Issue 039

July 2008

“They need to be taught the mindset of how to be successful in a life-or-death situation. It is more important to teach them to be warriors than to teach them any particular skillset.”

The images of warfare on our TV screens often resemble a high-tech video game, with missiles accurate to the millimeter and souped-up tanks that demolish anything in their path. The reality is somewhat different. Areas need to be secured street by street, house by house. Close contact with hostile forces is common, so it is vital that a modern soldier has the ability to deal with such situations. As firearms expert Massad Ayoob put it, “At close range it’s not a shooting contest; it’s a fight.”

The world’s most powerful fighting force, the United States Army, addressed this issue by implementing the Modern Army Combatives Program (MACP). Modern Army Combatives grew from the same roots as MMA and shares many common features with the sport.

1995 was the US Army’s Year Zero. The Commander of the 2nd Ranger Battalion decided that hand-to-hand combat needed a revamp. It quickly became apparent that the old field handbook and training methodologies were not fit for purpose. A committee was formed to overhaul close combat training. Staff Sergeant Matt Larsen had a background in judo, boxing and Muay Thai, and was the most experienced fighter involved. He soon became the driving force behind the project.

The early Ultimate Fighting Championships were set up as a clash of fighting styles to see which was the most effective. Although the committee formed not long after the original UFC, Larsen insists that the timing was purely coincidental. The Army conducted its own trials.

A class of 100 infantrymen, wanting to join the Rangers, were split into two groups. During their induction, one group had ten hours of boxing instruction while the others had additional physical training instead. At the end, the two groups boxed. The non-boxers won more fights. Even when the training time was doubled and professional coaches came in, the result was the same. When the experiment is repeated with ground grappling the trained grapplers win almost 100% of the time.

Theories of fighting were being rewritten. Matt Larsen would often refer to Royce Gracie’s dominance of the early UFCs when explaining his findings to the Army’s top brass. He is adamant that there can be no turning back:

“The concept of individual martial arts styles is archaic. It’s just somebody’s opinion of how you should train. None of the legacy arts have the answer. Yet the answer isn’t to cross-train. That leaves you with disconnected technique. You need integrated, realistic training. Ground grappling, stand-up, takedowns, clinch fighting, etc. That has evolved out of MMA and we are spreading those principles of realistic training and putting them in the context of the battlefield.”

Matt Larsen is now the Commandant of the US Army Combatives School, (USACS) which he founded at Fort Benning, Georgia. The success of his work with the Rangers spread and developed into the Modern Army Combatives Program. The US Army Field Manual for Combatives (FM 3-25.150) demonstrates the core techniques that have been found to be most effective. In the early days, Royce and Rorian Gracie made a number of visits to the 2nd Ranger Battalion to share their expertise, and the weapons section had plenty of input from Marc ‘Crafty Dog’ Denny of the Dog Brothers, the leading light of Real Contact Stick Fighting.

If you read the manual (it’s freely available online), you will see what looks like a guide to modern MMA. There are no Vulcan death touches, just a collection of straightforward jiu-jitsu and striking techniques; handy tools that can be picked up quickly. The revolutionary change signaled by the Modern Army Combatives Program is the focus on teaching someone to think like a fighter.

One of the basic tenets of Modern Combatives is: “The defining characteristic of a warrior is the willingness to close with the enemy. We do not win wars because we are better at hand-to-hand combat than the enemy, we do however win wars because of the things it takes to be a good hand-to-hand fighter.”

As Larsen says of recruits: “They need to be taught the mindset of how to be successful in a life or death situation. It is more important to teach them to be warriors than to teach them any particular skill set.”

The logic is simple. Any opponent, military or civilian, is likely to use what Larsen calls the “universal fight plan”. They will try to pummel you with fist and boot until you are incapable of fighting back. Most martial arts have the same plan, but they teach you skills so you can execute the plan more efficiently. To become a better fighter, you need to develop skill and that takes a long time.

Instead, the army teach the basic, ‘rice and beans’ plan: close the distance, achieve the dominant body position, finish the fight. These concepts can be taught in a matter of hours, along with the idea you can tackle anyone who tries to punch you. Sparring with resistant opponents bolsters the learning and inspires confidence.

The theory is, six months down the line, a soldier will still be a better fighter. Even if he has forgotten all the techniques, he will know the position he needs to get to. Once he has achieved a dominant position he can finish the fight with punches. A takedown will not be the right option in every situation, but the training instills the idea of taking the initiative. The fighter who dictates the range and the angles will usually win the fight.

