Issue 112

March 2014

Fame, fortune, adulation, being a world champion is the ultimate in competition, but it can't go on forever. Retiring from any sport is tough, but from fight sports perhaps tougher than most, as it's not simply a career choice at the top - it's a way of life, FO investigates why even the greats very rarely walk away on top

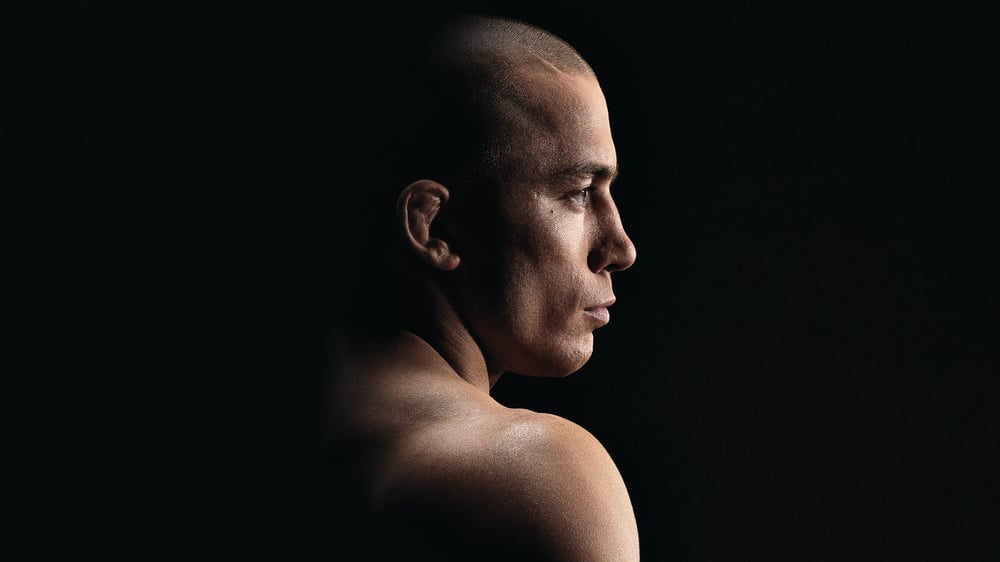

Back in 2009, Georges St Pierre was fresh from a five-round mauling of Thiago Alves and seemingly so dominant that the welterweight rankings, used to determine his next challenger, were essentially redundant. He won fights without losing rounds and had systematically cut open the division to such an extent that the idea of a title shot was something to be feared rather than welcomed.

Yet, despite this dominance, still he walked small, stripped of the arrogance that pollutes most champions boasting similar credentials, and still he remained humble, never once believing his powers were superior to the rest. Moreover, he was incredibly candid for a professional fighter, and while peers choose to puff out their chests and hide behind a shield of bravado, St Pierre projected an honesty that was both refreshing and surprising.

“I didn’t have to do this,” he admitted to me at the time. “I had choices as a kid. I come from Montreal, Canada, and people from my part of the world have lots of choices. I was an educated child with lots of open doors. Despite all that though, I chose to be a mixed martial artist and I set my goal to become UFC world champion.

“I don’t care about fame, I don’t care about people saying how great I am. I’m just being myself and want to please the people that have always believed in me. Money is a bonus and obviously helps for the future. It enables you to do certain things in your life that you wouldn’t be able to do without it. But my primary reason for competing is still just the love of it. I truly would be doing this for free, if that were the way it had to be. Luckily, I’m now in a position where I can get paid for doing something I love.”

In the space of four years, St Pierre went from being on top of the world to being a retired former champion. He never lost a fight during that period. He never lost his title. But he lost something.

The wins and dollars kept on coming, though, and after beating Alves in 2009, St Pierre slipped into a trance, defeating Dan Hardy, Josh Koscheck, Jake Shields, Carlos Condit, Nick Diaz and Johny Hendricks, all over the full five-round distance.

Those names, when listed, highlight not only the strength of St Pierre’s stranglehold, but also the elite level at which he had campaigned for so long. Furthermore, it shines a bright light on the grueling manner in which he had to win the majority of his fights, as quick-fire knockouts or submissions proved few and far between.

More often than not, he’d go the full 25 minutes and, at the time of his retirement, St Pierre had spent a whopping five hours, 28 minutes and 12 seconds inside the UFC Octagon. A record. Only a few fighters are even in that ballpark.

His paymasters certainly got their money’s worth out of the franchise known as GSP. That much is beyond dispute. Yet the nagging frustration of seeing a dominant champion dump his title and exit the sport when seemingly at their peak fails to subside. It is also a decision wrapped in confusion and rumor, and so becomes all the more tough to understand and accept.

