Issue 051

June 2009

Though there are arenas full of screaming fans and millions of people watching MMA on TV around the world, it’s easy to forget just how young the sport of MMA is. Football, athletics and even motor racing can boast layers of professionals working behind the scenes to improve every facet of a sportsman’s performance. The support structure that elite athletes can count upon is extensive to say the least, and though top MMA fighters are now bringing in various specialists to take care of their performance, unlike other sports there still exists a void.

The specialists who work with elite athletes have hard, reliable data to work with before even meeting their clients, but this data simply hasn’t existed in MMA – until now. Karl Tanswell, an MMA coach in Manchester, England, contacted a team based at Manchester Metropolitan University and asked them to work with one of his fighters, professional up-and-comer Matt Inman.

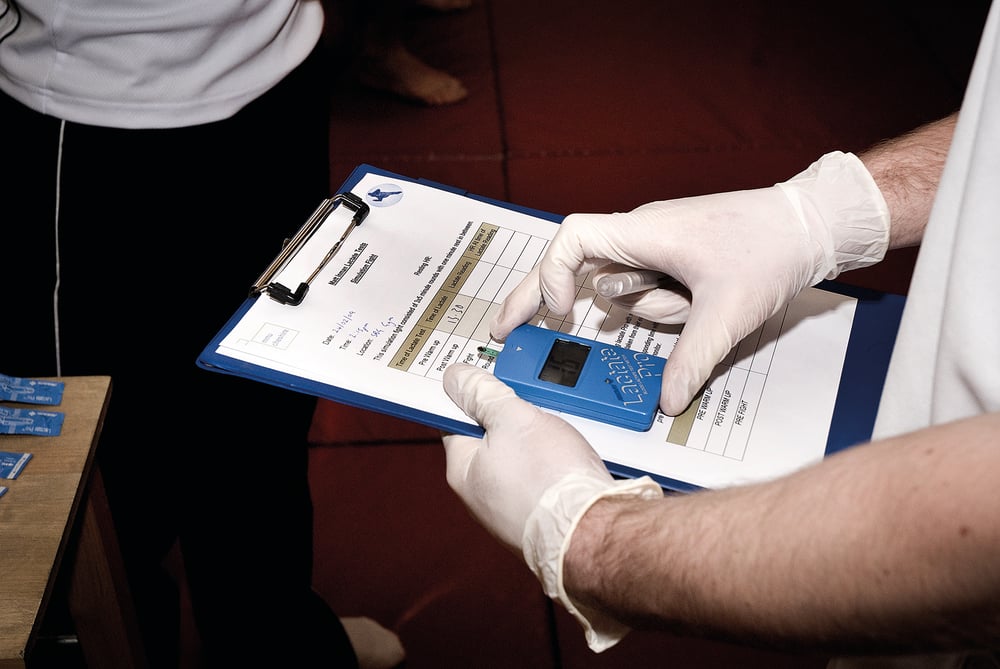

Dr Chris Morse and his team headed down to the gym for what was believed to be a world first. They analyzed Inman’s body during three rounds of work: a five-minute round of full MMA; a five-minute round of MMA simulation training (pad, bag and floor bag work); and a final five-minute round of MMA, with only one minute rest between rounds (to simulate a fight as closely as possible).

Fighters Only was there to witness this world first, although our man ended up getting a little closer to the action than expected. “No-one else was there for the session, so I ended up jumping in as the body for the MMA rounds,” said Percy, who is himself no stranger to the cage. “I didn’t expect to get my nose broke though!”

“Chris was really into it, he said nothing’s ever been done like this before,” said Karl Tanswell. The team had to deal with some unexpected factors during the MMA rounds though, which Karl laughs at. “The room was covered in blood,” said Karl. “I don’t think they were expecting that!”

Interview with Dr Christopher Morse, Dept of Sport and Exercise Science, MMU

What was the premise behind this work and why did you choose to do a case study on MMA?

At the moment there is no normative data on MMA fighters; nothing to show how hard these guys work during a fight. For most other sports, and wrestling is the best surrogate we have, there are heart rate, oxygen uptake, and lactate profiles during an event and during training, on participants from national to international level. So any training guidelines have to be based on ‘best guess’ scenarios about what is physiologically happening.

Why do you think that is? Do you think it’s maybe because the sport is still in an embryonic stage and so has not yet ‘socially qualified’ in importance for this type of study?

Embryonic is a great word! With people like Karl [Tanswell] on the ball we’ll get to fetal. The structure of scientific support in the UK is based around commercial funding or funding associated with success in the Olympics.

So, for example, scientific support is based at regionalized training centers or at large sports clubs. Unfortunately for MMA there isn’t the financial structure to pay for high-level support. The large promotions appreciate how valuable the fighters are as ‘commodities’ and treat them accordingly with medical support. But for the likes of Matt Inman; he’s in the hands of his coach and the resources available to him.

