Issue 061

April 2010

The sport of mixed martial arts is in a turbulent patch. Fans of the game are vociferous that the current judging system is ill-equipped for today’s fights. Their fuel is a string of high-profile matches gone to the wire, though apparently leaving the ‘true’ winner with a loss.

With all this controversy, people are beginning to demand a change to the judging system. Can it be bettered? Are judges truly qualified across all facets of MMA? Worse still, is it eroding the credibility of the sport?

Whenever a controversial decision occurs, two factors are blamed: the judges and the scoring system. Presently, mixed martial arts bouts are judged on the ten point-must system. It is a set of criteria decided upon in 2000 and specified in the ‘Unified Rules’, essentially today’s MMA rulebook. It’s a system borrowed from boxing that, applied to MMA, asks judges to score fights based on effective striking, effective grappling, control of the fighting area, effective aggressiveness and defense.

A fighter is awarded a 10-9 round when they get the better of the criteria by a substantial margin, or a 10-8 where a fighter overwhelmingly dominates. Rare (but possible) is a 10-7 round, though one fighter would have to totally dominate their opponent, and it is more likely a fight would be stopped than allowed to continue. A round can be called a draw (a 10-10 round) when both contestants fight evenly with no one showing clear dominance. If all rounds are completed, the three judges’ scorecards are taken into account. The points each judge has awarded are tallied up separately, resulting in a winner on each judge’s scorecard. The fighter named as the winner on the majority of cards is declared the victor.

That seems straightforward, and in fact the full Unified Rules give further guidance, stating that if the majority of the round is spent standing, effective striking should be considered more than any grappling exchanges, but if the fighters were predominantly on the ground, effective grappling should be accounted for first. As America is the host of the world’s premier MMA organization, it stands to reason that rules and practices (as decided upon by the country’s various athletic commissions) tend to become the norm for all of Western MMA. This makes the Unified Rules the focus point for the MMA world.

The oft-cited problem with the ten point-must system is that the guidelines are too ambiguous, but this close inspection of the scoring suggests otherwise. If the rules are specific and clear, is there really any problem with the scoring system? “I think the ten point-must system is still the best one out there that I’ve seen,” states Keith Kizer, executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, the body that regulates MMA in Nevada, the home of all Las Vegas fight cards. In fact, Kizer, along with other influential members of the MMA community, looked at alternative judging options and submitted a report to the Association of Boxing Commissions as recently as the summer of 2009.

“We looked at different types of scoring systems and nothing was better than this. We understand that this is not perfect,” concedes Kizer. “Are there issues? Yes, there are issues. Do I still think it’s the best system out there for scoring mixed martial arts? Yes.”

That won’t satisfy many of the fans who are convinced change is necessary. But if one thing irks them more than scoring, it’s those who apply it.

There has been great speculation over the competency of judges; with so many unpopular decisions it’s hardly unsurprising. But the majority of judges are not as green as many people imagine. Nick Lembo, legal counsel for the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, one of NSAC’s opposite numbers, explains the stringent process by which someone becomes an MMA judge. “You have to have some background in jiu-jitsu, wrestling, judo and / or Muay Thai. Then you have to attend a seminar. At the end of that seminar you have to score rounds of past fights that I have selected on DVD. You start as a shadow inspector in our amateur program. Then you work your way up to a chance at being a shadow judge. As a shadow judge, you score as the fourth judge at amateur shows. Your scores are collected but they don’t count. Then, if your scores are good after shadowing for a while, you will get a shot as an actual amateur judge. From there you score bouts for years and may work your way into the pro ranks.”

With a very similar process in Nevada, what kind of specific training are judges given, if any? Keith Kizer confirms, “We do have some mandatory training, but there’s a lot of optional training.” Indeed, legendary referee ‘Big’ John McCarthy runs his own training program for referees and judges, and Nelson ‘Doc’ Hamilton does the same. The latter has even produced DVDs on the subject.

