Michael Bisping’s eyes probably light up if you say you love him, but he prefers it if you hate him, especially if you happen to be a fellow fighter and middleweight against whom a title can be defended and with whom money can be made. It’s easier this way. Not only is this scenario a familiar one for Bisping, and therefore by now his comfort zone, it is also, for as long as he calls himself a professional mixed martial artist, a lucrative one.

Essentially his USP, Michael Bisping is and has always been the man middleweights – and, occasionally, light-heavyweights – love to hate. It’s as much a guarantee as a Demetrious Johnson title fight being overlooked or a Jon Jones title fight being on a knife-edge. It was this way when Bisping first entered the UFC in 2006 and it’s certainly this way now, eleven years later, during a time when his ‘haters’ are forced, through gritted teeth, to address him as ‘champion’.

In recent weeks Bisping has endured the wrath of Yoel Romero, who took offence to Bisping ripping up a Cuban flag at UFC 213, and then Chris Weidman, who refused to say Bisping’s name after defeating Kelvin Gastelum on Saturday (July 22) but did make reference to a “British bum” he claimed was “hiding”.

Bisping is certainly British. We know this by now. It’s a label he wears proudly. He is also, despite the hate, the reigning UFC middleweight champion, a fact that has served only to spread and intensify the disdain. Bisping, after all, was a hate-able figure when he was a mere perennial contender winning and losing against fellow contenders and always just falling short of the big win he needed to secure a shot at the title. Now, though, with a belt around his waist and the volume of his microphone turned up to eleven, Bisping, the man who would not be denied, has, to those in pursuit of him, never seemed more intolerable.

Bisping knows this. It’s why he continues to harness it, work with it and enjoy it, rather than dilute his outbursts or be the bigger man. Being hated, you see, has never done Michael Bisping any harm. Even before he became champion, Bisping was making good money in the UFC not only because he was a company guy who helped build the sport in the United Kingdom, but because he was a polarizing figure whose demise many people would pay good money to see. For Bisping, this has always been the way. The 2009 knockout he suffered at the hands of Dan Henderson, for example, wasn’t just a win for the H-Bomb, it was a win for seemingly half of America, all of whom had been praying for Bisping’s comeuppance ever since watching him coach opposite their all-American hero on season nine of The Ultimate Fighter.

Indeed, so strong was the vitriol around that time, it’s testament to Bisping’s ability and belief that he even recovered from such a humbling defeat, let alone had the last laugh in the form of a UFC middleweight title. Silenced in every possible way, nobody would have begrudged Bisping scurrying away with his tail between his legs after being bounced off the canvas by Henderson. Nobody would have blamed him for going gun-shy and falling victim to an unsightly losing run, either.

But, instead, Bisping brushed himself down, continued to believe in himself, continued to talk shit when appropriate, and kept moving forward. He kept fighting. He won some, he lost some. One guarantee, though, was that Michael Bisping was eminently watchable. It didn’t matter whether he was winning or losing. It didn’t matter who opposed him. When Bisping was involved in a UFC event, you knew there’d be an angle, a story, something to sink your teeth into. The Brits call it “needle”. You knew there’d be needle.

This, of course, usually has everything to do with the fact the majority of the UFC’s middleweight division, for the best part of a decade, have appeared to hate the Englishman. It also, however, has a lot to do with the fact Bisping realises this and milks it to within an inch of its life. He plays on this ill feeling. He makes it work for him. A lot of the time, his opponent, the one doing the hating, won’t even realise. They won’t entertain the possibility that their hatred for Bisping not only motivates him but also does plenty for the 38-year-old’s bank balance and overall notoriety.

Presumably, when you beat Bisping, it feels great. There’s vindication, bragging rights, a feel-food factor, all up for grabs. It’s a victory shared and enjoyed by many. But if you lose to Bisping, God forbid, there can be no worse fight to go wrong. If in doubt, ask Luke Rockhold. He hated Michael Bisping with a passion ahead of their fight last June and could see no way the loud-mouthed Brit approaching 40 stood a chance of beating him in front of his Californian fans. Forget just winning, he wanted to teach him a lesson. He wanted to make it look easy. Expose Bisping. Humble Bisping. Humiliate Bisping. Finish Bisping.

