When James Mulheron was nineteen years of age, he did what many nineteen-year-olds do. He went to Ibiza, tested the durability of his liver and gut, and partied like it was his profession.

Days into this holiday, however, the sunburnt teenager from South Shields decided to do what few other nineteen-year-olds would have the gumption or funds to do: he stuck around in Ibiza; worked the bars; partied some more; went everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Eight months later, he was still there. Still drinking and eating everything in sight, still partying as if it would lead him somewhere further than a kebab shop and someone’s bedroom floor. Mulheron was having fun – how could he not? – but, eight months deep, he realized it was the kind of fun that lasts for as long as it takes for the sun to come up and the memories of the night before to squeeze his head like a vice. Fun like sunbathing before the sunburn. It was fun of the shallow and short-lived variety. Adolescent fun. Fun with a shelf-life.

The British get an insight into this type of fun on their television screens. It’s an insight gained vicariously through the exploits of bronzed, artificially pumped up, protein-obsessed ‘lads’ who, like Mulheron, originate from the north-east of England, and, unlike Mulheron, have made their name on a reality TV show called Geordie Shore. Aspirational figures to some, the very embodiment of a dumbed-down society to others, they are, to me, no more than a handy reference point when a Geordie heavyweight mentions being in Ibiza for eight months.

“Geordie Shore?” says Mulheron. “You’re joking, aren’t you? I really didn’t look like the guys from Geordie Shore. I was about eighteen stone and sweating at the thought of food. They’re constantly working on their bods, and I was gorging on food. It was mint. I went out there to party, drink and eat, and that’s what I did.”

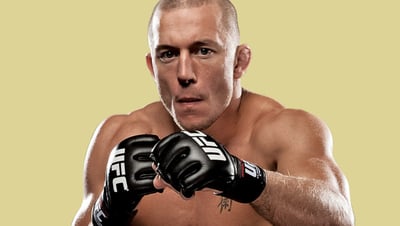

Mulheron may have behaved like your typical nineteen-year-old, but that doesn’t necessarily mean he looked like one. Nor, it should be said, does Mulheron, now an 11-1 heavyweight signed by the UFC, fight the way you’d assume a heavyweight would fight. But Mulheron has long believed looks can be deceiving and that books shouldn’t be judged by covers. He’s self-deprecating like that; as modern males suffer something of an identity crisis, this is how ‘The Juggernaut’, now 29, survives.

“Everyone in the north-east is either an MMA fighter or a tanned, muscled gym-goer, Geordie Shore wannabe,” he explains. “You’ve either got to be a fighter or look like a Greek God. I couldn’t get the Greek God thing going, so I thought I might as well be a fighter.”

Shortly after severing his relationship with Ibiza – the young male’s equivalent of a divorced woman finding herself in India – Mulheron was taken to his local MMA gym by his father. He’d been working menial jobs up to that point and was, he says, driven “demented” by the mind-numbing nature of the work. MMA, though, offered an extreme alternative to the safe confines of a nine-to-five. It was risky. It was dangerous. It wouldn’t pay well, much less offer any kind of stability, yet it was for all these reasons Mulheron was drawn to it. “This is mint, this,” he said, recalling how he was mesmerized by the sight of fighters performing ground moves in the gym. “I thought I might try amateur.”

Mulheron had eight fights as an amateur and won all of them; barely threw a punch, he recalls, so taken was he by the limitless potential of grappling and wrestling. He then turned professional in October 2012. Tentative at first, unsure whether he was good enough, unsure whether MMA could work as a career, Mulheron hung around pros long enough to realize the difference between him and them wasn’t considerable. Confidence followed. Commitment, too.

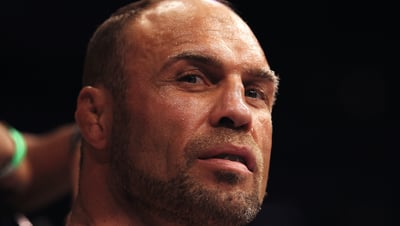

“Just after I turned professional, Phil De Fries, my training partner, was in the UFC and training at Alliance and he invited me over,” recalls James. “I trained with them and watched him fight at the MGM Grand and I came back and thought to myself, well, if Phil can do it, maybe I can do it. I didn’t feel too out of my depth. I thought I’d give it a blast.

“The thing is, I was still working at the time. I was with my partner, Melissa, and we couldn’t really afford for me to carry on with MMA. But I quit my job and moved in with a friend and she moved in with a friend as well. She stuck with me all the way through this. We’ve been together for nearly ten years now and she’s stuck with me through all the hard times and the times when we’ve had no money. She’s helped me through tough times and believed in me when I probably didn’t believe in myself. I’ve been fighting for a pittance at times and it’s been a bit of a nightmare. Now it’s starting to pay off.”

