Issue 192

September 2020

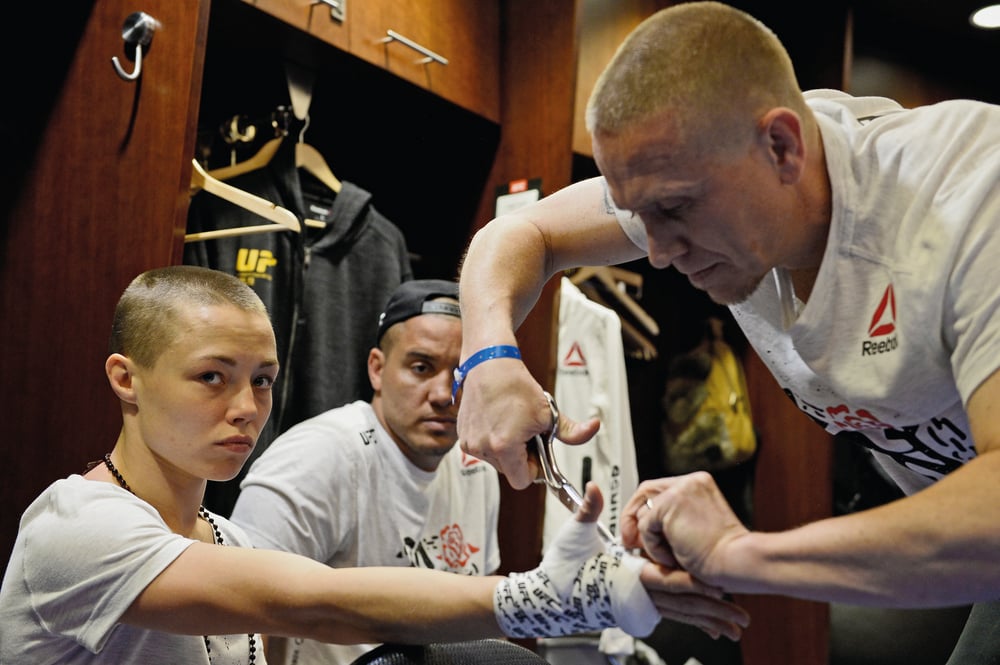

Coach Trevor Wittman is famous for a smile that reflects his upbeat outlook on life. Now with the likes of Justin Gaethje and Rose Namajunas in his charge, he’s getting some deserved recognition and has plenty to smile about.

For a long time Trevor Wittman was known as much for his bright smile and positive outlook on life as he was for being one of the standout coaches in mixed martial arts.

Seemingly always upbeat and cheerful, Wittman has for years been the beaming, expressive face you see resting on top of the Octagon fence before fights, clapping his hands and motivating his fighter, as well as the similarly animated face you see in the corner between rounds offering instruction to his fighter as though all will be all right in the end.

More than just a smile, what Wittman brings to the likes of Justin Gaethje and Rose Namajunas, to name just a couple of the fighters he has coached, is an attitude, a simplicity and an energy, all of it infectious. He smiles because he loves what he does for a living and because nothing excites him quite like the process of guiding a fighter for whom he cares into a fight. It is a smile present both in victory and in defeat but a smile perhaps never as wide or as bright as it is right now.

Why? Because at last the wider MMA world is starting to realize what ardent followers of the sport have known for years: Trevor Wittman is, at 45 years of age, one of the very best coaches the game has ever seen.

“Overcoming obstacles and facing your fears, that is the key to life and the key to winning championships,” Wittman told Fighters Only. “One round at a time, one day at a time. Focus on being the best today and focus on being the best in this round. There’s a lot of simplicity that go together with fighting and life. I definitely look at myself as a life coach as well as an MMA coach.”

Be that as it may, long before becoming either of those things – life coach or MMA coach – Wittman cut his coaching teeth in boxing, having initially turned to that sport in the hope of one day competing professionally. It was there, in boxing, he developed both a love for combat sports and also a student’s eye, something he would later put to good use.

“It was my passion and my dream,” he said of boxing. “When I moved to Connecticut, my friend, Adam Surfer, was boxing. I went to the gym and he was very talented. I got into it. From a professional standpoint, I loved Ike Quartey. He had a unique style and an amazing jab.”

Born in Denver, Colorado, Wittman’s graduation from student to teacher had as much to do with fate as any constructed plan. At 19, for instance, while in the throes of a fledgling amateur career, he was struck down by a lung issue which both curtailed any hope he had of competing professionally and inadvertently acted as the catalyst for something else.

