Issue 022

February 2007

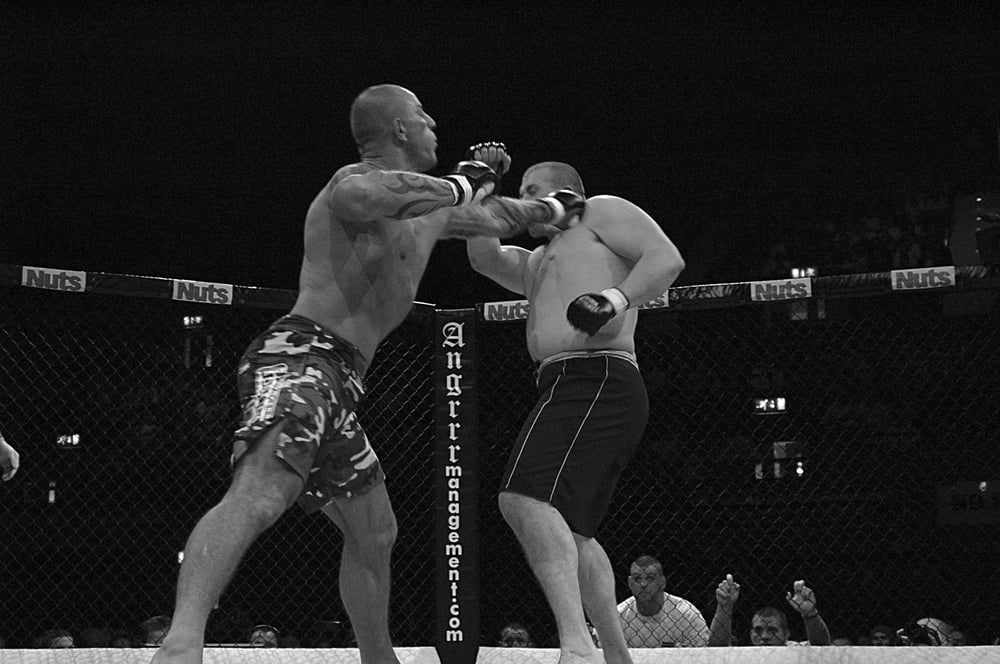

David West on how techniques of the London Prize Ring live on in modern MMA.

Saturday 28th September 1811 saw the most hotly anticipated rematch in the history of the London Prize Ring. The second set-to between Champion of England Tom Cribb and American former-slave Tom Molineaux, who had almost beaten the Briton in a thirty-four round war in December the previous year. According to the eyewitness account of Pierce Egan, the most celebrated chronicler of the prize ring, Molineaux threw Cribb to the floor in the third round:

“The superiority of the Moor’s strength was evinced by his grasping the body of Cribb with one hand, and supporting himself by the other resting on the stage; and in this situation threw Cribb completely over upon the stage, by the force of a cross-buttock.”

That doesn’t sound much like contemporary boxing, but was typical of the range of techniques seen in the day’s of the London Prize Ring. The cross-buttock, the chancery, milling in the clinch – just some of the techniques of old bare-knuckle pugilists long since passed into antiquity in terms of modern boxing. However they can be found in mixed martial arts, where they are better known as the hip throw, front headlock and dirty boxing. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

A common misconception among neophytes to the pre-Marquess of Queensberry rules is that the London Prize Ring contests were simply boxing without gloves. Except the form of pugilism, practiced by Cribb, Molineaux and their bare-knuckle brethren, was very different to what we see in modern boxing rings.

Fights took place either on a wooden stage, if held indoors, or in a ring constructed with ropes and stakes driven into the ground, when held outdoors. The end of a round was not determined by a timekeeper, but each round ended when either combatant was “downed”, meaning he had a knee upon the floor, was knocked down, or thrown. Thus a round could last seconds or drag on interminably when the combatants were stalemated.

