Issue 162

December 2017

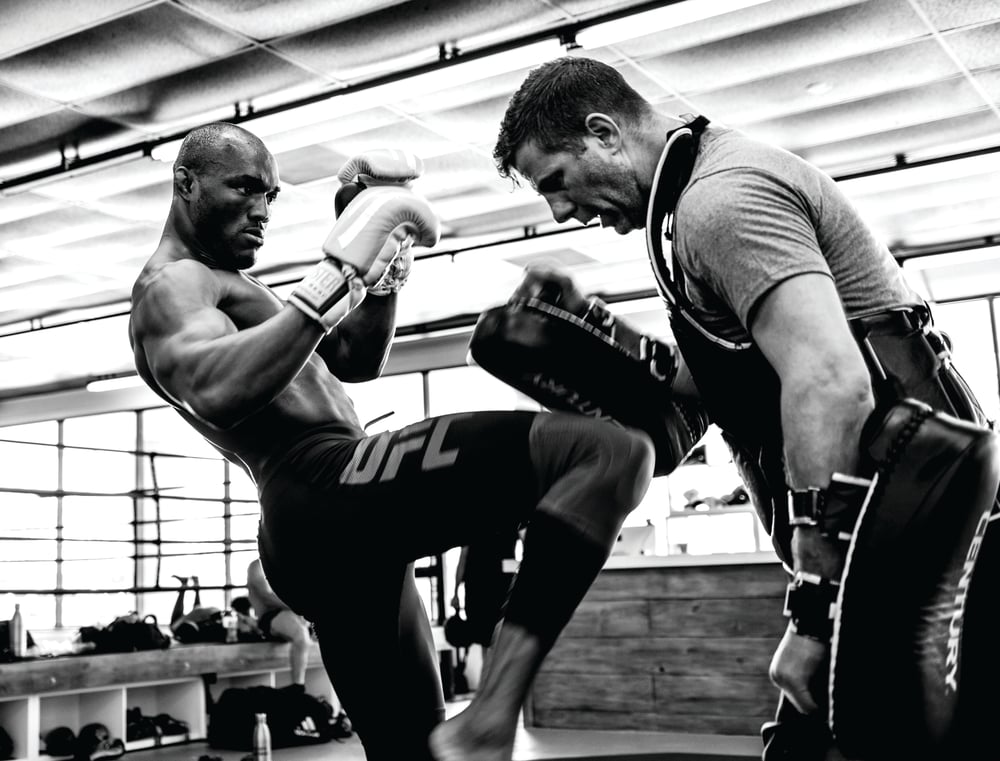

Kamaru Usman is 6-0 in the Octagon and ‘a problem’ for anyone at 170lb. Elliot Worsell discovers how he became a nightmare for UFC welterweights.

Sometimes, life’s defining moments can seem innocuous. In the case of Kamaru Usman, a trip to see his friend, Jon Jones, the future UFC light heavyweight champion, at Iowa Community College during fall break wasn’t, on the face of it, anything more than two freshmen catching up and shooting the breeze. But, unbeknown to either of them, that evening would change everything.

For Usman, a wrestler, watching Randy Couture in a pay-per-view main event that night was his introduction to MMA. He’d heard about it, but never before seen it. He knew fellow wrestlers were gravitating towards it and he knew Jones, the bigger wrestler by his side, had already toyed with the idea.

The night’s host, meanwhile, a mutual friend and the Golden Gloves boxer, could see what the future held – for both of them. To him, it was obvious. “Hey, you guys should do this,” the friend said, referring to the MMA fight on screen.

Jones and Usman exchanged a sideways glance.

“Erm, no, I don’t think so,” they agreed. Committed to the idea of hanging Olympic gold around his neck, Usman saw no way of relating to what Couture was doing inside the Octagon.

“The thing is, after I was done chasing the Olympic dream, MMA was the next step for me in terms of testing myself,” Usman, now a top-15 welterweight with designs on becoming champion, tells.

“I knew I wanted to compete and be the best in the world at something. When I left the Olympic training center, I was going to switch to boxing because my girlfriend was a boxer on the Olympic team. But then I realized that would mean four years of having to learn it and go through the amateur system. Also, I would completely neglect the skill I had spent almost 10 years trying to perfect. So I decided MMA was the next option for me.”