“My son’s mother, Katie, had come to drop my son off and she said I didn’t look right,” he recalled. “I just thought I had the flu or something. I had no energy. I was working for a Danish company delivering Danish food in the morning and would train after that. I ended up going to see what was going on.

“The nurse checked my pulse, I received a shot of adrenaline, and that’s pretty much how I found out I was injured. I thought I could train through it. It was a freak accident. I went to see two different doctors. One told me I shouldn’t box anymore, so I went to someone else and they pretty much said the same thing.

“It was heart-breaking because boxing’s what I wanted to do. I had all these side jobs but that’s what I wanted to do. I’d had an entire amateur career as well. It was a very tough time for me.”

Trevor Wittman will never know how good he could have been as a professional boxer because the opportunity was never his to take. Instead, he had to follow the advice of doctors and cut short a promising amateur career before it had really taken off.

Interestingly, though, it was only once he started thinking about the sport from the perspective of a coach rather than a fighter that Wittman’s grasp of both boxing and his own potential became clearer. In switching perspective, he could now see where he had gone wrong in his own career and, more importantly, see all the ways he could help other fighters not make the same mistakes in theirs.

“Once I started coaching, I knew how much I could help people,” he said. “Do I think I would ever have been great? I don’t know. I wouldn’t call myself lazy, but I didn’t have much direction. I was just boxing because I enjoyed fighting. When it came to doing long runs and other stuff, I didn’t love that part. I loved training and hitting bags, sparring and the competition. But when it came to the real work, I didn’t do much of that. I don’t think I would have been the best. I was at the age where I knew (as a coach) I needed to stay on top of my guys.”

Though Wittman was more an unsung hero than a renowned coach during his time in boxing, he did some noteworthy work with the likes of IBF and WBO junior-middleweight champion Verno Phillips, junior-middleweight contender JC Candelo, and WBO light-heavyweight title challenger DeAndrey Abron. Often living with these boxers during training camps, Wittman would adopt a hands-on approach to his role as head trainer, placing as much emphasis on training his fighters’ minds as he did their bodies, and experiencing the process with them every step of the way.

Case in point: the night Verno Phillips faced Ike Quartey, a hero of Wittman’s, in June 2005, Wittman was living vicariously through his fighter and wearing many hats. First and foremost Phillips’ coach, he was also having to wrestle that night with the fact his own boxing story had come full circle and that the man he had grown up idolizing was now opposing one of the men he had come to train.

“That was one of the coolest fights I ever got to experience,” Wittman said. “Seeing him (Phillips) in there with a guy who was my favorite fighter growing up was very unique. I was very excited about that fight.

“We dropped him twice in the ninth round, but they only called one. The second one the ref called a slip, which clearly it wasn’t. That (had it been called a knockdown) would have got us the win.

“Ike Quartey was very cool. I idolized him and it was very cool to go out and compete against him from a coaching standpoint. He was one of the humblest guys I’ve ever met.”

In the end, the Phillips journey would be the apex as far as Wittman’s boxing story would go. And yet, when later finding his way into MMA, Wittman would do so initially in the role of a standalone boxing coach, someone typically brought on board to help fighters sharpen up their punching ahead of fights against opponents eager for a stand-up battle.

“I started with Duane Ludwig,” Wittman said. “He reached out and said they were fighting a very good boxer and needed me. The fight fell through and then Duane had a kickboxing match and I experienced that for the first time as a coach.

“About three months later we got to fight Jens Pulver and Duane stopped him with a shot we were drilling: the right hand. Nate Marquardt came to me after that and led me to a lot of other guys.”

Any trepidation Wittman may have felt in moving from boxing to MMA fell away quickly and soon it had replaced the previous love of his life. Looking back, this should have perhaps come as no surprise.

“I started in karate before I got into boxing because I wanted to be a ninja as a child,” Trevor explained, admitting it was likely Mike Tyson and his run of knockout wins was the trigger for him later making the switch to boxing. “I wanted my parents to send me to Japan. I fell in love with all the ninja movies.

“When I got to go with Duane to Japan and corner him in K1, I was blown away by it all. It blew my mind how good a lot of these kickboxers were. I fell in love with it. There was something unique about it, too, because I could train a lot of guys, whereas in boxing I only had three guys. MMA, I could train a group of 30 people.”

Though he had the option of training 30 people had he wanted to, Wittman eventually understood this was not the best way to go about the job. Remembering what got him there in the first place, he would opt for a more hands-on approach and found his greatest moments of success as a result.

