Issue 209

September 2024

October 21, 2004

Atlantic City, New Jersey

UFC 50

By Brad Wharton

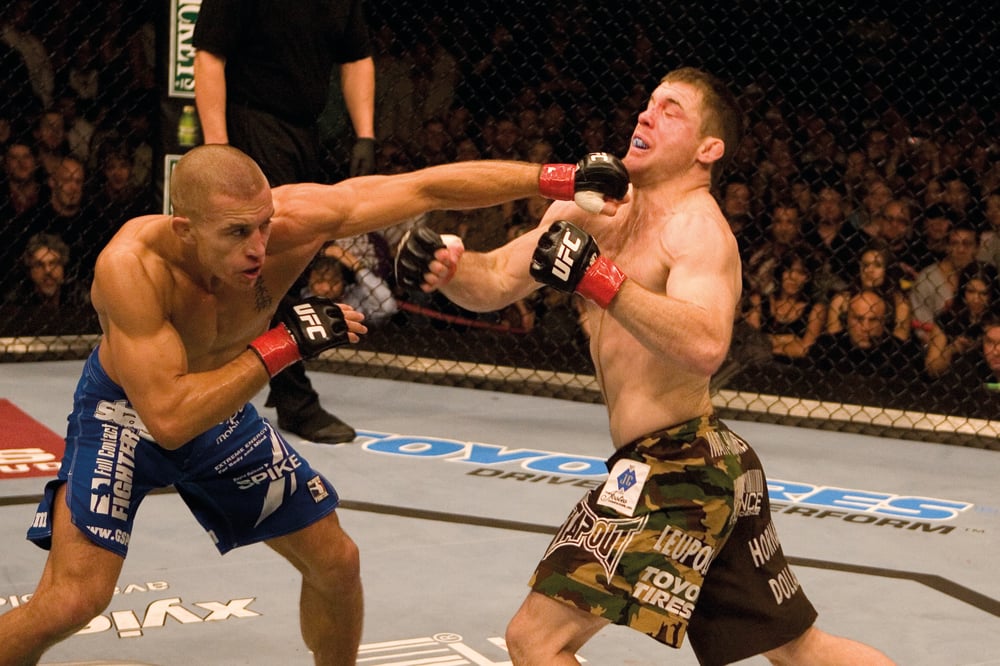

UFC 50 was supposed to be the final chapter in one of the promotion’s earliest three-part rivalries. Fate had other plans. Instead of a conclusion to the Guy Mezger/Tito Ortiz trilogy, we were graced with the genesis of a guard-changing feud for the ages. Matt Hughes was an institution as the UFC’s welterweight kingpin. He was the workhorse champion of the early 00s who cut an understated figure in stark contrast to the brash, outspoken Tito Ortiz. As a result, a somewhat puzzling fight was made, which saw a forty-bout veteran, Hughes, face relative UFC newbie and seven-bout novice Georges St Pierre, with the vacant welterweight title on the line. On the surface, it looked like a surefire way to get the strap back on Hughes.

It was legend versus rookie, proven commodity versus future potential, promotional mainstay versus flavour of the month. And besides, a defeat to Hughes at such an early stage in his career would hardly derail the potential of the French-Canadian upstart. But to those ‘in the know’, the conversation went deeper. St Pierre, untested as he was, genuinely looked like he could represent the greatest evolution of MMA fighters since the Gracies started punching. On the other hand, Hughes was nothing if not a safe bet. Recapturing the 170lb title would reaffirm the status quo, or he’d pass the torch and anoint a new welterweight king. Either way, in the shadow of a makeshift main event, the future roadmap of one of the UFC’s most important divisions was about to be sketched out.

A COUNTRY BOY CAN SURVIVE

Matt Hughes was never quite the star he should have been, and his appearance at UFC 50 was symbolic of that. Even in the face of Guy Mezger being hastily replaced in the main event by 5-0 prelim fighter Patrick Côté, his bid to become a two-time UFC champion was relegated to halfway through the main card. Only two of his six previous UFC title fights had received headline billing.

There were no flaming shorts, dyed hair, or stream-of-consciousness trash-talk marathons from the Iowan. He walked to the cage to the tune of Hank Williams Jr’s ‘A Country Boy Can Survive.’ This was an anthem for “them old boys raised on shotguns,” who weren’t about to change just because the times were.

