Issue 076

June 2011

The 2000 Pride Grand Prix not only introduced us to the ‘Godfather of Ground ‘n’ Pound’ Mark Coleman it also changed the face of the sport forever

The 40,000 people in the Tokyo Dome erupt. Mark Coleman, leaps around fueled by the adrenaline rush of victory. He goes to join the adoring fans, but misjudges his vault over the ropes and is catapulted back into the ring landing on his ass. This moment of comedy and triumph was the climax of the Pride Grand Prix 2000 – the event that changed the face of MMA.

The UFC had consigned the tournament format to the trash can, but Pride revived it with a vengeance – paving the way for multiple future grand prix. The best 16 fighters that money could buy battled it out for the $200,000 prize and the title of toughest man in the world. After a preliminary round in January, the eight still standing assembled on Monday May 1st for the finals.

One name stood out, Royce Gracie, whose clan had dominated MMA. The Ultimate Fighting Championship had been set up by brother Rorian to showcase the family art and Royce swept by each unsuspecting challenger. The Gracies remained unbeaten in the sport, with Rickson starring in the early Pride shows and the Vale Tudo Japan competitions that preceded them. The Gracies were keen to hang onto their reputation. As well as a juicy fee, the Gracies demanded rules that favored Royce’s patient guard game. So, with no time limit in place, he faced Kazushi Sakuraba. Sakuraba was a student of Wigan catch wrestler Billy Robinson with a love of showmanship, masks and capes that he acquired in the crazy world of Japanese pro wrestling. Only 90 minutes later, he was a national hero. The grueling marathon ended when Royce’s corner threw in the towel to save their exhausted man. The invincibility of jiu-jitsu was exposed as a myth. The Gracies were human. More importantly for the development of Pride, they were brought down to earth by a Japanese fighter. The fans had witnessed that homegrown fighters could beat the best and were hungry for more.

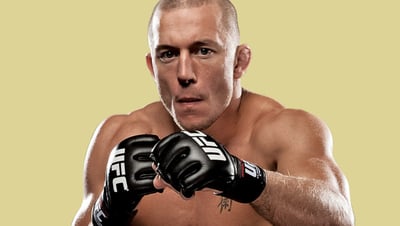

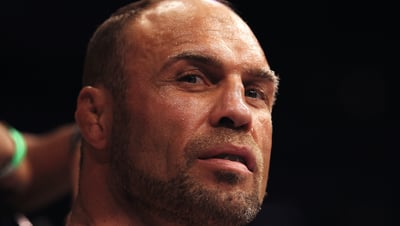

Even before the demise of Royce, Mark Kerr had been the favorite – a fact that attracted unprecedented American interest in a Japanese show. At the vanguard of the new breed of dominant wrestlers, Kerr was being shadowed by a documentary crew. The result, Smashing Machine, is an exceptional film but, rather than following his march to glory, it charts the struggles of a man brought down by drugs and personal demons. He fell to a judges’ decision after a brutal war of attrition against Kazuyuki Fujita. However, along for the ride was Kerr’s buddy Mark Coleman. The 35-year-old had been to the Olympics as a wrestler and had gone on to become the first UFC heavyweight champion but, after a string of losses, he was considered over the hill. (Amazingly, he would take part in a UFC main event against Randy Couture a decade later.)

His incredible underdog story captured the imagination. He defeated Akira Shoji by decision in the quarter final and was due to meet Fujita in the semi. Fujita had taken some hellish punishment in his bout against Mark Kerr and was ready to pull out. In a moment straight out of Rocky, Smashing Machine catches a backstage exchange between Coleman and Kerr. The battered Kerr sees his friend waiting in the wings and says: “He’s not coming next round. It’s yours to win Cole.” The pair then embrace and Kerr buries his head into Coleman’s shoulder.

Fujita did come out, but quit after two seconds – enough time to earn his appearance fee. The refreshed Coleman’s opponent in the final was Igor Vovchanchyn, a Ukrainian kickboxer who was on an incredible 32-fight winning streak. The fight was symbolic of the state of MMA. Coleman took Igor to the ground and kept him there for the 20 minutes of the first round. During, that time, he attempted various submissions with Vovchanchyn simply defending against them. Jiu-jitsu was still a vital, but it no longer guaranteed victory. Everyone was becoming well rounded, but it was the man with the best wrestling who dictated where the fight took place. Coleman – the ‘Godfather of Ground ‘n’ Pound’ – dragged the stand-up fighter into his world and beat him up.

The finish was pure Pride. When reminiscing about the glory days people often talk about the lavish entrances and high production values that were well beyond the pocket of the pre-Zuffa UFC, but they forget about the brutality. In the States, the outlawed sport was being driven towards respectability in order to survive. The very same year, the New Jersey State Athletic Commission drafted the Unified Rules, calling time on the excesses of the early modern era. But there were no such political pressures in the Land of the Rising Sun. With his wrestling shoes giving him a solid foundation, Coleman held his man down and delivered repeated knee strikes to the skull until the submission. The kind of action that made Japan the hardcore fan’s destination of choice for years.

Pride burned bright but was overtaken and eventually shut down by the UFC. 2000 was the last great open-weight competition, but the extended grand prix format became a staple of Pride and lives on today in the form of the Strikeforce heavyweight tournament. The Pride 2000 Grand Prix was the original and the best – a true landmark in the development of modern MMA.