Issue 053

August 2009

Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, David Beckham, Roger Federer: when will we see the name of an MMA fighter join this list of high-powered and highly endorsed athletes?

Photo credits: Gong, FEG, Zach Lynch

Five years ago, that question would have been considered ridiculous, as MMA was still viewed as too risky by the majority of corporate America. It seems times are changing.

Though MMA is still relatively young its popularity has grown exponentially over the last few years. Many argue that it is in fact the world’s fastest-growing sport. Whether or not this is true, there’s no doubt that the attitudes of the corporate world have begun to shift as, each day, MMA moves further into the mainstream. This is of course great news for the fighters, who have not only seen a rise in salaries but also in sponsorships, endorsements and other commercial opportunities.

In recent months, companies such as Gatorade and Nike have taken a keen interest in MMA, resulting in landmark deals being penned between them and UFC welterweight champion Georges St Pierre (GPS). The French-Canadian is the first UFC fighter to have achieved a mainstream corporate endorsement, largely thanks to his signing with the Creative Artists Agency, a talent agency currently managing licensing, sponsorship and endorsement opportunities for the likes of David Beckham, skateboarding legend Tony Hawk and basketball star LeBron James.

The Montreal native may be the first; he will definitely not be the last UFC fighter to receive a mainstream sponsorship. Former light heavyweight champion Rashad Evans has signed a deal with Microsoft, and it seems other UFC stars are in talks with the likes of Harley-Davidson, Bud Light and Bacardi. So when can fans expect to see MMA fighters as big as their athletic counterparts in more traditional sports?

“When I see a sponsored fighter like GSP, decked out from head to toe in Nike gear, it makes me wonder whether or not we’re already there,” says renowned MMA manager and agent, Ken Pavia. “It’s a great development. For the fighters, it’s been a long time coming. It just goes to show how much the sport has grown. Corporate America is no longer scared of this thing, they’ve realized just how popular it is.”

Not only do sponsorships help with mainstream recognition, but they also act as a secondary source of income, pushing fighters’ pay figures closer than ever to those of other athletes (although still not comparable). Jervis Cole, Evans’s manager, claims his charge will make between $700,000 and several million dollars due to sponsorships and endorsement deals this year. Unfortunately, those sums are out of grasp for the majority of fighters, but being a UFC superstar certainly helps.

“For the majority of fighters, sponsorships are just the icing on the cake,” says Pavia. “It’s a bonus.”

According to Pavia, the average UFC, Strikeforce or Affliction fighter can at best expect to double his earnings through commercial opportunities. Though this may sound like a lot, it’s mere peanuts when compared to the sponsorship and endorsement deals readily handed out to mixed martial artists in Japan and Korea, where the likes of KIA, Samsung and Nike have been sponsoring fighters for years. Rumors have it that even Coca-Cola, who in the past had a policy of not sponsoring anything violence-related, are getting into the game. However, unlike in the West, sponsorships don’t always rely on a fighters skill but more their marketability.

“In Japan, it’s on another level,” says former Pride commentator Mauro Ranallo, a frequent visitor to Japan. “Wanderlei Silva was the spokesperson for Udon, a fast-food noodle chain; Caol Uno has his own very successful clothing line. Everyone’s got something. It’s not uncommon to see a fighter’s face on billboards and TV commercials. Often they’ll organize sponsored media events, with fans showing up in thousands to meet the fighters.”

The predominant reason for this is the fact that Japanese MMA is regularly broadcast on free TV, resulting in viewing figures unheard of in the West. While some like to claim that the golden age of Japanese MMA is over, there’s no denying that, to this day, fighters in the land of the Rising Sun are nothing short of celebrities, and their incomes are proof.

