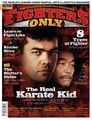

Issue 055

October 2009

Sixteen years ago, Royce Gracie revolutionized the martial arts world by using a Japanese martial art (jiu-jitsu) to beat 11 opponents and win three UFC tournaments. No holds barred developed into MMA, a new sport where all styles were mixed into one. The world thought there were no more techniques to be added to this sport, but another Brazilian using a Japanese martial art (this time, karate) appeared and turned things upside down once again.

At first, some thought his style was boring (just like Royce’s), but as Lyoto Machida worked his way through the toughest UFC fighters, some of them specialists in Muay Thai and boxing, people began to respect him.

If there were any doubts about how efficient Machida’s karate style is, they were destroyed in eight minutes and 57 seconds last May. That was all Machida needed to knock out the undefeated UFC light heavyweight champion Rashad Evans at UFC 98. “I trained with the best teams, with the best trainers and partners around the world, and I found the secret that I was looking for inside my own family: Machida karate,” said Lyoto, a black belt in Shotokan karate.

A day with the Machida Family

There couldn’t be a better way to understand Lyoto and his Machida karate than to spend an entire day with the man this story starts with, Yoshizo Machida. I was lucky to arrive in Belém on a Sunday, the only day of the week Lyoto rests and recharges his batteries, and I spent the whole day with his brothers and wife in Yoshizo Machida’s house, traveling straight there after Lyoto picked me up at the airport. “Sunday at my father’s house is when and where I recharge myself for the next week of training,” explained Lyoto as we drove out to the borough of Ananindeua, 25 minutes from downtown Belém, where he spent most of his childhood. “No matter what happens to Lyoto, he comes. This is something that he cannot live without,” revealed his wife.

Upon arriving at the house, we were received by Dona Ana Claudia (Lyoto’s mother), and met his brothers (who act as his trainers) Take and Chinzo. Yoshizo, the 64-year-old patriarch of the family, met me with a glass of beer and a bowl full of crab meat. From then on, the chat flowed beautifully. Between sips of beer, the gentleman samurai, very much ‘Brazilianized’ by his time in South America, told me of his life history and helped me to better understand the origins of Machida karate.

The saga of a samurai

Passionate about challenges, Yoshizo Machida decided to come to Brazil when he was 21 years old with only three sets of clothes, three words in Portuguese (“hungry”, “good day” and “good afternoon”) and a strong desire to spread Shotokan karate as taught to him by his master Masahiko Tanaka (a three-time world champion). With the help of the huge Japanese community in Pará, Yoshizo spent a year employed in a civil engineering company, but when the contract ended in 1970 the 7th Dan karate master decided to fight in a karate tournament in Brasilia. He won, and received an invitation to open a karate academy in Bahia. There he met Dona Ana Claudia, with whom he married and had four children: Take (34), Chinzo (32), Lyoto (30) and Kenzo (26). Kenzo is the only son who does not live to fight – he is a reporter in Brasilia.

In 1980 (when Lyoto was only 4 months old) Yoshizo decided to return to Belém. He opened his own academy in a two-story house in the city center and it was there that Lyoto and his brothers practiced their first katas. “The first floor was the gym, and we lived on the second,” Chinzo remembers. His father notes that because of the physical similarities between him and his second eldest son, Chinzo was raised in his image and likeness. “Since I am short and have always fought against much larger opponents, I developed my speed so as not to let my opponents overpower me,” said the family head. “While they were still thinking, I was already in there and Chinzo, being physically built much like me, developed this same style. Lyoto, who is larger, has always waited longer to attack, but Lyoto is also increasingly developing his aggressiveness and speed.”

Chinzo was the first of the sons to get a black belt, receiving his at 10 years of age. Lyoto got his at 13, and Take, more concerned with his studies at school, only received his from his father at 17. Until they got their black belts, Chinzo recalls that he and his brothers did not have an easy time in the hands of the Japanese samurai. “My father was always very hard and valued our unity as a family. Once, when Kenzo was about six and Lyoto about 11, they had a big fight, and my dad asked if they liked each other. Lyoto said no and Dad drove them both out of the house. The two slept on the street in front of the academy. In the cold street, the two had to come together and help each other. The next day they came to apologize to my father, already friends again.”