Most retirement cases see a weathered slab of meat dragged from the ring or cage kicking and screaming, their limbs carried either by sobbing family members or exasperated trainers. Rarely does the story end well and rarely does a fighter call it quits on their own terms.

Defeats were the trigger for legends Chuck Liddell, Matt Hughes, Randy Couture, and Mark Coleman, all of whom retired in their late 30s or 40s having suffered a run of setbacks. Results reflected their deterioration.

St Pierre had no such concerns, of course. He was just 32 when he decided to call it a day – whether permanently or temporarily – and was considered the greatest athlete in the sport, a fitness fanatic, a body beautiful, a competitor who lived for training. Therefore, the idea of sudden regression is laughable.

And even though he struggled desperately in his final defense against Hendricks, the struggle owed as much to Hendricks’ fine wrestling and punch power as it did any sub-par showing on the champion’s part.

No, chances are, St Pierre’s decision to take a break had nothing to do with his physical well-being. If we know anything about the former champion by now it’s that he’s a deep thinker, someone who not only meticulously breaks down fight plans, but also uses this same process to analyze and scrutinize every aspect of his adult life.

Brian McCready, a peak performance coach who has worked on the minds of professional mixed martial artists Andy Ogle and Terry Etim, both UFC Octagon regulars, has watched St Pierre with interest, and he believes it’s simply a matter of motivation.

“He might have Manchester United syndrome,” says McCready, remarking on the demise of the current English soccer champions’ lack of success this season after winning 13 titles in the past 21 years, “where it simply gets a bit boring at the top. Being a Liverpool supporter, I grew accustomed to them winning just about everything as a kid and, in the end, I’d notice that after winning the title they’d basically just walk around the pitch once, pass the trophy about, and then head back down the tunnel. But if Liverpool were to win it now there’d be street parties.

“When you’re expected to win time and time again, it almost feels like something is being taken away from you each time you fulfill expectations. There’s not as much joy in victory anymore. There’s almost an assumption that GSP will win every fight, and beat every contender, so when he does do this, where’s the element of surprise and awe? You get no credit if you’re only doing what people expect of you.

“Every human being wants to be loved and acknowledged, and if you’re no longer getting that, but still putting in the same amount of training, it can be tough mentally. Maybe he wants to go away and reinvent himself and only then will we realize and appreciate just how great he was.”

For years it seemed St Pierre had created his own nest within the welterweight division, such was his degree of dominance. There was him, and then the rest. But now, following five give-and-take rounds spent in the company of Hendricks, there is the sense that there could be parity, there could be competition.

And it’s this realization that makes his exit from the sport such a blow to so many. Nevertheless, McCready fully expects a return in the future.

“History tells us it’s difficult for a fighter to quit at the top because when they’re winning, it becomes addictive,” he states. “They’re releasing all these natural feel-good drugs in the brain – serotonin and dopamine – and that’s addictive in itself. Once they stop competing, these fighters don’t know where else to go to find those feel-good drugs.

“They also miss the adulation; they miss walking out in front of thousands of fans, not as a team, but on their own. All that attention just for them. And St Pierre is human, he’ll miss it. He’ll want more. He’ll want it again.”

It is for perhaps this reason that so many fighters forget to stop, or are simply unable to. Fighters who, though still able, will never scale the heights of old. Fighters like BJ Penn, who insists he has no interest in another world title, and Wanderlei Silva, Dan Henderson, Quinton ‘Rampage’ Jackson and Rich Franklin and the Nogueiras, all of whom will continue to plough away in 2014.

Even Anderson Silva, the greatest of them all, hinted at a comeback just days after snapping his leg in a second loss to Chris Weidman, a man nine years his junior. He, more than anyone else, has grounds to walk off into the sunset, having lassoed the entire middleweight division for seven years and held the record for most consecutive title defenses in UFC history. But, still, he seemingly wants to fight on.

“The Brazilians have this firm belief in religion and they believe they’ve been chosen to do what they do. That makes them all very powerful mentally,” offers McCready. “It doesn’t matter who chose you, if you have faith in a higher power and you believe you have been put on this earth to do a certain thing, that can only be seen as positive. Brazilian fighters have an in-built belief that they are the greatest in the sport and that fighting is their life. This is what they were born to do.”

Joe ‘Daddy’ Stevenson might not be Brazilian but he was certainly born to fight. The winner of season two of The Ultimate Fighter turned professional aged just 16 and now boasts 46 fights to his name. He knows St Pierre on a personal level and applauds the French-Canadian’s decision to call time on his career.