Despite all the required experience, shadow judging and seminars, some officials still produce scores that are skewed in an unexpected direction. Being ringside for countless important MMA and boxing matches, Keith Kizer knows more about a judge’s perspective than many. He suggests that a judge’s position around the ring might be a very influential factor. “On the Tito / Forrest fight, I thought Tito won the first two rounds. I don’t think it’s a coincidence it turned out that the judge I was sitting next to is the one that had Tito winning the fight 29-28. I had the exact same scorecard. But, I wasn’t on the other side of the ring, where I know almost everybody in the press gave the first round to Forrest, as did one of the judges that was sitting right in front of the press row.”

So perhaps the ten point-must system is fair; judges are trained and the majority of skewed scorecards can be explained by mere perspective. Maybe these controversies are simply the nature of subjective judgment. But, is there not a way to just add to the current system without abolishing it?

Frequently raised by revisionists is the concept of awarding points for particular moves, with a fighter awarded points for a submission attempt, takedown, successful strike and so forth. The obvious extension of this would be using real-time fight statistics created by companies such as FightMetric and CompuStrike, which track the number of offensive and defensive actions. But even these purely objective sources are limited. “They don’t always tell the exact story,” says Marc Ratner, vice president of regulatory affairs at the UFC, a hugely experienced and respected figure in the fight world. “Who’s doing the most damage? Who’s imposing their will on the other fighter? I would be against them using any electronic means because you’ve got to judge it.”

Keith Kizer agrees: “A submission where you get a guy in an armbar that he slips out of after 20 seconds without much trouble, should not be scored the same as a guy that’s in an armbar, who, during those 20 seconds, was in some pain, or there’s residual pain when he gets out.” Furthermore, it’s a real possibility that if fighters know their number of strikes will be a deciding factor, they’ll simply fire off as many punches and kicks as their cardio will allow. While it could make for short, exciting exchanges, it’s far more likely to result in sloppy fights where competitors are gassed within a few minutes – not what fans want to see and not what MMA is about.

Also suggested, is taking the whole of a fight into account when scoring, much like the Japanese method (emphasis is particularly given to the fighter who finishes strongest, and tries to end the fight rather than ‘ride out’ a decision). But that’s liable for a skewing of its own, as the final minutes often carry a disproportionate amount of influence and can lead to an arguable decision.

Alternatively, a half-point scoring system looks to abolish the trouble of distinguishing between 10-10, 10-9 and 10-8 rounds by adding a half-point in between. For example, an extremely close round could be scored 10-9.5 if a fighter marginally outscored their opponent in one of the criteria. A 10-9 would now be won by a clear advantage, a 10-8.5 by dominant advantage or a 10-8 by overwhelming advantage. Out of all choices, this seems like the most sensible and even option, provided judges fully embrace the scoring definitions.

If change were to come, how would it happen? Many fans are applying pressure to the UFC directly, but can the UFC even influence the rules? “No, because we’re a promoter first,” states Marc Ratner. “What there would have to be is for the State of New Jersey or the State of Nevada, or whatever, to be at the Association of Boxing Commissions – they would all have to get together at their annual convention and make a decision to change the way they score.” After that, the separate states would then have to adjust their guidelines, dependent on their government processes. These are quite lengthy unless they are what’s called regulatory changes.

In fact, Nevada passed a regulatory change at the end of October 2009, regarding instant replay. It can only be used for fight-ending injuries, to clarify if a blow that caused the halt of a contest was legal or illegal. For example, if a cut ended a fight and it was unclear whether it was an elbow or a headbutt, officials could determine if the bout should be ruled a TKO, disqualification or no contest. It’s at least some consolation to restless fans that improvement is ongoing, and the various commissions are sensitive to necessary changes.

There’s growing concern that after its long struggle to quasi-social acceptance, these controversial decisions are harming the credibility of MMA. “Controversy by itself doesn’t harm it if there’s a lot of people on both sides arguing the point. That only shows that it was a well-matched fight,” argues Kizer. “I think what does hurt the credibility is bad decisions. But the decisions that have been criticized, at least lately, I see a lot of people on both sides arguing the case.” Marc Ratner also thinks that provided both corners have an argument for the win, it doesn’t remove from the credibility of MMA.