The first challenges

When jiu-jitsu exploded after the UFC in the mid 90’s, the challenges between representatives of jiu-jitsu, karate and kung fu academies had become more frequent in Brazil. Yoshizo had to spread his philosophy throughout Belém. “Sometimes someone would come challenging and my father would say that he would lock the gym and only one would leave alive, then the guy would think twice,” recalls the elder of the Machida brothers.

“In school, everyone spoke only of jiu-jitsu. We would say that Royce´s jiu-jitsu was very good, but that our karate was also good, that there was space for everyone, but it made no difference and some friends who were into jiu-jitsu would always show up to test us.” At the time, Lyoto, who was about 15 and had some experience in judo and jiu-jitsu, was chosen to do the honors of the house. “He wouldn´t let anyone grab him and kicked their asses, so people began to say that our karate was different and we came to be respected in Belém,” recalls Chinzo.

Recovering karate

Training in Los Angeles during his first trip outside Brazil, Lyoto realized that it would not be easy to spread his karate in a world governed by Muay Thai, boxing, wrestling and jiu-jitsu. “I was on a plane and a guy who did not know I was a karate fighter asked me: ‘Are you a fighter? I trained in karate at Tanaka´s in Rio – at that time, we thought that karate could be used for something’.” The statement from a fellow karateka made Lyoto angry. “That hurt me a lot, a guy who trained the same style that I did, saying that everything he trained was lies? With each statement I heard like that, I felt more and more like showing them that it is the case,” recalls Lyoto.

“In the past karate was used for self-defense in real fighting, my teachers and I believe that the true philosophy of karate is to define the fight, in the same way that judo has the ippon and jiu-jitsu the submission. We are trying to bring that mentality back,” says Yoshizo, who explained that he constantly pulls at his son´s ears to make him more aggressive. “I always fight with Lyoto, tell him not to give points to the opponents, but to finish the fight as soon as possible.” Yoshizo recognizes though that Lyoto´s style is very different to his. “Because he has a different style from that of Chinzo, Lyoto has developed his defensive side, which has been very important in MMA – it is not for nothing that Lyoto is the only one who never gets hit,” says Yoshizo happily. Against Rashad, he told his son to change that characteristic: “I told him to score a knockout right at the beginning of the fight, and he did just that.”

For Lyoto to beat Rashad like that, the Machida family worked hard, as older brother Take says. “We studied his every move. We had 18 very well-trained ushikomis. For each attack he had, we had three counter-attacks. We tried to make Lyoto have the shortest possible entry delay. We studied in detail, identifying the moments when the opponent was vulnerable after trying a move, and, in that fraction of a second, Lyoto would enter. If a karate fighter has his entry and timing well adjusted, it is very difficult for the opponent to touch him.”

Brother vs. brother

Yoshizo encouraged the brothers to compete among themselves, and they would sometimes end up fighting each other in competitions. “My father always said that the samurai is alone and taught us to fight for ourselves,” said Lyoto. His brother Chinzo has scar below his eye which he received from Lyoto in the final of a tournament. “Our karate has no weight categories, so I fought against Lyoto in several final matches in championships. My father always loved it,” he said. “On the day he was cut, we all went to the hospital to sew it and celebrated the victory together.” Chinzo would become go on to Brazilian karate champion. “My brother is like a mirror. We think the same way when we fight, so I need him in my corner,” says Lyoto. “When the fight is on, it’s as if we were fighting two against one,” says Chinzo. “I was happier when Lyoto won the belt than when I was vice world champion of karate.”

Lyoto a former Brazilian and Pan-American karate champion, had decided at age 15 when he saw Royce winning the UFC that he wanted to be champion in MMA. “Lyoto wanted to fight his first MMA fight at 17, and my father said it was criminal fighting, but that after he graduated from college, he could do whatever he wanted,” says Chinzo. Because in the Machida family, the strong give orders and the wise obey, Lyoto graduated in Physical Education from the University of Pará before showing the world the effectiveness of his father’s karate.

Despite being very proud of the karate his son has been showing in the UFC, Yoshizo made clear that he was also impressed by two other fighters. “I like Minotauro because, even on the ground, he works out the situation calmly. He is well-programmed. I like Anderson Silva’s fighting because he is a showman. Basically, I think he can knock his opponents down any time he wants to.”