He makes it sound preordained. But the truth is that Usman, now a thoroughbred athlete, was 5'2" and “103lb dripping wet” in ninth grade. He was once tackled so hard during football practice he questioned everything: how to avoid it happening again; how to avoid football practice; how to avoid pain; his future.

“Our assistant football coach happened to also be the assistant wrestling coach and he asked if I wanted to try wrestling,” he explains. “But the only wrestling I’d ever heard of was the WWE stuff, so I said, ‘No, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to get hit with a chair.’ He laughed at me and said, ‘Why don’t you just come in and try?’ So I did. After the football season, I went to one practice and got my butt kicked really bad by this girl.”

‘This girl’ was Angela Martinez, a three-time state champion, and Usman, unaware of her pedigree at the time, couldn’t fathom how she’d been able to humiliate him in what he perceived to be a boy’s world. He promised revenge the next day. He convinced himself it would be different.

Only it wasn’t. His butt was kicked for a second and third time. Three weeks later, Usman was still there, still trying, still getting chucked around by a girl.

“One day I hit her with this one move, this head-lock, straight to her back, and I’m holding her down, pinning her to the mat, and I look at my coaches in excitement,” he remembers. “I was like, yes! I picked up something. I couldn’t turn back after that.”

What Usman lacked in stature he made up for with steely determination and a desire to make something of himself. Born and raised in Auchi, Nigeria, he spent the first seven years of his life in West Africa, before being moved to Arlington, Texas, by his pharmacist father. He believes these formative years shaped his personality, values and his approach to athletic competition.

In sport, as in life, he’s both hard-headed and level-headed. He listens. He wants to improve. He wants a brighter future. And he appreciates what he has got.

“My mom can’t believe I remember so much about it, but it’s like a vivid picture painted in the back of my mind,” Kamaru says when asked about life in his homeland. “We didn’t have much. We had a farm with goats and chickens. We knew what we had to do every day and we got it done.

“Over here (in America) it’s all about how much money you can make, how many cars you’ve got, how many things you can acquire. Over there it wasn’t like that. You just want enough to allow you to survive and be happy. You appreciate the simple things.”

Fighting, for the Usmans, was never really the plan. Kamaru’s older brother decided to become a pharmacist, while his younger sister is currently at nursing school. Another brother, Mohammed, started out playing football, but has, like Kamaru, found his way to mixed martial arts. Unlike Kamaru, however, he’s a 6'1", 260lb heavyweight known as ‘The Motor’.

“I think it’s an immigrant thing to seek a better life,” Usman says. “They push their kids towards careers that are secure, which is why you see a lot of immigrants who are doctors. There is a lot of demand for that.”

By the time Usman turned 25 and his Olympic dreams had fallen by the wayside, he was short on options. Tempting though it was to follow siblings towards a stable career, he knew that aborting mid-mission would mean a lot of good stuff – genes, talent, years of wrestling experience – going to waste.

With some persuasion from former UFC 205lb champion, Rashad Evans, he finally turned to mixed martial arts, though the transition was far from straightforward.

“It took a while,” he says. “You can learn how to throw punches in a fairly short time, but learning the balance and intricacies of how to block and evade a punch and be able to counter and be OK with the punches coming at you is something that takes a lot longer. That is something I am still getting used to today. It doesn’t matter what shape you’re in, or how well-conditioned you are: if you’re not able to relax under pressure with punches coming at you, you’re done within a minute. You will feel like you didn’t even train.”

Now 29, ‘The Nigerian Nightmare’ speaks from experience. He knows how it feels to walk away victorious and to also wallow in defeat. It’s the latter, of course, that usually serves up the greatest lessons and provides the incentive to get better. Usman, defeated in only his second pro fight, knows this is true.

“I knew I could take anyone down and control them on the ground, but the problem was I wasn’t training jiu-jitsu,” he admits. “I didn’t feel I really needed that. I knew I had to work on my striking, so I was taking that seriously, but the jiu-jitsu and ground game I didn’t take seriously. I took the fight on a week’s notice. I needed money. I was broke.

“I went into the fight, took him (Jose Caceres) down within 15 seconds and full-mounted him. I started raining punches down and then decided to throw elbows. As I’m throwing elbows, this guy, who was about 6'2" and really flexible, throws his legs around my waist while I’m in a full mount and knocks me backward. It was something I had never seen before.