“The controversies, they’re going to be part of the sport, they’re not going to be perfect. But it also leads to interest in another match, even though it’s in a negative way, but rematches sometimes come from close fights that have a little controversy in them.” Is the UFC concerned that the recent spate of arguable decisions will turn off fans? “No, I think they get aggravated, but we’re having 11 fights on a card, and it so happens that in the last couple fights there were controversies in the main event. But, if you look back over the last couple years, there have been a handful of controversies, but I don’t think it’s been a trend.”

Maybe that’s the real argument to take note of. Although there were three high-profile, debatable decisions in the latter portion of 2009 (namely Shogun-Machida, Griffin-Ortiz and Couture-Vera), there have been few in proportion to the huge number of fights the UFC and other organizations hold. Only a small number of the fights that go to decision are ever seen as controversial.

Maybe the answer is within the ten point-must system as it stands. The ability to score rounds more openly is there, reminds Marc Ratner. “I think there has to be a little more liberalization, and what the judges have to do is have a little more commonality of philosophy, and give more 10-8 rounds.”

If we accept that the current system is partially flawed but accurate overall, then who is to blame for the troubled decisions? Is it the commissions for not accurately communicating the scoring criteria to their judges, or the promoters’ fault for not properly informing their fans? New Jersey’s Nick Lembo comments, “Our judges are fully expected to be well versed in the scoring criteria. I think some fans take what the commentator is saying and take his or her word as gospel. I also think that fans need to score fights with the sound off, without socializing, and devote their entire attention to the bout.”

Marc Ratner suggests that there could be elements of both, but something else could be at play. “This is still a very brand new sport, and we just have to remind people that it’s evolving. The sport is changing. At one time, the fighters were strictly striking. Then it was more jiu-jitsu, and then it was a combination of everything – the judges have to adjust.” That’s a great point. MMA has only been around since 1993 and is still growing. It’s only in recent times that fighters have become true mixed martial artists, so the idea that judges too will improve, and become specialized in mixed martial arts, is important to remember. “What will eventually happen, I believe, is a lot more former fighters will get into judging and refereeing. Right now, that generation is getting ready to get more into the sport and give back.”

When the whole picture is taken into account, it’s evident that possibly only minor changes or clarifications need be made. Most judges are competent, but have to contend with bad angles and the fact that all subjective judgments are debatable, but they will undoubtedly improve as the sport continues to develop. The scoring itself is deep, and the ability to score fights in a more flexible manner is present. It just has to be embraced. Perhaps a small alteration such as the half-point system could help, but some state regulators aren’t fully convinced just yet.

Maybe the slow progress is for good reason. If a change were to happen, it has to be right first time. Hasty patch-ups will not bear the weight the ten point-must system has supported so far.

FOUR OF THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL DECISIONS EVER

Bas Rutten vs Kevin Randleman, UFC 20

Held prior to the application of the Unified Rules, Randleman repeatedly took down and dealt significant damage to Rutten from inside his guard for the vast majority of the 21-minute heavyweight title fight. Rutten kept Randleman from advancing his position and continually struck back from the bottom.

Winner: Rutten by split decision

Wanderlei Silva vs Mark Hunt, Pride FC: Shockwave, 2004

Even Mark Hunt looked surprised by the score announcement, but he rocked Silva multiple times, escaped submission attempts and scored plenty of damage while inside the guard. Silva took the fight down at will and recovered quickly – this contest is possibly an argument against scoring a fight as a whole.

Winner: Mark Hunt by split decision

Michael Bisping vs Matt Hamill, UFC 75

This was a very close fight; Hamill landed multiple heavy shots and scored a number of takedowns, but made little progress on top and rarely kept Bisping down for long. When ‘The Count’ did gain his footing he made Hamill pay, peppering him with crisp strikes.

Winner: Bisping by split decision

Lyoto Machida vs ‘Shogun’ Rua, UFC 104

In a bout where ‘The Dragon’ was punished with leg kicks, and it seemed his evasive style had been cracked, many thought ‘Shogun’ would be the new champion. Machida’s strong exchanges and his control of the engagements meant the judges saw things differently.