Unlike modern boxing, but like MMA, mastery of the clinch was a vital part of the game. There were umpires to ensure fair play and each man had a second and a bottle-holder to watch out for rule infractions from the opposition. But there was no referee to break a clinch. The form of grappling permitted in the London Prize Ring was comparable to Greco-Roman wrestling, in that holds were only allowed above the waist. The favored technique for throwing was the cross-buttock, or what would be termed a hip throw in modern terminology. That said, Pierce Egan recounts many other throwing techniques, some of which were legally questionable under the old rules.

In a fight held on May 10 1808, John Gulley, then recognized as Champion of England, fought a rematch with a battler known as Bob Gregson, the Lancashire Giant. Gulley was the better technician, but Gregson, as his nom-de-guerre suggests, was the bigger and more powerful of the pair. Egan describes the action in the sixth round:

“Some severe blows passed, when Gregson rushed in and caught Gulley by his thighs, lifted him from the ground, threw him down, and fell upon him, nearly knocking the breath from his body.”

That sounds suspiciously like a double-leg pick-up leading into a slam, much like those performed in the octagon by Matt Hughes. Gregson used the throw to land on top of his opponent, common practice now. Although not all the pugilists of yore took such advantage, as seen in this account of the contest between Jem Belcher and a butcher-turned-brawler called Bourke:

“…they closed, and Bourke was thrown; when Jem, very honorably, fell upon his

hands, with an intent not to hurt Bourke anymore by falling upon him. Which practice is not unusual, and consistent with fair fighting.”

No modern boxer would consider being thrown on his head as fair fighting. However George Taylor, a pupil of James Figg, known as “the father of boxing”, was famous for his ability to win fights by slamming his opponents into the ground until they couldn’t continue. Pre-dating Quinton “Rampage” Jackson by 300 years. Taylor lost his crown as Champion of England in 1740 to Jack Broughton, who was responsible for codifying the rules of the London Prize Ring.

Holding and hitting was an accepted practice and could be a hurtful way to turn the tide of battle, described in a contest between Jem Belcher and his former pupil Henry Pearce, champion at the time of their meeting:

“…a rally ensued, when the advantage appeared on the side of Belcher; but, in closing, Pearce got Jem’s head under

his left-arm, and punished him severely with his right, when in struggling, both went down.”

Aside from the delicate art of putting someone in a headlock (or front

chancery) and bashing their face in, the pugilists of old had different targets to their modern counterparts in the squared ring. Where contemporary boxers aim for either the nose, the jaw, or a cut the eyes, classical pugilists aimed first for the side of the neck, just below the ear, what we now call the carotid artery, as their preferred target.

A blow to the carotid artery frequently resulted in a knockdown, although since combatants had thirty seconds to recover themselves, during which time they were helped by their seconds. Even a blow to this vulnerable region seldom brought a contest to an outright conclusion. Other targets included the bridge of the nose between the eyebrows, with the intention of causing eyes to swell shut, and body punches, often directed to the kidneys.

In a fight with Andrew Gamble, Jem Belcher finished him off with “one in the stomach that nearly deprived him of breath; and the other on the kidnies [sic] which instantly swelled up as big as a twopenny loaf. Gamble completely exhausted, gave in.”

A knockout worthy of Bas Rutten, the modern master of body punching, who loved to go downstairs with his striking and stopped Jason Delucia in memorable style in their third Pancrase match back in 1996. Melvin Manhoef, the Dutchman with thunder in his fists, loves to work the body to soften up his opponents, seen to great, if brutal effect, in his match with Fabio Piemonte at Cage Rage 13. A crushing punch to the midsection

opened up Piemonte’s defenses to set up the knockout blow to the jaw. By contrast, kidney punches are illegal in modern boxing.

A subject of debate in MMA, elbow strikes were illegal in the London Prize Ring, but that’s not to say they were never used. In his boxing manual, ‘Physical Culture and Self Defence’, published in 1901, former middleweight and heavyweight champion Robert Fitzsimmons demonstrates the infamous “pivot blow” as a useful tool for self-preservation in the face of hostility. While Fitzsimmons won his titles

under the Queensberry rules, he started his career as a bare-knuckle fighter and was fully conversant with all tricks of that harsh trade.

