuck Liddell like he was a god or something. I mean, they were just going crazy for him.

“He won the fight that night and from that night on I always kept martial arts as something to fall back on. It was always in my subconscious. I kind of knew I could make a career out of it.”

Yet it was sometime later before Jones returned to the mats. While struggling to get a career in law enforcement off the ground, Bones worked as a bouncer at a local bar in Endicott and admits he felt like a failure as brothers Arthur and Chandler were paving their way to the NFL by performing on the football field at Syracuse University.

‘People were genuinely mistaking me for a martial artist and yet this was my first practice’

“I kind of felt like I was wasting my talent. I had won nationals at college and I had my associate’s degree, but here I was bouncing.

"But then the strangest thing happened. I had a guy write to me on MySpace, which was like the Twitter of its time, and he says, ‘I see you have as your display picture your hands up and with a UFC hat on. Well, if you want to be an MMA fighter I think that would be a great deal for you. My cousin has a martial arts school that’s about an hour away.’

“I’m reading this and it’s a Saturday night, I’d just gotten home late from the bar.

"So I waited until Monday and I wrote the guy back and was like, ‘Hey, tell me more about your cousin’s school and his gym and everything.’ So he sends me this link to a video of this fight team.

“Now these guys were just borderline amateurs, no technique, just beating the crap out of each another. Just brawlin’. But I was like, this is for me, I can do this. So I started training and commuting to this garage, which is all it was. It had a mat and two heavy bags. But that was my first martial arts school.”

Unsurprisingly, Jones admits he was a natural.

“I remember after my first practice, I’d beaten up one of the heavyweights who had been training for a long time and all the guys were like, ‘So where did you train before this? What’s your martial arts background’ And I was like, ‘I’ve never taken any martial arts classes before, I was a wrestler and I’ve been in lots of fights with my two brothers.’

"They were shocked.

“From that day forward I knew I had a gift. People were genuinely mistaking me for a martial artist and yet this was my very first practice. So I knew if I applied myself I could be a success. Within four months I won my first jiu-jitsu tournament – with four finishes.

‘From that night I wanted to be the best. To make it to the UFC... And nothing has changed’

“My coach back then too was like, ‘You know, I won my first tournament after training for a year, but I didn’t submit anyone. It was all points. The fact you came in after four months and finished everybody – you have a talent, man. You could be a UFC fighter.’

"So he introduced me to a boxing coach, then a Muay Thai coach, and I just ran with it from there.”

That’s an understatement. Jones, despite having zero amateur contests, claimed three stoppage wins over three consecutive weekends in April 2008 to announce his arrival in the sport. He was 6-0 and making his first Octagon walk at UFC 87.

“It just felt like I was back on the wrestling mats,” Jones says when he looks back on the early fights in his career. “I just felt so at home, and I went out there with supreme confidence and I just dominated. I thought it was like the WWE or something. I loved it.

“I remember my pro debut like it was yesterday. I beat him up and played to the crowd a little bit. And I was in love with it (MMA) forever since.

"From that night I wanted to be the best. To make it to the UFC, but also to be successful, to be the best. And nothing has changed.”

Jones’ path to greatness may have taken an unwelcome detour, but every man deserves a fresh chance and Bones’ future is filled with optimism and expectation. It’s time to make up for lost time.

New breed: Real men make girls – who fight

Jon Jones has four daughters and unlike a lot of fighters, he’d love nothing more than if one or all of them turned to fight sports later in life.

While fighters maintain they live the lives they do to provide for their children, Jones insists combat sports have been nothing but positive for his development as an adult and he’d encourage his girls to strap on the gloves if they ever wished.

“I have four daughters. A seven-year-old I had when I was in college, who lives with her mom in Iowa. And a six-year-old, a four-year-old, and a two-year-old who all live with me and my fiancée. And I would love it if any of them wanted to become a professional fighter.

“I know what fighting has done for my life so for them to have that would be great. Fighting has made me a better individual. I wish I had it in high school. Some much good has come my way from martial arts.”

The fans: Empowering 'Bones'

Jones says the love and support of the fans are what keeps him moving forward in the toughest period in his professional life.

The dream of one day walking to the Octagon again and feeling that support is what drives him.

Jones says: “I feel on top of the world right before a fight. When I am in the arena, when I know all these people have traveled from their homes, from overseas, to see me. It empowers me.

"It’s what I am here for. This is my art. It’s my time, my moment, my home. Then I try to take all that energy from the fans, whether they’re booing or cheering. I draw all that power, hold it in and channel it at my opponent.

“I love the fans. I respect them so much. Muhammad Ali once said, ‘Never look down on people who look up to you.’

So even if I don’t have the time, I always try to give them something. Even if it’s just a smile or a wink, I have to give the fans something.”

The future: Landlord, teacher and hero

“I would like to fight until I am 32,” Jones says, when asked about how long he wants to continue fighting, “I’d like to retire before that age.

"I’d like to think I’ll be gone by then, for sure.

“I have lots of plans for when I retire. Ithaca, New York, is where I will retire to. I want to own an apartment building there and rent out to students.

“I’d also like to open a gym. People are paying $50 a month to train martial arts up and down the country with guys where nobody has ever seen fight before. It’s crazy. So I think there’s a real market there for me after I retire.

“If I opened my own academy I know it would be a success. But I’d also like to get into movies – do some acting. I’ve seen a lot of people do it, and I believe I would be good at it. I’d take it very serious – get the best coach I can. One day I’ll make it in Hollywood.”

...