Issue 063

June 2010

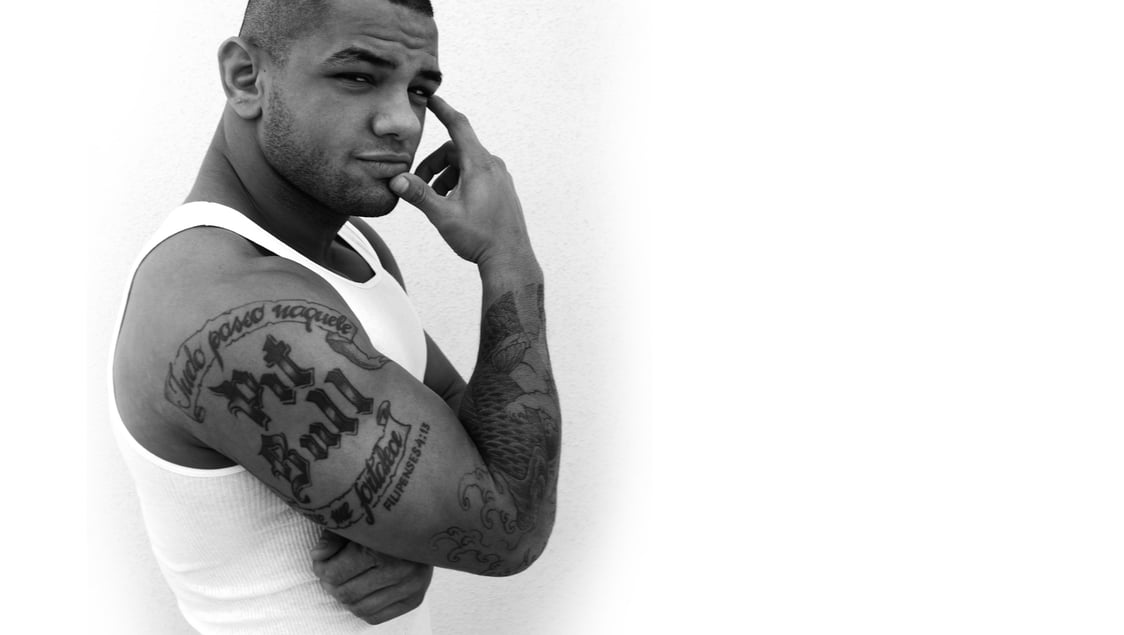

The stringent safety tests and procedures in place in the Ultimate Fighting Championship saved the mixed martial arts career of welterweight Thiago Alves. We reveal that the discovery could also have saved his life.

In the week preceding UFC 111, a computed tomography [CT] scan had revealed an irregularity in an artery in Alves’ brain. He was withdrawn from his contest with Jon Fitch – Alves was in pieces. Fans feared the worst.

Less than 48 hours later, Alves learned that he would need a surgical procedure that, once successful, would mean he could fight again. But behind the scenes, the condition was actually more complex. According to one of the world’s leading neurosurgeons, ten years ago his career would have been over. Thirty years ago, the condition would have stayed undiscovered, and he may have suffered a stroke, or may even have had a brain hemorrhage.

Alves underwent an eight-hour operation to separate an artery from a vein in his brain on Wednesday, March 31. He was then in the intensive care unit at St Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York City, for the following two days, under the care of specialist Dr Alejandro Berenstein, a neurointerventionalist.

The CT tests had showed "absolutely no bleeding or swelling" in the brain, but doctors located a problem with an artery and decided to err on the side of caution, his agent Malki Kawa explained. Understandably, Alves had been desperate to fight. He had been nursing a knee injury and had not fought since unsuccessfully challenging incumbent champion Georges St Pierre for the UFC welterweight title in July 2009 at UFC 100.

The head-to-head with Fitch, highly anticipated by fans, was a rematch of their 2006 Ultimate Fight Night battle, which Fitch won by TKO in the second round. Alves was gnawing for revenge.

Alves is a religious man – he prays often. Yet for him and his well-being, the combination of advancements in medical science and the due diligence of those who officiate the sport saved his career, and potentially, his life. God really was on his side.

According to one eminent neurosurgeon based in the UK, the abnormality discovered and queried in Alves’ head found prior to UFC 111 in New Jersey was doubly fortunate for the Brazilian: It was both treatable and once dealt with made his return to the sport possible. Had it not been spotted and treated it may have presented a substantial risk to his life as he grew older.

The advancement of testing procedures in MMA should be both applauded and pressed to the limit. There has never been a death or serious injury in the UFC since it began in 1993. Contact sports carry inherent risks; the case of Thiago Alves is a reminder that in spite of the nickname ‘The Pitbull’, all creatures – great and small – have vulnerabilities and frailties. Man remains mortal, yet testing procedures save lives.

As the Brazilian prepared himself to battle for a second time with Fitch in Newark, New Jersey, he was suddenly faced by a medical stipulation dictating that his license had been revoked. His mind went into overdrive. For 48 hours he was left asking more questions than he had answers.

