Issue 035

March 2008

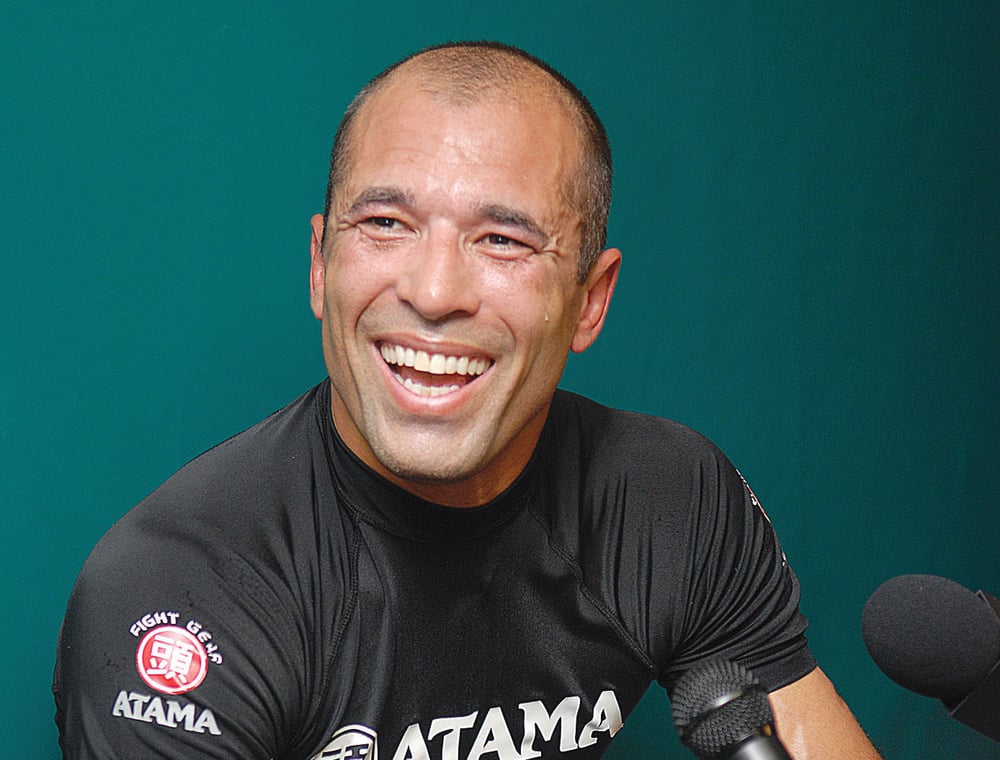

As he looked at his opponent across the ring before the fight, Rodrigo ‘Minotauro’ Nogueira may have wondered whether he was about to be run over by a truck for the second time in his life.

It was an evening in August 2002, and the event was Pride Shockwave in Tokyo. Nogueira faced Bob ‘The Beast’ Sapp, an insanely well-built former American football player who stands at 6ft 5in, yet looked almost as wide as he was tall. The fight that followed became one of the most famous spectacles in MMA history. Nogueira quickly shot in to take down Sapp, who countered the standard way with a sprawl. Then Sapp did something unthinkable outside the choreographed world of professional wrestling – he grabbed the Brazilian around the waist, lifted him up upside-down and dropped to his knees, drilling Nogueira’s head into the canvas with a piledriver.

Nogueira was dazed, but he hung on. He was slammed, clubbed with forearms, punched in the head and kicked in the face, but he kept hanging on, he kept attacking and working for submissions.

The end came from the same position as the fight began. In the fifth minute of the second round, Nogueira was again on all fours underneath Sapp. By this point the giant was far too tired to lift and slam him. Nogueira used a wrestling move called a ‘sit out’ to get behind Sapp, who fell to his side, exhausted. He offered little resistance as Nogueira levered his left arm into a straight armlock, one of the classic jiu-jitsu submissions.

Within Pride, Nogueira beat fighters such as Dan Henderson, Mirko ‘Cro Cop’, Josh Barnett and Heath Herring among others. Only Fedor Emelianenko, who many believe to be the best fighter in the world and to whom Nogueira lost twice by unanimous decision, proved to be his superior.

Few other Brazilians from jiu-jitsu backgrounds have had anything approaching Nogueira’s success in MMA, yet Brazil has had plenty of other talented Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) black belts who have been eager to make it in the sport over the last ten years.

All this begs the question: why do some Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu fighters, such as Nogueira, succeed when they make the move from the mats to MMA, while others fail?

One answer is blindingly obvious. As Nogueira’s fight with Sapp illustrated, if you want to succeed you have to be able to take a shot. Nogueira is as hard as nails, and was already demonstrating the indestructibility that has served him so well in MMA back when he was 11 years old by surviving being run over by a truck.

