Issue 073

March 2011

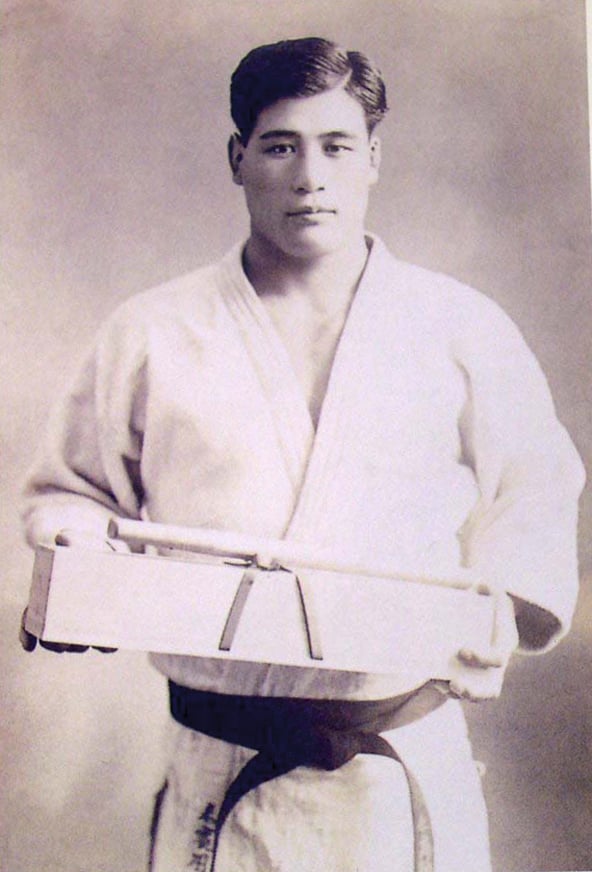

The legendary judoka and inventor of the prolific ‘kimura’ submission hold

Look at every modern mixed martial artist’s arsenal and you will find an essential understanding of how to utilize the deadly ‘kimura’ submission. While MMA fans eulogize one of the most famous submissions in the world, few speak of Masahiko Kimura, the Japanese fighting legend and eponymous forefather who inspired the submission lock that has been exercised throughout generations of warriors.

Boasting a fight career spanning over 25 years, Kimura has watched a multitude of venerable veterans fall at his feet. Most noted is his epic display of bravura against Helio Gracie, father of UFC 1 champion and Brazilian jiu-jitsu pioneer Royce Gracie.

Born in Kumamoto, south Japan in 1917, Kimura started training judo at ten years of age. He went on to become the youngest fifth-dan black belt in Japan at 18. In 1935, Kimura won the All Japan Collegiate Judo Championships. After graduating to the All Japan Judo Open Tournament in 1937, Kimura elevated himself among the elite by defeating the two-time champion Masayuki Nakajima.

It was at this point that Kimura would provide a base for his legacy by becoming the All Japan champion in 1938 and 1939 (and, incredibly, ten years later in 1949). He went on to win a number of other high-profile tournaments such as the Tenran Shiai in 1940, and the West Japan Judo Championship in 1947. Losing only four times in his career, his record alone would be enough to cement him within the chronicles of mixed martial arts history. But Kimura had yet to engage in the battle that would ultimately provide the epitaph of his illustrious fight career.

Come 1951, Sao Paulo Shinbun, a Japanese-language newspaper serving Brazil’s thriving immigrant community, offered Kimura a contract fighting in exhibition matches it sponsored, for generous pay. He ventured to Brazil accompanied by two other Japanese fighters: Toshio Yamaguchi and Kato. Kimura, Kato and Yamaguchi would fight in professional wrestling bouts against local fighters inside colossal arenas packed out with hungry spectators. By this point, Brazilian jiu-jitsu pioneer Helio Gracie could not ignore the publicity the three Japanese fighters were achieving. To him it became a turf war at a time when nations collided over who could prevail as the martial arts supremo. Gracie challenged the visiting Japanese judo experts, and would set the rules for battle: a real fight, to win by submission only. Gracie proved a dominant adversary for Kato, choking him unconscious. The public felt that Kimura and his team had been exposed by Helio. The clash became a matter of pride for the Japanese. The Brazilian then challenged Yamaguchi, but in a spate of indignation, Kimura stepped in to take his place and to exact revenge.