So, with an arrogant smirk dominating his face, Rockhold sauntered through the title defence like a man who knew it was only a matter of time, like a man who knew he couldn’t be hurt, and visualised shutting Bisping up. He did this for approximately three minutes and thirty seconds, right up until the moment he suddenly found himself wobbled by the challenger’s counter left hook and put on his backside over by the Octagon fence. Rockhold, the ‘good guy’, was stopped inside a round and Bisping, the guy nobody liked, now couldn’t have cared less whether he was popular or not: he was, above all else, the UFC middleweight champion.

Interestingly, as a result of that win, the Bisping hate momentarily died down. Peers forgot their differences and congratulated him and fans recalled the longevity, the losses and the struggle and discovered a sentimental part of their brain was able to not only forgive Bisping for past indiscretions but actively praise him for persevering and finally getting his just desserts. The MMA world was happy for him. He fought Dan Henderson in his first defence and people didn’t even mind. There was the odd dissenting voice, sure, for Henderson was nowhere near the top ten and had lost six of his previous nine fights, but, for the most part, people were happy to give him a pass. It was Bisping. He deserved this. Give him the chance to get his revenge, they said. Give him a homecoming in Manchester. He has earned it. Paid his dues.

Bisping, because of this outpouring of goodwill, finally felt the love. He walked taller. He could relax and be himself. He then marched out in front of 20,000 countrymen to erase memories of the H-Bomb circa UFC 100 and retain his UFC middleweight title, a result that, given its context (Bisping overcoming demons, surviving two knockdowns), made a hero of a one-time villain.

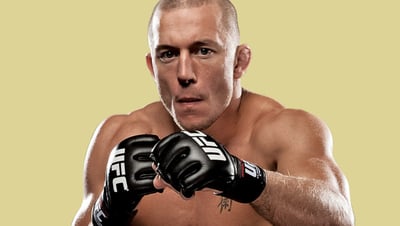

But that was last October. Nine months ago. Since then, the tide has again turned and Bisping has tried the patience and tested the love of mixed martial arts fans the world over with a combination of inactivity – granted, not entirely his fault – and a desire to pursue so-called ‘money fights’, the most notable of which is one against former welterweight champion Georges St-Pierre, in lieu of title defences against highly-ranked middleweights. This has dried up the goodwill of fans and also fellow fighters, some of whom are desperate to get Bisping into an Octagon and challenge him, perhaps even dethrone him.

This impatience isn’t just fuelled by hate. It’s also fuelled by a belief that Bisping is a beatable champion, one lacking the same air of invincibility as his predecessors or any of the other current UFC titleholders. Middleweights are desperate to challenge him because they reckon they will defeat him. Romero, Rockhold, Weidman and Robert Whittaker, the man next in line, ride the same wavelength. They’re all confident of toppling ‘The Count’; some even call his knockout of Rockhold a “fluke”. Gegard Mousasi, meanwhile, got so fed up waiting for his chance to bash up Bisping that he bolted to Bellator.

Of all these middleweights, though, it’s Whittaker who seems to have the right approach. He has a history of sorts with Bisping – they were meant to fight in November 2015 – but refuses to allow himself to be wound up by the Brit, much less embroiled in a slanging match. This was evident when Bisping tried to play the heel following Whittaker’s win over Romero at UFC 213 and the placid Aussie refused to go along with it. His response? Smile. Relax. Let Bisping be Bisping.

Though young in the game, maybe Whittaker, 26, is mature enough to realise hate only clouds judgement and that the key to Bisping’s success, especially of late, is that he has completely owned the idea of being hated and has used it as a tool; a tool to make money, a tool to distract opponents, a tool to win fights. Overlooked and frequently derided, he lets opponents get angry, personal, overconfident, and then surprises them not with a shocking foul-mouthed retort – Bisping has been outspoken since day one – but with an underrated and effective set of skills he has honed over the course of 27 UFC fights and a 13-year professional career.

Being shit-talked by a Brit is one thing, but succumbing to Bisping’s pinpoint striking, his doggedness, his toughness, his stellar takedown defence and his seemingly limitless cardio is, for his poor victims, another thing entirely. Before they realise what is happening, it’s too late; too late to do anything but hate the guy.