“Next thing you know, I panic – what’s going on here? – and try to get off of him. He climbed on my back, sunk in a rear naked choke, and all I could think was, wow, this is happening. I’m about to lose. It was a feeling I hadn’t felt in a long time. I’d been winning national championships and wrestling at the Olympic training center for years. It had been a while since I’d felt defeat on a stage like that.

“I sulked all week. I was in my room and didn’t want to come out. I felt like everybody in the world hated me. I was staying with Rashad Evans and he was trying to get me out of the room to go and do something. After about a week, I said to myself, why did that happen? What am I lacking? I knew I needed to train everything and put everything into the sport.”

He did. He’s still putting everything into it. It’s the mentality that led him to a spot on The Ultimate Fighter, despite claiming he’d never appear on the show after a coaching stint on season 14.

It’s what won him the TUF 21 crown. Now, it’s what powers an unbeaten run that has reached 10 fights, punctuated by a stunning first-round knockout of Sérgio Moraes that proved he’s not just a powerhouse wrestler who grinds out wins over 15 minutes. He’s “a problem” for anyone at 170lb wherever the fight goes.

“I came into this sport as a full-blown wrestler and I know that is something I can always fall back on,” he says when pressed about the decision wins. “I can take someone down and hold them down.

“I’d only been doing the sport for three years before getting to the UFC. I was still learning the intricacies of the stand-up and how to throw punches the correct way. I finished The Ultimate Fighter and had pretty severe knee surgery that would normally take eight-10 months to recover from. But I had to fight in three months.

“When you have something like that, and it hinders you in a major way, you’re going to go to what you know can win fights. I went to my wrestling because that’s where I was comfortable and because I was still working on my striking. There’s also the fear of losing again. If you lose in the UFC, they can give you that ax. There’s a lot at stake.”

So Kamaru Usman and Jon Jones, friends and wrestlers, ended up doing the thing they said they would probably never do. For one of them, Jones, success and the spotlight came quickly. For the other, Usman, the journey figures to be slower, quieter. And he’s just fine with that.

“Our coaches (at Blackzilians) preach to us we should work in silence,” says Kamaru. “They say people run their mouth when they know their skills are not up to scratch and then get exposed. I worked in silence and wanted to develop my skills. I don’t want to be ignorant and say things I can’t do. I want to be able to say things, then go out and prove it.

“The way the UFC is going right now, it’s more of an entertainment thing. Guys basically want to be movie stars. They say all these outlandish things because that’s our society now. People don’t pay attention to you unless you’re the crazy guy. But I’m not going to sell my soul for any of that. I’m going to stake my claim and let you know what I’m capable of doing, but I am not going to tarnish my name. I think my actions will prove I’m the best welterweight in the world.”

His actions inside the Octagon have so far been exemplary. The volume, too, is starting to increase. He has called out Rafael dos Anjos, Mike Perry, and Neil Magny. He even predicts he’ll stop Tyron Woodley in three rounds next July to become UFC welterweight champion.

“Much respect to the champ – he’s champ for a reason and he packs a lot of power in his punches – but I just don’t think he’s really been working in those areas like I have,” Usman says. “He hasn’t had to dig deep in a long time, or rely on grappling, or been in fights where you’ve had to go until you can’t go anymore.

“He hasn’t been pushed. I think that’s a way I would be able to get at him. That’s what I bring to the table. That’s what I bring to every guy, and that’s why they want to get around me. You fight me and the only thought in your head is, ‘How can I survive?’ You don’t think about winning, you think about surviving.”

Slowly but surely, Kamaru Usman, the 170lb quiet man, is starting to make some noise.

Worst nightmares

Kamaru Usman goes by the nickname ‘The Nigerian Nightmare’. He accepts that there’s nothing original about his nom de guerre, but that’s the reason why he likes it. It’s been used by many before him, represents lineage and history and works as a tribute to those Nigerian sportsmen who walked a similar path.

“The name has significance,” he explains. “It represents a Nigerian athlete who is excelling in his sport at the highest level. Christian Okoye was a football player for the Kansas City Chiefs and one of the better-known Nigerians in America. He was ‘The Nigerian Nightmare’.

“Then Samuel Peter came up and was one of the biggest names in combat sports. After he left boxing, I knew ‘The Nigerian Nightmare’ was the name I looked up to and identified with. I see it as my time to pay it forward and carry on the legacy of that name.”

...