He mentions Melissa over and over again in a yo-Adrian-couldn’t-have-done-it-without-you kind of way. More than throwaway words, or an attempt to sweet-talk his girlfriend, Mulheron speaks with the sincerity of a man who knows he’d still be dry-lining walls if it wasn’t for his tight support network, central to which is his partner. He knows he wouldn’t have a fraction of the self-belief or motivation were it not for them. He knows the UFC would have remained a pipe dream.

“I was doing hard graft and thinking, I cannot do this; surely, God, this is not what life has in store for me,” he said. “I worked at the Olympic Village and helped build the media center there, but didn’t enjoy it one bit. It was driving me mad.

“Luckily, at the time, when I decided to quit, I had people around me who had seen me fight and they were happy to sponsor me. That took away a lot of the worry. I didn’t have to worry so much about bills and stuff like that. I’ve been blessed in that way. I’ve had a lot of people around me who have wanted me to chase my dream.”

Back to the image. Mulheron, in the early days, was deemed a short, overweight slugger with little in the way of reach, discipline or ability. Indeed, he’s the first to admit this. But he also speaks with pride when detailing how he swiftly changed this misconception and how he has found a certain comfort in being one of life’s perennial underdogs.

“I get underestimated less in the UK now, but, at the beginning, everyone was like, ‘Who is this little Jimmy Krankie coming out blasting and as fast as lightning? He’s short and dumpy but he’s quite good.’ As I went through the ranks, they were saying, ‘Oh, he’s doing all right at this level, but what happens when he comes up against better fighters? If he manages to beat them, people will start taking him seriously.’ I beat them and they started taking me seriously.

“Look, I’m not your typical big heavyweight. I’m not six-foot-five. I’m kind of short and stumpy. I’m always going to be the underdog, the person who makes people say, ‘Who the hell is this?’ But I like it when people judge me because I always give them a shock when I show them what skills I have. My style is very unorthodox. I’m so fit. If you try and teach another heavyweight the way I go on, it wouldn’t work. I’ve got quite a unique style. Fast hands. My movement is ridiculous for a heavyweight.”

The heavyweight with ridiculous movement has so far won eleven of twelve pro-MMA fights. His sole defeat, a loss to Ruben Wolf in February 2015, couldn’t halt his movement, nor shatter his confidence. Instead, it merely delivered a reality check at a time he probably needed one. It made him re-sharpen his focus. It made him want it more. It also led to months of rehab due to a broken fibula. Only the pain of defeat hurt more than that.

“When I first fought Ruben Wolf, I was already thinking about what was next,” Mulheron said. “I don’t know if I hit a bit of a wall or didn’t train as hard as I usually did, but he beat me in the first fight. I was winning the fight until we got to the third round. I got caught and then slipped on the floor. My foot twisted and I broke my fibula as I fell. The referee had to stop it.

“After that, I had to do a lot of soul-searching and look at what more I could have done. I’m in the house thinking, do I really want to do this now? Do I really want to fight and put my family through this? But then, ten months later, I was fighting again; I broke my leg in the February and was fighting in November.

“Two years later, I fought Ruben Wolf for a second time. I thought to myself, I’d rather die than get beat here. And, although he was a nightmare again, I managed to beat him.”

That was Mulheron’s last fight. Now, with the British scene conquered, he walks around calling himself a UFC heavyweight contender. His first fight for the organization, a three-rounder against American Justin Willis, takes place in Glasgow, Scotland on July 16.

“I feel fantastic,” he says. “Training is going good and I’m on top of the world. I’ve been working my way through the MMA rankings and I’ve finally done it. I’m here now. I’m on the big stage. I’m ready for it.

“After my sixth pro fight, I fought the established number two guy in the UK (Neil Wain) and everyone was talking about me going to the UFC. I thought then I might get a call. Obviously, I didn’t, but, in a way, it has worked in my favor. I’m 11-1 now and I’ve lost a fight and had to come back from adversity. I’ve beaten the guy who beat me. I’ve had to come back from a loss, a broken leg, and a real low point and be positive and move on. The time is right now. I’ve always thought I should be there and always knew I would get there. It was just a matter of time.

“The last four or five fights have been quite fragile for me. I’ve been thinking, I’ve got to win this, I can’t afford to lose. I put a lot of pressure on myself and was a bit more conservative as a result of that. I didn’t go all out for the win.

“Now I’m there, though, I’ve finally got the buzz back. I’m ready to just explode. I’m the underdog, nobody is expecting much from me, and I can’t wait. I can enjoy my fights again. I don’t have to think, if I don’t win this, I won’t ever get to the UFC; I’ll probably have to retire if I lose this; I’ll lose sponsors and all sorts. Now that has all gone and I feel free.”

Free like a bird would be the go-to line here. But James Mulheron is bucking trends, confounding stereotypes and doing away with cliches. Birds aren’t free in his world. They are cooked, put on a plate and devoured as part of a meal.

“I think I should be really skinny, like a lightweight or something,” he says. “But I like my food too much. I eat everything. Anything delicious. Chinese food, Mexican food… eating is one of the best things in life, isn’t it?”

...