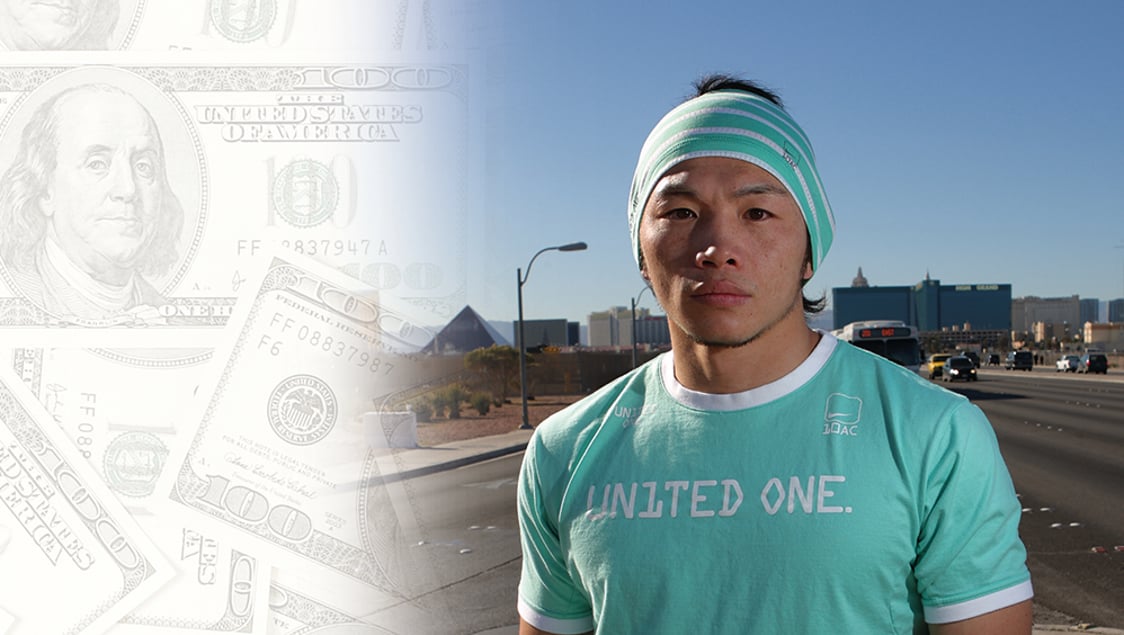

Japanese-Korean middleweight Yoshihiro Akiyama is the perfect example of a fighter who has attained nothing short of superstardom in both Japan and Korea. Recruited by FEG (DREAM’s parent company) in 2004, Akiyama was chosen to be their first big Korean star. With his good looks, FEG marketed him towards a female fan-base, resulting in myriad TV appearances, magazine covers and other commercial opportunities, netting him millions. The former Judo world champion has starred in everything from car to beer commercials, including two particularly stylish spots for automotive giant KIA.

“Akiyama’s huge,” agrees Ranallo. “Especially in Korea. In Japan, I’d say he’s next to Kid Yamamoto in presence. But when it comes to sponsorships and endorsement, you can’t beat Bob Sapp.”

At 6’4” and 380lb, Bob ‘The Beast’ Sapp is a sight to behold. Albeit the former NFL player’s MMA record is by no means impressive, his immense physique and showmanship made him an instant hit in Japan, where he fights in both DREAM and K-1.

Though not a top fighter by any stretch of the imagination, Sapp’s proven to be extremely marketable, resulting in over 400 endorsed Japanese products. In Tokyo, shoppers can buy everything from Bob Sapp watches, to cereal, to a sex toy called (wait for it) ‘The Big Sapp’. As if that wasn’t enough, he has also released a rap album, entitled ‘Sapp Time’. Oddly enough, it made it to number 18 in the Japanese charts.

“You name it, I’ve done it,” said Sapp in an interview with the Seattle Times. “Back home, I’m unknown. In Japan, I can’t get away from the fans. I never expected anything like this.”