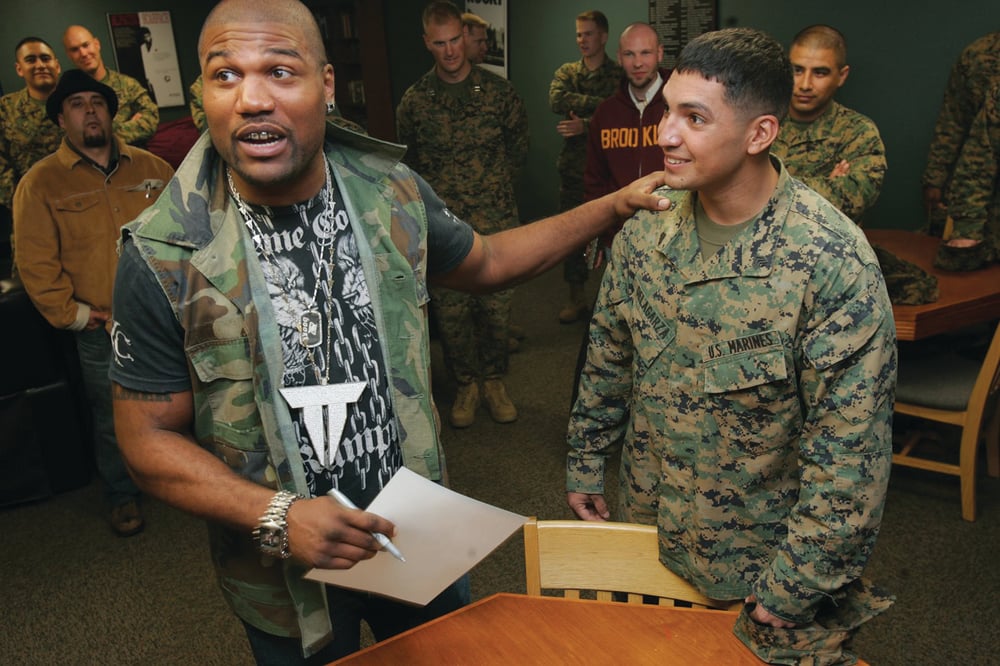

Over the years, plenty of stars, such as Forrest Griffin and Matt Hughes, have been to Fort Benning to lend a hand. Matt Larsen concedes that there are similarities between the sport of MMA and what is happening in the army.

“MMA is evolving. It’s a parallel evolution within our program. In many ways, the lessons of MMA translate directly into what we’re doing. For example: the emphasis on clinch fighting, that’s gone on in the last few years, has become a big part of what we do because we find the same thing happens on the battlefield. In that situation, things like knee strikes and judo techniques are really in their infancy of evolution in MMA and the same things are going on in our program. Of course, it’s slightly different when you’ve got your rifle and grenades hanging off you.”

The previous sentence drives home the fact that we are talking about life and death here. MMA comes close to replicating real fighting - but it is only a sport. Hundreds of post-action interviews have been conducted by the army to assess what works and what doesn’t, with all the information fed into improving the training. There are two huge lessons from hand-to-hand combat in Iraq. First, every fight is a grappling fight. Not pure grappling, but grappling with strikes. There’s got to be a reason why they’re not shooting the guy. That reason is usually that the opponent is too close.

At times like this, it is wise to remember the other basic tenet of modern combatives: ‘The winner of a hand-to-hand fight in combat is the one whose buddy shows up first with a gun.’ There is no need for training against multiple opponents. If bad guy B arrives on the scene before you finish the fight, he’s probably going to shoot you.

The second major lesson from Iraq is that there is no such thing as unarmed fighting. Almost all hand-to-hand fights on the battlefield involve grappling over a weapon. It doesn’t matter who brings a knife or gun to the fight, it’s all about who gets control of it.

Matt Larsen explains how this can be recreated in training: “When a guy is basically a good ground grappler, we introduce weapons. You don’t ever know if a guy’s got a knife. It’s not like West Side Story where I get my knife out and we’re dueling. So I make them all close their eyes, I take a 100,000 volt stun gun and put it in someone’s pocket in the class. I put them to grapple and they don’t know who’s got the stun gun.

“Two things happen. The intensity level goes through the roof because everybody’s scared of the electricity. The second thing is, they learn that it’s all about controlling the guy. If I have a knife in my pocket I have to be able to get it into my hand to use it. If I’m reaching for it, you’re going to know. It’s the guy in control who gets it. Once we’ve established that we can fight over pistols and rifles. Nobody in the MMA world is teaching that. Those are lessons from the battlefield. How we do it has grown out of what we learn from jiu-jitsu and mixed martial arts.”

In the military, the hierarchical command structure means that policy is dictated from the top. The Modern Army Combatives Program came from the grassroots, but was so successful in teaching people to really fight, it swept throughout the US Army. From being virtually ignored, the whole culture of the army has been changed, so that hand-to-hand fighting is valued.