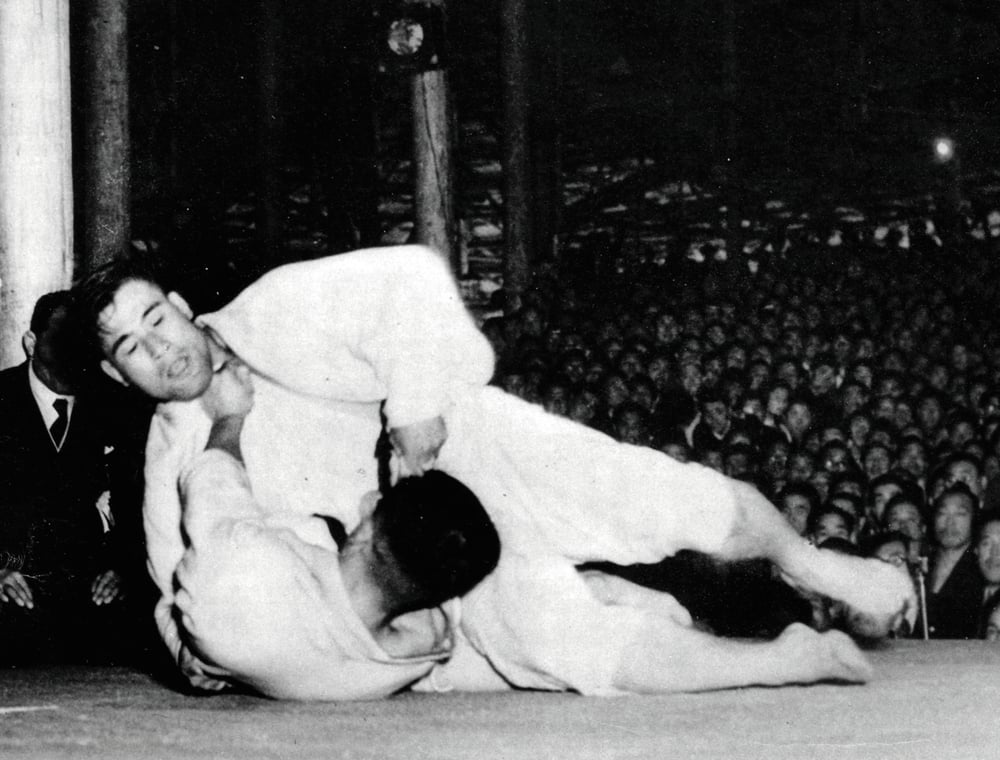

The stage was set. As rolls of newspaper copy hyping up the fight flew off newspaper stands, Kimura vs Gracie attracted the attention of the president of Brazil, who formed part of the 20,000-strong crowd. Gracie later admitted he knew he had no chance of winning: “I myself thought that nobody in the world could defeat Kimura,” he said in an interview in 1994. “Fear was surpassed by desire to know what on earth such a strong man like Kimura would do in the fight.” Gracie found out the hard way. Kimura tossed Helio around like a rag doll right from start to finish. The heavier and stronger Japanese fighter repeatedly threw and pinned Gracie. Kimura choked Gracie unconscious. “If Kimura had continued to choke me, I would have died for sure,” said Gracie. “But since I didn’t give up, Kimura let go of the choke and went into the next technique.” The Japanese then applied ‘Udegarami’ – the shoulder lock that would eventually become synonymous with the fighting elite of the 21st century, tagged by millions of MMA fans worldwide as ‘the kimura’.

Kimura recalled the spectacle in his autobiography, My Judo. He wrote: “I thought he would surrender immediately. But Helio would not tap the mat. I had no choice but to keep twisting the arm. The stadium became quiet. Finally, the sound of bone breaking echoed throughout the stadium. Helio still did not surrender. His left arm was powerless. Under this rule, I had no choice but to twist the arm again. Another bone was broken. Helio still did not tap. When I tried to twist the arm once more, a white towel was thrown in.” Kimura became permanently linked with the development of jiu-jitsu and vale tudo, the influential forebears of modern MMA in Brazil.

Kimura went on to travel the world, competing in exhibition wrestling bouts and teaching judo. Between 1955 and 1958 alone, he resided in Mexico, France, England and Spain. He was called back to Brazil in 1959 for one final vale tudo match, this time against Waldemar Santana – who had previously defeated Helio Gracie. Santana was 27, an expert in jiu-jitsu and boxing, and was a beast at 92kg. Kimura was 42 and weighed around 80kg. With both fighters bruised and bloody after 40 minutes, the match was declared a draw. The fight would be Kimura’s swan song. He passed away from lung cancer in 1993 aged 75, yet every time the screams of fans resonate around the Octagon as a fighter’s shoulder is cranked to near breaking point, his name well and truly lives on.

...