Ze Mario Sperry trained with, and coached, Nogueira at the Brazilian Top Team gym in Rio for eight years. “He doesn’t mind getting punched,” he says. “He’s got a strong head. He gets hit on the ground and he doesn’t mind, he’s very relaxed. For him MMA is like fighting a submission fight – but with punches.”

Another important factor becomes clear when you take a good look at the nature of jiu-jitsu competition and training. BJJ is a technically labyrinthine art, and all but the most exceptional practitioners handle the complexity by concentrating on developing their skills at a particular game. Broadly speaking, BJJ fighters fall into two categories: those who like to work from the top, and those who like to work from the bottom.

Top fighters concentrate on taking their opponents down and passing the guard. Bottom fighters are guard experts, and look to sweep or submit from that position. When top fighters make the transition from BJJ to MMA, they face a big challenge. Until now they will have fought opponents with relatively limited wrestling skills, some of whom will have willingly given them the top position (bottom fighters), yet now they have to fight opponents with wrestling skills of a calibre they are unlikely to have encountered before, and who can punch, kick or knee them as they shoot in for a takedown or clinch. Suddenly it becomes difficult to get an opponent down to the ground and begin working from the top, which means top fighters are going to have to develop their second-string game, working from the bottom.

On the other hand, bottom fighters come to the cage or ring with skills that translate readily. They are already skilled at trying for submissions from underneath – which is where they are likely to end up when they confront opponents with better wrestling skills. It comes as no surprise that Nogueira is (and always has been) a fighter who likes to work from the bottom. “He is the only man in the world in MMA until now that can really fight jiu-jitsu with his back on the ground,” says Sperry. “He is the one who can show the true jiu-jitsu in the best way.”

Changes in the rules of MMA have had a huge effect on the fortunes of fighters from a BJJ background, and have further defined the type of game they require. “They are succeeding a little less than they should because of the changes,” says Luca Atalla, editor of Gracie Magazine, Brazil’s top jiu-jitsu publication. Under the widely-adopted unified rules of mixed martial arts, referees restart a bout from standing if fighters are in what they consider to be a stalemate position. The days are long gone when refs will tolerate the type of patient strategy with which Royce Gracie attempted to beat Ken Shamrock at their UFC Superfight in 1995, when Gracie held Shamrock in his guard for minutes on end.

Today’s rules ask for continuous action, and they can come as a culture shock to jiu-jitsu players who have worked their way up through competitions in which referees allow players to work on the ground with no hurry. Atalla is optimistic that the jiu-jitsu community will soon catch up with the rules. “Jiu-jitsu makes you adapt yourself to the rules no matter if they are bad to you. The jiu-jitsu mentality is the key. If you have the mentality to win whatever the environment, the techniques will come later.”

Whatever strategies the Brazilians develop in the future, one thing is already clear: In order to succeed they must either have, or develop, an uptempo, aggressive game.

Fortunately for Nogueira, he has always had just that. Atalla has followed Nogueira’s career since his kimono days. “His game was always to try to submit his opponents,” he says. “He always tried to make fights very fast, and he moves a lot. So when you translate that into an MMA fight, you see that as you move, if you are more technical in your moves than your opponent, some time in the middle of the fight you are going to be ahead of him. That’s the reason I see Nogueira beating so many opponents.”

Even with the best submission skills in the world, fighters are not going to deposit winner’s cheques in their bank account on the Monday morning after a MMA bout unless they have some mastery of the art of hitting, and not being hit. “Sometimes jiu-jitsu fighters face trouble because they don’t know how to fight standing,” says Sperry. The striking element of MMA makes it a completely different sport from jiu-jitsu, which sounds like an obvious thing to say, but the message still doesn’t appear to have sunk in properly in some circles in Brazil.

“The transition is tricky, and the most important thing is whenever jiu-jitsu fighters get the fight on the ground, they have to understand it’s not a submission fight,” advises Sperry. “Even though you are on the ground, it’s an MMA fight. The punching aspect makes it totally different. Most jiu-jitsu fighters are not used to getting hit, so they are not comfortable. Sometimes they lose their goal, they lose their strategy, they get nervous, they get a little bit tired, they get a little bit stupid.”

Some notable BJJ exponents (Royce and Royler Gracie among them) have never developed convincing striking skills, and can be classified as jiu-jitsu fighters who compete in MMA rather than well-rounded MMA fighters from a jiu-jitsu background. Their approach has been to concentrate on taking the fight to the ground while learning enough to defend themselves on their feet and set-up a takedown, which is the classic Gracie way. But those who adopt this strategy are becoming increasingly marginalised as the sport evolves.