Competition plays a vital role in this new ethos. Each year, approximately a quarter of a million people go through basic training. All of them are now required to fight competitively. Every unit is also required to hold an annual tournament. At battalion and lower level, the fights are grappling matches. The idea is to motivate every member of personnel. In an environment where your life could depend on the person next to you, nobody wants to be labeled a substandard fighter. The competition encourages training, which obviously raises standards. The measure of success is the ever-improving level of the average soldier.

The winners progress to brigade level and fight under the intermediate rules, which include limited striking. Next is the division (10,000 -15,000 men) championship under the advanced rules. The advanced rules are, in essence, MMA. Last year, Fort Knox became the first post to hold an official combatives tournament in a cage instead of a boxing ring.

The pinnacle is the two-day All Army Combatives Championship (AACC). Each division sends two men in each weight class to Fort Benning in a tournament, which mirrors the graduated rules of the earlier rounds. The fighters wear fatigues and grapple, just as all their comrades have previously. The winners progress to the championship round and fight MMA rules. Using graduated rules is a reminder of the purpose of the tournament. It means that a pure striker or grappler will not be successful. A champion needs to be well rounded: an example to other soldiers.

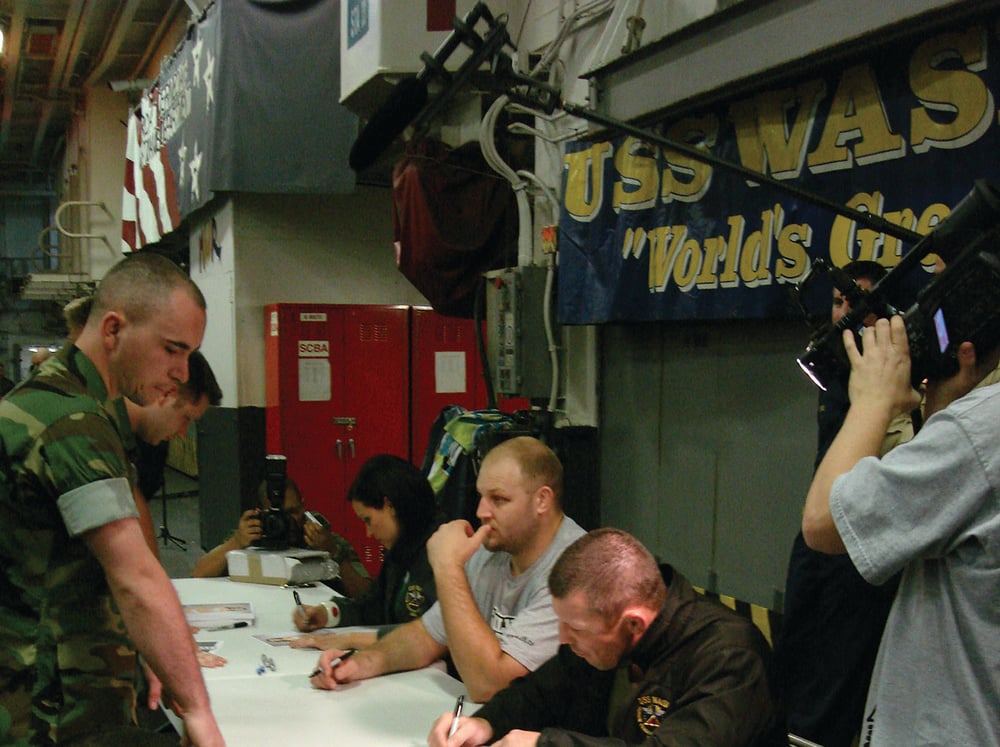

The AACC has been a huge success. The action is packaged into the TV show T.O.P. Army Fighter, which airs on the Military Channel. Around the world, troops follow the tournament via AKO (Army Knowledge Online) and the Army Times. The fights have a raw quality as the soldiers battle it out for the honor of their unit. The AACC is fundamentally a modern mixed martial arts MMA show, without any of the tacky marketing. There are no ring girls or trash-talk exchanges. The event exists to promote excellence in fighting and encourage good practice in the ranks. Sergeant Tim Kennedy is the most successful AACC competitor, winning three consecutive titles.

Iraq veteran Kennedy has gone on to compete successfully in pro-MMA with the International Fight League while still serving. Many MACP instructors also fight on MMA shows with the blessing of their employers. This is seen as professional development in much the same way as army doctors hone their skills in civilian hospitals.

The world’s most powerful entity has embraced the principles underlying mixed martial arts MMA to the extent that they require each of their number to compete. At a time when the sport is still fighting for acceptance, the US Army is a useful ally to have.