Do you think that to a certain extent this research was to ‘prove a point’, to show exactly how hard people are working, and how this stacks up against data from full-time professional sports?

A lot of the time it’s to prove to the fighters that they are ‘elite’ athletes, to give them the recognition of the work they put in, and to obviously develop and focus their training based on what we find. In this case, it was as a means of validating Matt’s training paradigm, to show that what they’re doing is highly specific to the demands of the sport, and to allow Matt to see that the way he focuses and remains motivated for training is both successful and appropriate for his level of competition.

What did you initially think / hope your data would show, and how did the actual findings differ from your pre-conceived ideas?

I would have thought, and indeed it was confirmed, that the training intensity, as shown in round two by elevated blood lactates, of the training circuits carried out by these fighters – such as Matt’s program and the stuff you see on UFC All Access – is physiologically harder than a fight round.

I’m not suggesting that training is harder than fighting. Psychological factors add to the stress in a fight to elevate the demands on the athlete, and it may be detrimental for the fighter to wade blindly into a match like he would in a training circuit. We had to show that these mimicked the stress on the athletes, and the heart rate and lactate data certainly verifies this. It was also important to follow the recoveries between rounds, and we were blown away in the lab by Matt’s recovery profile following anaerobic sprint testing.

Are you saying that you saw a spike in heart rate and lactate in the fight rounds due to mental pressure?

Not exactly, the circuit round, round two, showed a much higher blood lactate than the fight rounds. This implies that the physiological stress of Matt’s training far exceeds what he’d experience in a fight. But it’s important to acknowledge that in a fight he has an additional psychological stress, and he has more things to consider, and so it would be natural that his training rounds would be more intense as he can push himself as hard as physically possible without the potential of making a mistake, as he could do in a fight.

Does recovery testing only show cardio capabilities?

The ability to get oxygen to the muscles at the onset of a round referred to as ‘oxygen deficit’ is dependent on a wide range of cardiovascular and peripheral (muscular) factors. The faster the fighter responds, the lower the accumulation of lactate and anaerobic by-products, which are substances that can cause greater levels of fatigue and impair performance. After the rounds the ability to clear hydrogen and re-synthesize ATP will determine how successful the fighter is to recover for the next round. Athletes such as Matt show rapid oxygen uptake and rapid recovery associated with the numerous training adaptations: increased cardiac output, increased aerobic mechanisms in the muscle, vascularization, etc.

Can you explain in layman’s terms the different processes you used to collate the data, how specific they are, and how much do the results depend on the individual’s genetics as opposed to work ethic?

The team from MMU [Manchester Metropolitan University] were assessed on their ability to collect data and their interaction with Matt as an athlete. They extracted the heart rate data at five-second intervals and collated this with the activities he was carrying out and the blood lactates. They also transcribed a psychological interview and are actually preparing a highlight reel video for motivational purposes.

Make sure they edit out where I get my nose broken and just use the spinning back-fist, OK?

That was a wake up call for them. I think at that point they realized it’d be different than testing a runner, especially when they had to deal with the lactate blood testing, and the stuff was splattered all over the mats! But regarding genetics, obviously it has two major roles. It determines someone’s innate physical abilities, how strong they are and their lung capacity, but it also determines how well they respond to a training stimulus.

What differences do you see in the final data compared to a runner or soccer player. How do you compare?

It’s impossible to compare with a footballer (soccer player). I’ve not got the data to hand, but throughout a 90-minute match, less than 5% of the time is spent in a high-exertion state, with the remainder spent moving for position and at low-intensity running while another member of the team does the high-level stuff.

In the case of MMA, there’s no one to pick up the slack; the fighter has to work at maximum output for as long as possible. His success is dependent on him out-working his opponent and on setting a level that his opponent can’t match. From the data we saw, that’s certainly the case.

Do the final results give indications as to what aspects of training are more valuable to the ‘fight’ situation?

It’s really difficult to say what’s more important. The data we have shows that circuit-style training, the high-intensity continuous activity, is as specific as you can get. Essentially, Matt works at his highest level for as long as possible, as hard as he can for as long as he can, psychologically driving his physical attributes to reach their full potential. But in order to get to that high level he has to focus on specific adaptations before the endurance within the rounds, which his why Karl supplements the circuits with power and strength training at different points in his periodized training program.

How do we draw a conclusion to all this?

I think this whole research is just part of the process of MMA being perceived as ‘legitimate’. This sport of ours has a massive potential for growth and, as some have shown, for financial gains, and it was only a matter of time before people like Karl took the sport to the next level, realizing that behind every fighter is a team of people.

A Nascar driver couldn’t get round the track with just some petrol and a spanner, and it’s the same with a fighter. Ideally, they need a psychologist to develop their focus and motivation, a bio-mechanist to identify how they move and find weaknesses in their training movements, and a physiologist to identify how hard they’re working and ensure they reach their potential.