Hughes was country-strong - a beneficiary of nature’s strength and conditioning regimen. Born and raised on the family farm and with a D-1 wrestling background, Hughes’ ability to hoist anyone he got his steel cable grip around and drive them into the mat was the stuff of legend. Everybody knew it was coming, but nobody could stop it. The times did seem to be changing, though. Hughes had lost his belt in shocking fashion, getting hooked by lightweight phenom BJ Penn in the opening round of their UFC 46 clash. With Penn out of the door following an ugly contract dispute, the UFC was looking to a northern star as their welterweight heir apparent.

RUSH HOUR

The UFC had welcomed plenty of high-level athletes through the Octagon gates over the years, but something about the 22-year-old who’d rocked up to the UFC 46 prelims and rolled through favourite Karo Parisyan seemed a little different. Georges St Pierre looked like the kind of elite who could have excelled at any sport he’d chosen. It just so happened that he had the mind and soul of a martial artist. Hughes was straight back in the mix at UFC 48 in a curtain twitcher against Jay Hieron that ended after 82 seconds of clinical violence. He looked the part, walked the walk, and after two appearances on Matt Hughes’ undercards, the UFC was about to go all in on ‘Rush’ as the man to face him for the vacant welterweight title. Everything about it screamed ‘too much, too soon’ …but was it?

THE WAR OF 04

Just minutes after former Hughes opponents Frank Trigg and Renato Verissimo had battled it out in a de-facto #1 contender bout, the former champion took to the cage opposite St Pierre. “I’m not scared…” GSP had insisted during the pre-fight as if to dispel the notion that this was some kind of ‘man versus boy’ affair. Actions speak louder than words, though, and as the bell rang, St Pierre did the unthinkable. After finding his range with a crisp jab, the young upstart blasted Hughes with a takedown, snatching his right leg and driving him to the canvas in the centre of the cage. GSP’s time spent training with the Canadian Olympic team may have paid off with the takedown, but Hughes was already busy working on a guillotine and obtaining guard.

It wasn’t a position fans were used to seeing from Hughes – or any elite wrestlers of the time. However, analyst Eddie Bravo rejected commentator Mike Goldberg’s view that it was a bad spot for the former champion. Hughes was nothing if not an exceptional submission grappler, BJJ grading or not. As if on cue, Hughes wrestled back to his feet but couldn’t complete the subsequent takedown. The pair traded jabs, but it quickly became clear that St Pierre had a more effective arsenal on the feet than Hughes’ ‘meat and potato’ boxing.

The American eventually managed to drive his man onto the cage and, after a couple of failed entries, went back to his bread and butter, elevating St Pierre skywards and driving him down into the mat. Hughes was a veteran of the collegiate mats, but St Pierre had learned wrestling for MMA. After attacking a kimura on one side, he kicked off the cage on the other and got back to his knees, overhooking the left arm and returning to his feet. As the pair separated, it quickly became apparent that nobody was out of their depth. A spinning back kick landed for GSP, and Hughes looked immediately troubled, backing off and resetting before shooting a sloppy double that barely warranted defending. A relentless Hughes scored a second takedown with just over a minute left in the round, slipping straight into side control to separate his man from the cage. Drawing St Piere into the centre of the cage, Hughes again went to the side and teased passing to mount. As his opponent bit, he switched direction and went anticlockwise around St Pierre’s torso, snapping on an armbar that had him tapping quicker than Fred Astaire.

THE AFTERMATH

Despite his pre-fight protestations that the moment wasn’t getting to him, GSP would later admit to being terrified fighting Hughes, who he considered an idol and inspiration. It had been visible on the young man’s face during the final instructions; St Pierre hadn’t been able to meet Hughes’ gaze, and cornerman David Loiseau had to seemingly snap him out of it. Hughes would defend the title twice during his second reign while facing Royce Gracie in an inter-generational super fight that broke the promotion’s PPV record. St Pierre would get another crack of the whip three years later, demolishing Hughes to capture the UFC’s 170lb title for the first time. Thirteen months later, the pair would meet for a final time, with GSP submitting Hughes via armbar in the dying seconds of the second round to bring one of the UFC’s great sporting rivalries to a full-circle conclusion.