Winner: Machida by split decision

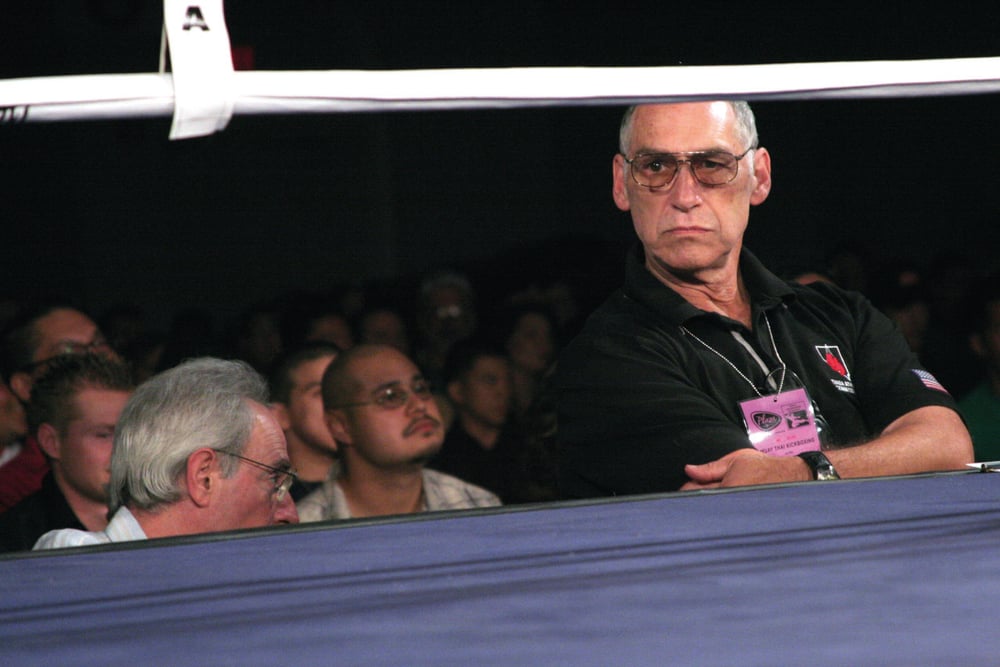

A JUDGES' PERSPECTIVE

Nelson ‘Doc’ Hamilton is a highly experienced referee and judge with over 30 years of martial arts experience. There’s no one better to talk judging with than him.

How hard is it to judge a fight?

It depends on the fight. Those fights that are called controversies, there’s at least one round that is extremely close insofar as the action goes. It somewhat follows the pattern where one fighter wins one round and the other fighter wins the other round, and nobody really has anything to say about that, but then it’s that odd round that everybody gets upset about. There’s always going to be a fraction of the viewers that aren’t going to be happy with the decision. It’s not an exact science. Some fights are just easy to see because somebody dominates the striking or whatever.

Are the majority of judges, who you come into contact with, competent?

The majority of judges at the level of UFC or Strikeforce, or something of that nature, are competent. With very few exceptions, I have no argument with most of my colleagues at that level. They know the criteria, they’ve studied what’s going on, they’ve worked lots of fights. I’m not denying the fact that there might be some people that really don’t know the ground game and that influences the score, because if there’s a lot of groundwork, they’re not quite as competent as they are at stand-up.

Do you think the half-point system you have suggested would lead to fewer debated decisions?

I come from the premise that there’s no perfect scoring system, and that being the case there’s always going to be controversy. The only thing you can do is try to make the scoring reflect the action that took place in the ring, so the fighter that deserves the win, does win. Scoring a fight is more than determining who won a round; the score should also reflect the quality of the win in that round. What the half-point system does is, it gives judges a lot of different tools in order to cope with rounds. The half-point system, it’s not brand new – we’ve used it in K-1 and it worked well for us. There are about six or seven judges that are working fights for the UFC, in various cities, that have used it. There is a core of people that are familiar with it, and I would say they all like it. On those rounds that you come away scratching your head, you can say, ‘Well, 10-9.5, that’s not a problem.’ With this system you might have more draws. Nobody likes a draw – so how do you settle a draw? You go ahead and use technical merit. There would be a fourth judge who just scores the match from a standpoint of technical merit. That’s the fairest way, because then we’re doing it on the basis of objective criteria.

For more information on ‘Doc’ Hamilton’s half-point system, visit www.mmarefs.com

...