“It’s not surprising at all. He’s been fighting for quite some time now and has been on top of the mountain for years. What better time to step down?” Stevenson says.

“People forget that us guys have lives outside of fighting. We don’t have stories made up for us. Some of us do have troubles and do have to fight through stuff in our regular life, too. Eventually that all builds up.

“You can only keep fighting through all that stuff for so long. Most of us don’t know when to say, ‘All right, guys, it’s someone else’s time.’ Most of us will get dethroned. We will only stop when we can no longer go on.”

Rather than frustrated or disappointed, when Stevenson thinks of St Pierre he smiles.

“People are upset because they didn’t get the ending they wanted,” he adds. “It’s up in the air and the decision has come following a controversial fight. To them, it’s like a movie being turned off with 10 minutes to go. But, as far as I’m concerned, Georges has done a great job. If he stays away, I wouldn’t begrudge him; he’s achieved everything anyone could hope to achieve. And, if he comes back, after he’s fixed his problems, we’ll all pay to watch him fight again.”

With five straight defeats on his own record, the worst run of his career, Stevenson wishes he had St Pierre’s current conundrum. He wishes he had the option to vacate a championship belt and leave a trail of curious looks and suspense behind him. But ‘Joe Daddy,’ a one-time UFC lightweight title challenger, saw his career go down a different path, and now, like so many others, he prepares to go again.

“I’ve quit drinking and changed a few other things in my life,” he admits. “And now I’ve got that sorted, I have to go to the doctor and make sure my body is at 100%. Once that’s done, I’ll be good to go. I mean, I’m still only 31. Yes, I’m sore and a little banged up, but if I do everything right this time, I’ve got a good shot. I achieved everything I did in the past while drinking very heavily, and now I’m not drinking at all.

“Also, I coach a lot of fighters at the gym and seeing them train and compete makes me want to fight again. This sport’s made me love her again. She’ll cheat on you, she’ll make you feel like crap, but you always remember the good times and you always come back.”

Lest we forget, Stevenson had a retirement party of his own in 2004. Back then he decided enough was enough and moved to Vegas to work on getting his jiu-jitsu black belt. And it was only the emergence of TUF that dragged him back to the very thing he left behind.

“That show was easy for me because I no longer really cared,” he says. “There was no pressure, I was just having fun.”

He believes the same theory applies this time round, too. Instead of ring rust, a mini-retirement promises to refresh. “I’ve done pretty much everything I could ever want to do in a fight,” he adds. “So my dream now is to get a title, defend the title and then step back the way Georges has done. I think that’s every fighter’s dream.”

This desire to get out on top extends beyond just mixed martial artists; when the likes of Stevenson categorize themselves as fighters, he opens his arms to a whole host of scrappers trying to wage their own battle with Father Time.

Boxer David Haye, for example, a former world cruiserweight and heavyweight champion, has received as much attention for his retirements and comebacks as his title wins. Even he has struggled to let the credits roll.

“It doesn’t feel like it’s a complete story unless a fighter rises to the top and then falls down again before retiring,” says the 33-year-old. “That’s why people can’t get their heads around a guy retiring while he’s winning and still young and able. It was always my plan to do what GSP looks like he’s doing. I wanted to turn pro, achieve as much as possible in a short space of time, and get out with my faculties intact. My original plan was to get that done before my 31st birthday.”

At first, Haye seemed on course. He won his world cruiser-weight and heavyweight titles before turning 30 and made plenty of cash in the process. And despite losing to Wladimir Klitschko in a heavyweight unification fight in 2011, he remained stubborn enough to stick to his promise of retiring on his 31st birthday.

But, 12 months after losing his belt, he was back in the ring knocking out Dereck Chisora in front of 35,000 fans in East London. “I only took that fight because of the rivalry,” he says. “It was a grudge match for the fans, and I’m glad I took it; it allowed me to put on a show and produce a KO.”

A fight for the fans was one thing, but, midway through 2013, Haye was lining up more fights as part of a second comeback. “It wasn’t so much a change of heart, more a realization that there were still things I wanted to achieve in the sport,” he adds.

“I was in my early 30’s, in my athletic peak, and was still considered one of the best heavyweights in the world. There were big fights out there for me. Big opportunities. If you pass that up, when still able to do it, you’ll only live to regret it.”

As for GSP’s fighting future, only time will tell. But, he did go the distance in his last seven fights. Patient and cautious, he won’t be rushed.

...