“After doing that for ten years, I realized I was coaching too many,” he said. “I was coaching a team in MMA and when I went back to coaching two or three athletes, I noticed the level of performances and how much they got back from me.

“I will never go back to training a team. I just don’t think that works. You don’t get the coaching benefit. I get to really focus on them.”

Much of Wittman’s coaching philosophy stems not from his own experiences as a boxer but rather the experience he gained from watching other coaches and teachers on the way up.

Indeed, when discussing coaches and teachers in relation to his own style and methods, he won’t necessarily attribute the work of those in combat sports, be it boxing or MMA, as being his primary influences.

In fact, Wittman’s inspiration goes back a lot further than that.

“It was one of my teachers who was the wrestling coach at high school,” said Wittman, who admits he didn’t actually wrestle in high school. “I was always messing around with the wrestlers. I’d come in and challenge the guys in jeans. I was a very skinny kid and I told him I wouldn’t wrestle because I’d have to wear singlets.

“I was in a class for special needs because I had ADHD very bad and he was the teacher of that class. He really changed my life. I was struggling at school and he was very good. He was hard on me, but he’d always tell me when I was doing well. He would challenge me.

“His words made me feel like I could move forward. He was a very important person to me.”

The man’s name was Jim Day. He sadly passed away last year, Wittman revealed, but, before he did, his former student got the opportunity to reconnect with him after so many years and thank him for molding him into the man – and coach – he ended up becoming.

“I reached out to him about ten years ago and thanked him for changing my life,” Wittman said. “He was one of the reasons I changed my life.

“When I reached out to him it was an emotional moment for me and I do believe he was key to making me believe in myself.

“I actually coach off his philosophy. He was positive and he always let me know I was in the fight. He had a really good way of doing that.

“When I was boxing, my coach was very negative and never helped me at all. When you have someone who is a teacher for you, he teaches you to move forward and that it’s okay if you make mistakes. Then I had a boxing coach who would tell me I’d never amount to anything even though I won every fight. He (Day) taught me a coach can be a positive influencer.”

Wittman ability to find the postives in unlikely situations extends to his own attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which he believes was something he used to his advantage – both in terms of his intense focus and obsessive approach to a passion – rather than something he let hold him back.

“One hundred percent,” he said. “When I was younger, I could never attack one task, but I was steps ahead of people when it came to answering questions on math. If I was focused and I loved the subject, no doubt I could work three different perspectives at one time. I do think ADHD can be a positive thing.

“Justin Gaethje was very similar to me when I was growing up. I talk to his family and see the people he grew up with and they say he was so crazy when he was young. When I see him have his hyper moments it’s very intriguing to me.

“Justin is unique, but he’s also very similar to me when it comes to attaching to people. He’s very intelligent on a whole different level.

“I really like to bring the best out of people. I think that’s where the ADHD is helping me just watch, learn and study them. I think there’s uniqueness in everyone. I really try to attach on to what is special in people. You might not be good at everything, but what is the thing you really obsess over?

“A lot of times we get away from what’s purposeful to us. The seriousness of life takes over. I always say if it’s a hobby, you can be great at it in some industry and make it a labor of love. That’s what I do as a coach: find out what makes them burn and what makes them get up in the morning with excitement.”

Luckily for Wittman, he found his purpose. Now, as well as training the likes of Gaethje and Namajunas, he runs a private gym and an equipment company, ONX Sports, he decided to launch when his body started breaking down under the weight of heavyweight punches. Keen to make better equipment, with a greater emphasis on protecting the bones and joints of fighters and coaches alike, Wittman now spends as much of his time designing gloves and pads as he does lacing or holding them.

“I learned how to make my own mitts and sew with my mom’s sewing machine,” he said. “That’s my art, my technique. I teach in fights. I look at it from an art standpoint: balance and fluidity. Art is in my life. Without art, creativity and creation I would be lonely.

“(Pablo) Picasso always knew what he was going to paint. He would tell people, but they couldn’t see it until he put it on a canvas. That’s like me. I tell my wife about what I’ll do with my next glove, and she has no idea what I’m talking about. It’s not until it’s real that you can see it. It’s fun to take something from my mind and make it real. You have to have a dream before you can make it reality.”

When finally a vision comes to life and a dream becomes a reality, you can afford yourself a smile. When, on top of that, some long overdue respect comes along with it, you may even smile like Trevor Wittman.

...