Training like a champion

“Training is one of the important factors for the athlete to achieve his best. Undoubtedly, Belém is the place where I can bring together the positive factors to improve my performance in the ring. That´s why nothing will ever make me leave this town,” says the UFC light heavyweight champion. Lyoto´s results have bolstered the ranks of the Machida family academy, which today has 300 students of karate, 150 of judo and 60 of jiu-jitsu.

After almost nine months of training without a break, Lyoto finally got eight well-deserved vacation days upon winning the belt, enjoyed with his wife Fabíola and his son Tayo in Natal. But to his wife’s surprise, as soon as he got to Natal her husband called a physical trainer and asked for a workout because he was anxious to train. “The moment that the fight is over, training becomes my hobby. I love running, I love putting on the kimono, training lightly, positioning, training with the younger guys – I love it. Consequently, it refines my movements and agility,” he said. He managed to spend eight sunny days in Natal without going to the beach once.

Lyoto recognizes that when the time for the competition approaches, the pleasure of training becomes work. “You have to withstand five rounds, you have to lift 150 kg, all of which is tiring. I want to fight only about five or six more years, depending on how much more my body can endure. Most important is that I love what I do and would not change my life to be a doctor, a lawyer, or anything. Since I was 17 and saw Rickson and Royce in Tatame Magazine, I have studied every detail of the pictures and imagined myself there – just like what is happening today.”

What is amazing is that Machida was getting excellent results without any kind of physical preparation. When he hired a professional trainer, Lyoto’s performance took off. Just compare his performance in the fight with Tito Ortiz to his two most recent wins, both via knockout. Eduardo Bastos Lisboa, a black belt in karate under Machida Senior, has known Lyoto since he was eight. “He has loved to train since he was a child. My biggest problem was convincing him to train less and with more restraint. Lyoto seemed like a caged jungle cat,” says Eduardo, who only managed to tame the beast completely after the impressive knockout of Thiago Silva. “Before that, I would beat on the guys and they would keep coming. Eduardo increased my gas and the power in my hands,” acknowledges Lyoto.

Samurai in love

Behind every great man there is a great woman. Even though it sounds a bit chauvinistic, it makes sense when we hear the story of Lyoto and Fabíola Machida. “I take care of everything for Lyoto, I do everything to allow him to forget about our problems and just train,” explains Mrs. Machida. Their story started when they were 15 years old in a school in Belém.

“What enchanted me about Lyoto is that he didn´t look at me like other boys did, so I told him that I wanted him to be my boyfriend,” remembers Fabíola, who left school disappointed that day. “Lyoto wanted to court in the Japanese style, and asked me for two days to give me the answer. When the day had come he said ‘wait for me outside of the school’. He left me there waiting for almost an hour, when I was about to leave he showed up and said ‘stay here, we will date’. Since that day we have never separated,” laughs Fabíola, holding her son Tayo, who is one year old, in her arms.

But their story was not as easy as in the movies. To realize his dream of becoming the best fighter in the world, Lyoto had to leave Fabíola a couple of times. “In 2000, he got a Japanese manager who took him to live in the USA. This guy didn´t want him to get married with a Brazilian girl, he wanted a Japanese girl for Lyoto, but when Lyoto began to fight in Jungle Fight, we got married secretly and he took me with him to the USA. I stayed there in hiding for three months, but when his manager found out, he said Lyoto couldn´t stay in the USA anymore. We returned to Brazil and he sent Lyoto to Japan without me. We went for more than a year without seeing each other. It was crazy, we cried a lot on the telephone. I did everything I could to help Lyoto to achieve his biggest dream,” she says. Talking about the experience still makes her upset.

Even though she is a nice, delicate woman, Fabíola knows how to be tough. In Lyoto’s first fight in the USA (against Vernon White in the WFA), the promoter couldn’t send a ticket to his father and she was left to be corner woman for him. “He was a little bit worried because it was the first time he had ever fought in an octagon. I felt that and immediately turned into a man and told him, ‘you are in great shape, you are going beat this guy up’. At the bottom of my heart, I was much more insecure than him, but at that moment, I didn´t show it,” remembers the warrior lady.

But concerning nerves, Fabíola has no doubt in pointing out the worst day of her life, the day he fought for the title against Rashad Evans. “I’ve never been like that. I couldn’t stop shaking and crying. I got even more nervous after I saw Rashad’s KO’s on UFC Countdown. When Lyoto knocked him out, I just couldn’t believe it. I screamed, I cried, I kissed the television. Until today I still haven’t completely recovered my voice”, she says.