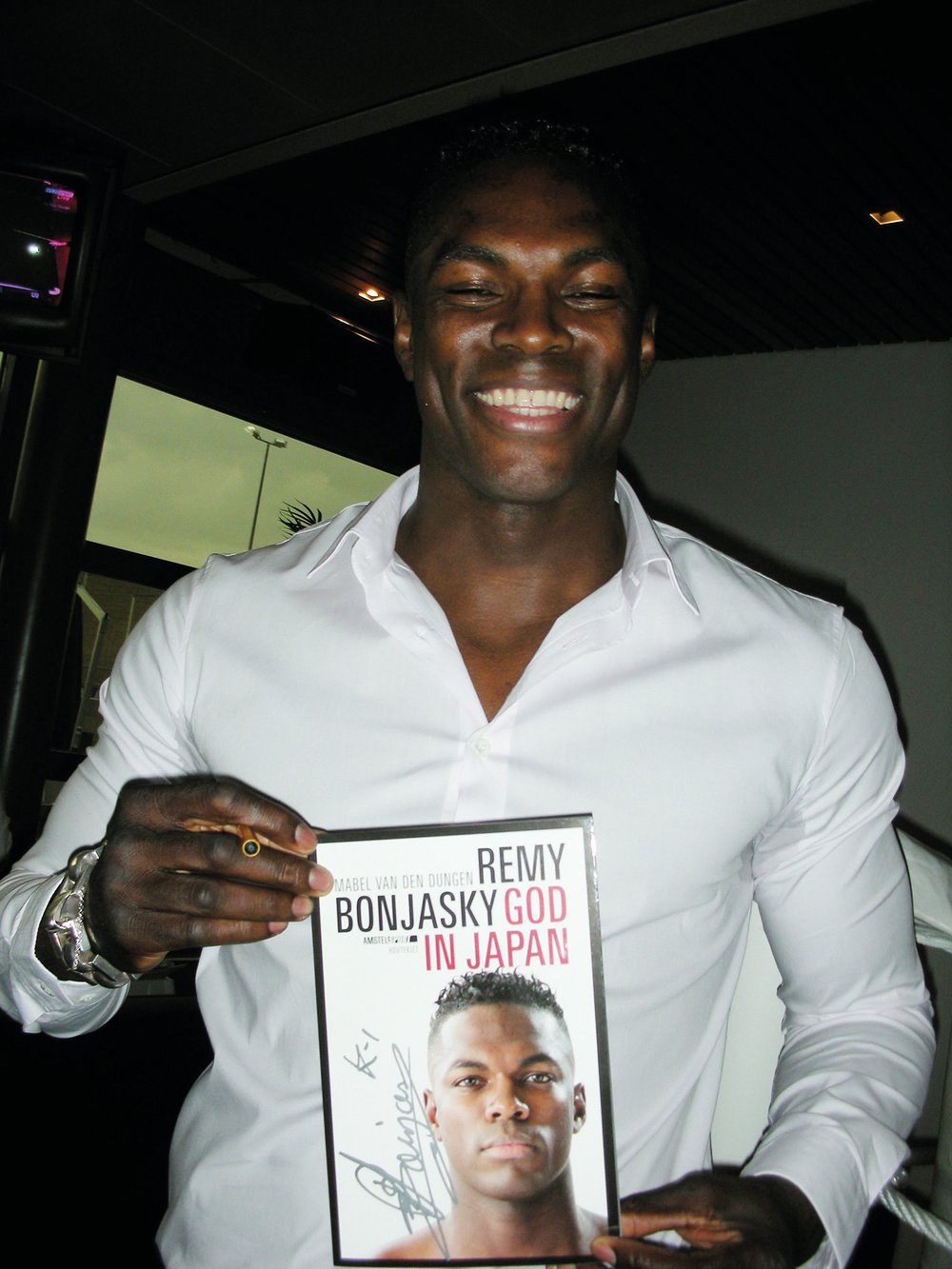

Other K-1 fighters have also experienced a similar phenomenon. Three-time K-1 world champion Remy Bonjasky is a B-level celebrity in his native Holland, but the top-tier kick boxer is an absolute star in Japan, with several big sponsors and endorsement deals.

“I hired a manager to take care of all the commercial opportunities,” says Bonjasky. “I wouldn’t need to do that in Holland, because the chances are few.”

Fighters may not see these types of endorsement opportunities in the West, but other options have proven quite viable in recent years. For one, it seems TV, film, and video game appearances have become a legitimate secondary source of income for many American mixed martial artists. Gina Carano, the face of female MMA, has been particularly successful, with a spot on hit NBC television series American Gladiators.

The Dallas County native also starred in top selling video game, Command and Conquer: Red Alert 3. “Whenever I’m not fighting I like to have other projects,” says Carano. “Fighting is my career, but I need other things to keep me busy when I’m off training, or waiting on a fight.” The majority of top American fighters share Carano’s feelings on the matter.

“Fighters should get paid to do one thing: fight,” says Pavia. “All of the top guys are very focused on their careers, and don’t necessarily have time for anything else.”

This is perhaps the biggest difference between Western and Eastern promotions as far as sponsorships and endorsement are concerned. The matchmakers of Japanese organizations like DREAM and Sengoku have one priority – to create highly marketable stars, as opposed to top-tier fighters. In Japan, marketability will also win over fighting ability, even if the fighter is seriously lacking in the latter. This is often the reason why certain mixed martial artists attain an unbelievable level of mainstream success, without fighting any kind of significant or regular competition.

While still not quite at the same level as their Japanese counterparts, American MMA promotions, especially the UFC, have begun to attain a high level of acceptance in the corporate world. A big contributor is the fact that the UFC clearly has the best fighters. When one has the world’s top talent, the big deals can’t be too far behind.

For the next generation of UFC fighters, the future looks bright.