The pivot blow was used after missing a punch and involved pivoting on the heel to bring the elbow sharply back after the punch to catch your opponent on the jaw. In 1886 George La Blanche, using a pivot blow, knocked out the original Jack Dempsey, the nonpareil. After the match Dempsey was still recognized as middleweight champion, since La Blanche had used his elbow, not his fist, to score the knockout.

Backward elbow strikes are popular in Muay Thai and can be found in MMA arsenals of fighters like Anderson Silva, who knocked out Tony Fryklund with an upwards/backwards elbow when they fought at Cage Rage 16 A pivot blow performed without the set-up punch by the phenomenal Silva.

Since motion pictures post-dated the transition to the Queensbury rules of boxing, there are sadly no films or clear still photographs of the old pugilists in action. However, many of the fighters who rose to prominence after the adoption of the Queensbury system still employed techniques held over from the days of bare knuckles.

Both Bob Fitzsimmons and British Bombardier Billy Wells, British heavyweight champion from 1911 to 1919, were both bare-knuckle boxers. Wells threw his left from an upright stance, putting his weight forward on his lead leg to drive the punch home. Compare the photos of Wells demonstrating his “left-hand twist punch” from his 1912 book ‘Modern Boxing’ with that of MMA fighter Robert “Buzz” Berry. Their techniques appear almost identical.

On the subject of heavy hitters, few MMA champions can match the success of current UFC light heavyweight king Chuck ‘The Iceman’ Liddell. With a record, at time of writing, of 19-3-0, Liddell has a distinctive style, which in the language of the octagon is sometimes called sprawl and brawl.

Liddell is a stand-up puncher with knockout power in his hands and his tactics are tailored to maximize his strengths. Liddell stays on the outside, using footwork to keep his opponents from clinching or taking him down. This allows him to pick them off with his pinpoint punching as they are forced to follow him around the cage to try to close the distance. Liddell’s style is reminiscent of the single most celebrated warrior of the London Prize Ring and the man who retired while still Champion of England, Tom Cribb.

His particular style, which was unanticipated by any of his forebears who tended to relentlessly bore forwards hammering away, was calling milling on the retreat.

In October 1808, Cribb took on Bob Gregson who had unsuccessfully challenged John Gulley for the title in May of the same year. Despite his size and power, Gregson did not know how to deal with Cribb’s singular style, as demonstrated in Pierce Egan’s account of the third round:

“Gregson full of spirit rallied, and planted a most tremendous hit under the ear of Cribb, who retreated according to his favorite mode of fighting, and Gregson incautiously following him, suffered that severe punishment termed milling on the retreat, receiving a heavy blow on the right side of his face from every retreating step of his opponent, but still the game of Gregson kept him following close, till he fell quite stunned.”

Gregson managed to return to the mark in time, although Cribb repeated the same technique to score another knockdown in the eighth round, enjoying “considerable success from Gregson’s intemperate and injudicious mode of following him, who received such severe blows on his face, that he fell on his knees…”

If Cribb had been allowed to continue striking his downed target, no doubt the match would have ended there. However, since the London Prize Ring forbade fighting on the floor, Gregson beat the count and fought on until the end of the 23rd round, when he was finally, so badly beaten, he was unable to come to scratch (take up position to recommence fighting) before time was called.

Many of Liddell’s opponents have fallen victim to his own tactic of milling on the retreat, rushing at their man only to be knocked down in their impetuosity. Babalu is the most recent example and Liddell picked off even the great Randy Couture as he pursued him around the cage in their second and third encounters.

Liddell’s four-round demolition of Jeremy Horn at UFC 54 was a perfect demonstration of milling on the retreat. Liddell let Horn take the center of the cage, circling around the perimeter and punishing Horn every time he threw a punch, while evading Horn’s own

blows using his footwork. Cribb would have approved.

Combatants may no longer fight with their bare hands on squares of turf, but in spirit and sometimes in practice, the London Prize Ring lives on.

Sources:

- Egan, Pierce, Boxiana, or Sketches of Ancient and Modern Pugilism, 1812

- Fitzsimmons, Robert, Physical Culture and Self Defence, 1901

- Wells, Billy, Modern Boxing: A Practical Guide to Present Day Methods, 1912