In order to make a real challenge for any of the MMA titles, jiu-jitsu fighters have to be prepared to leave their comfort zone and learn to dish out punches and kicks effectively, as well as defend against them. Marcio ‘Pe De Pano’ Cruz is doing just that. The former BJJ heavyweight world champion has entered the Octagon four times, and has his sights set on the UFC heavyweight title. “Whatever I do I strive to be number one,” says Cruz, who is a member of the Gracie Barra Combat Team (GBCT) based in Barra, Rio. Cruz agrees with Sperry that it’s hard to make the switch to MMA. “It’s very difficult to transfer. You have to prepare yourself physically in a different way. You lose some jiu-jitsu, you have to train stand-up, you have to train everything. Even when you learn boxing, Muay Thai and wrestling, MMA is still a different art. It’s difficult to put them all together.” Yet Cruz has been energised by the challenge of trying to succeed at the highest level in a new sport as Dennis Asche, a fellow GBCT member, attests: “When he started training, he wasn’t so serious, but he’s really motivated now. He goes to all the boxing classes, runs up Pedra De Gavea [a steep nearby mountain].”

On paper, Roger Gracie looks like he has the potential to become one of the better MMA fighters to emerge from jiu-jitsu in recent years, and in December 2006 the heavyweight from Gracie Barra UK got off to a great start by submitting the tough wrestler Ron Waterman with an armlock from the guard in his debut. Gracie has a complete game: he can fight from the bottom and the top. “Technically speaking, Roger is the best I have ever seen,” says Atalla. “Genetically he is good as well, because he’s tall, he’s heavy, and his endurance is very good. Mentally he is good. He doesn’t give up, so he has everything to be successful as an MMA fighter. But we have to see if the violent environment will be suitable for him. There’s still a question mark. We will see if he is good enough only after he passes through a very hard situation in a fight.”

Nogueira demonstrated he had what it takes when he was severely tested by the behemoth Bob Sapp. Other fighters from BJJ backgrounds who want to emulate his success will have to show that they are not only tough, but also have slick, offensive skills from the bottom and can throw a decent punch.

Paulo Filho

After Nogueira, Filho is probably the best BJJ stylist in MMA. Tough and aggressive, he almost breaks the typical jiu-jitsu fighter mould in that he has good throws and takedowns and consistently puts his opponents down to work a powerful and devastating game from the top. But Filho didn’t quite have the takedown firepower to dump the wrestler Chael Sonnen in his WEC fight in December, and had to again prove he has excellent skills from the bottom by armbarring Sonnen from his back.

Marcelo Garcia

An incredibly gifted jiu-jitsu fighter who has been a sensation at the ADCC Submission Wrestling tournaments, Garcia made his first foray into MMA against judoka Dae Won Kim in K-1 last October. Round one looked like business as usual for Garcia as he took Kim down and took his back, working a methodical attack but unable to find a finish. At the beginning of round two Garcia demonstrated naivity in his stand-up game by failing to see a telegraphed knee that badly cut him and led to his demise. It remains to be seen whether Garcia will turn out to be another Brazilian with great ground skills and average stand-up, or whether he can transcend his current limitations and become a competitive MMA fighter. Hopefully his current training with the renowned American Top Team will ensure he is of the latter.

Ricardo Arona

A huge natural talent, Arona could go to the top, says Sperry, if only he applied himself more. “He doesn’t train much,” says Sperry, who used to be Arona’s teammate at BTT. “If he trained like Nogueira, he’d be unbeatable.” Arona is fast, powerful and has a great ground game, yet with only two wins by submissions in 18 fights, he needs to become a better finisher.

Nino Schembri

One of the jiu-jitsu greats, Nino ‘Elvis’ Schembri famously caused an upset by TKO’ing Kazushi Sakuraba with in Pride in 2003. But four straight losses followed, including a return match against Sakuraba, and despite that victory over the Japanese legend and time spent training with Chute Boxe, Schembri still lacks a stand-up game. Now part of the Black House team, Schembri still has to prove he has what it takes to make a successful transition from BJJ to MMA.

Jorge ‘Macaco’ Patino

Nick-named ‘Monkey’, this grappler has a style reminiscent of Paulo Filho. A stocky and strong player, he is versatile and can play from top or bottom. Of his 33 fights, he has won seven by submission and seven by stoppage, evidence he has adapted his grappling background for the ring and cage.

Ronaldo ‘Jacare’ Souza

Entering MMA in 2003, this former BJJ world champion lost in his debut and learned the hard way that grappling alone is not enough to compete in MMA. Since then, the middleweight has combined his excellent judo and wrestling skills with his world-class jiu-jitsu to rack up seven straight victories.

...