After going through all this stress with her husband, it would be expected that she wouldn’t like it if her son decided to be a fighter, right? Wrong. “I would love it if Tayo decides to be a fighter, but at the same time I would get worried because it’s a really hard life, and if he decides to follow his father’s steps, I’ll be there supporting him all the time just like I did with Lyoto.”

Local hero

Upon returning to Belém, Lyoto was received as a hero. Considered one of the poorest states in Brazil, Pará had never produced a world champion in any sport. “Soccer is the most popular sport here, but both top local teams are playing in the third level of the national division, so the entire city stopped to see Lyoto´s fight. When he won, it was like a world cup had been won, there were fireworks in the sky, people screaming. So when he arrived in Belém, he was received as a hero,” remembers Fabíola.

“Someone told me that a big celebration was being prepared for me, but I had no idea that it would be that big,” says Lyoto. “I left the airport in a fire truck, people in the streets screamed my name. It was raining a lot, but people stayed out on the streets celebrating anyway. I will never forget it.”

Because Pará state has the third biggest Japanese colony in Brazil with 30,000 immigrant descendants (São Paulo and Paraná are first and second), Lyoto was also invited to receive a special honor from the Japanese consulate. “It was amazing. We had more than 400 Japanese descendants at a special dinner in the auditorium of the Nippon Institute. They said I was a big pride for Japan and I was really moved by that,” he recalls.

Machida’s Japanese heritage means a lot to him. His father’s stern yet loving guidance has shaped him into the man and fighter he is today. “My father always taught me to keep going and never give up. He always says that in the fighter life you are always alone, it is the samurai way, and he always passed this to us, this Eastern philosophy – to make a man who could not only fight in the ring, but furthermore, fight in life.”

Family is everything to Lyoto. With three generations together for this special dinner, it is poignant that Machida should reveal that even though he has fought on three continents and trained with some of the biggest names in the business, everything he needs is right here in Belém. “I traveled all over the world and found what I was looking for right here in my home town,” he says.

“In school, everyone spoke only of jiu-jitsu. We would say that Royce´s jiu-jitsu was very good, but that our karate was also good, that there was space for everyone, but it made no difference and some friends who were into jiu-jitsu would always show up to test us.” At the time, Lyoto, who was about 15 and had some experience in judo and jiu-jitsu, was chosen to do the honors of the house. “He wouldn´t let anyone grab him and kicked their asses, so people began to say that our karate was different and we came to be respected in Belém,” recalls Chinzo.

The bones of Count Koma

It was in the city of Belém that the Japanese immigrant Mitsuyo Maeda (also known as Conde Koma, meaning Count Combat) taught jiu-jitsu to the Gracies, making possible the creation of the UFC and the future MMA explosion. We could not fail to ask Lyoto’s father about the fact that he chose to raise his children in the city where George Gracie (father of Carlos and Helio) and Conde Koma met. Machida's answer surprised us.

“15 years ago the tomb of Count Koma fell apart because of the excessive rain. I went there and took his bones, brought them home, cleaned them with steel wool and, with the help of the Brazilian and Japanese Association of the University of Kokushikan, succeeded in getting donations to put to the tomb back together,” said the karate master. To Gota Tsutsumi, coordinator of the Japanese-Brazilian Amazonian Association, Lyoto´s strength in the ring may be related to the fact. “The samurai spirit of Koma must be together with Lyoto,” he said.

A not-so-secret family secret

Machida has been the target of many comments from fans and fighters due to the unusual drink he takes every morning: his own urine. “You will not get extraordinary power from drinking your own urine, but it will protect your body from a lot of things and make you feel good, just like I feel,” says Lyoto.

Urine therapy is a practice that goes back thousands of years and appeared in cultures across the globe. Everyone from the Romans to Islamic holy men have partaken in drinking the amber liquid. “There are several vitamins that the body could not absorb from the previous day, when you take your morning urine they are reabsorbed, after I began to do this, I have never had flu or had jet-lag problems,” explains Yoshizo, who incorporated the method after reading a book on the second world war. “The Japanese discovered this technique when the drugs ran out, and eventually they began to drink their own urine and none of them got sick.”

At the end of our meeting, the Machidas did not hesitate to attend our request for a toast. The idea was just a toast for a quick photograph, but the Machidas, after having worked hard to ‘produce’ the liquid, did not want to waste it, even though they had already had their morning dose!