Thanks to the insistence and due diligence from the likes of Nick Lembo, head of the New Jersey Athletic Control Board, Alves was (rightly) pulled out of his contest, and even though he had minor surgery there could have been major repercussions. The issue was not blown out of proportion but was serious in itself. Moreover, Dana White, the UFC president, and Zuffa co-owner Lorenzo Fertitta acted with alacrity and called on one of the leading specialists in the US to deal with Alves’ malformation in his brain. Within a week of discovering the abnormality, Alves awoke in a ward in a New York hospital, effectively with a second lease of life.

Peter Hamlyn, honorary consultant neurosurgeon at University College Hospital, London (the man who saved former boxer Michael Watson’s life with six painstaking brain operations back in 1991, and who has operated on many injured sportsmen), explained how medical advancements have enabled patients who have an arterial venous fistula – Alves’ malformation – to continue their careers in sport.

“The malformation connects a high-pressure artery to a low-pressure vein, which gets stretched over time and which can eventually burst, which would cause a brain hemorrhage,” said Hamlyn. “When I began as a brain surgeon many years ago, we had to make an opening in the skull and repair it. At the time, it meant the end of a career for many sportsmen, such as fighters, jockeys and rugby players.

“Ten years ago, given that condition, the career of the fighter concerned would have been over. Diagnosis was not possible 20 or 30 years ago, but this treatment has been developed in the last ten years. Now these operations can be done from the groin, with fine catheters inserted inside the arterial system. These are guided up into the arteries within the head where a form of ‘superglue’ is used to block the offending artery, or fistula,” he explained.

“The tiny catheter is passed up through the artery, into the abnormality, and the flow of blood drags the ‘superglue’ where you want it to go. It is guided or steered by a very fine wire. The operation can take an hour or many hours. If someone has this malformation and the organ concerned is his brain, it is all the more important that it is operated on – this is the kind of malformation which can be the cause of stroke in young people if it is not treated.”

Talking of a case such as that of Alves, Hamlyn explained: “A sportsman in such a situation is lucky in more ways than one. The fact that this was a fistula means that, properly treated, a return to contact sport is possible. Yet if it had not been treated, he would not have been safe to play in his sport, and at the same time would have faced a substantial risk to his life.” Alves can count himself very lucky, then.

Nor are such measures a precedent in UFC events – safety concerns are never far from the surface. In the days leading up to UFC 72 in Belfast, concerns over another fighter were unfolding, far from the eyes of journalists. There was a question mark hanging over Dustin Hazelett, the American jiu-jitsu expert.

Doctors had been concerned with the results of the young welterweight's CT scan. Hazelett was scheduled to fight Ulsterman Steve Lynch; his withdrawal meant potentially leaving the UFC short of an opponent for a hometown hero fighting at an event staged in Northern Ireland for the first time. The mixed martial arts organization flew in veteran fighter Rich Clementi as a possible replacement for Hazelett while further tests were carried out. Luckily for all concerned, the fears were unfounded – Hazelett was fit to fight.

In the case of Alves, a stringent testing process had thrown up anomalies. Alves recalls the sequence of events: “First of all, I did an MRI and all my medical examinations back in Florida [where he lives and trains], and then I went to New Jersey to do a couple more tests ahead of UFC 111. The last time I went there, to New Jersey, I was required to do tests before I fought Chris Lytle [at UFC 78, November 2007].

“I had the tests done [in Newark], went for a workout and then got back to the hotel. My manager rang me and told me I would not be able to fight at UFC 111. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know what to think. ‘You have got to be kidding me, how can I not be fighting on Saturday night?’ I said to him. He was trying to explain to me what was happening and the procedure, and I couldn’t really understand the details of what was happening very well.

“They compared the MRI scan I had in 2005 with the one I had a couple of weeks ago. They saw a malformation in my head – it could have been something I was born with or developed over the years, and it was too close to the fight to find out about. They did not want to take the chance,” he explains.

“Then the next day I heard – through TMZ [the celebrity news channel] – that it could be career-ending. So I had gone from being ready to kick some ass in the Octagon to thinking I would never fight again. I was numb for two days.”

Over those 48 hours, Alves went to some dark places in his mind. “I was just concerned about what I would do with myself. I have put my life into this business, I have been a professional fighter since the age of 15, and thinking that I may never fight again seemed incredible. I was very low – I saw my career ending. It is something you never want to hear. I have a lot of faith in God, and I didn’t come to the US from Brazil at the age of 19, leaving everyone I love behind, not to accomplish what I set out to do in mixed martial arts. I prayed, and I cried.”

As tough as The Pitbull may be, the news that his career may be over meant he had to draw upon every ounce of his inner strength, but also on the support of his faith. “I’m not really the kind of guy who complains too much, or wonders ‘Why?’ about things. All my life, I have picked myself up and fought on when things don’t go right. I cry, I pray and then I am back up again. Everything happens for a reason – I have a lot of faith in God – and I know that all of this has happened for a reason. In this case, it was 48 hours of a dark place and a lot of praying.”

For two days Alves’ future hung in the balance. That was until he received the news he had been praying for. “It was not until I got together with the doctors and we talked through the issue on Friday night [March 26, the night before UFC 111] that I knew I would have to have an angiogram, through the boxing commission, to find out whether I would be able to fight again – then I found out it could be fixed. But from finding out what was happening at the start, to having the operation felt never-ending.”

Someone who knows the same mental anguish and torture Alves experienced is former boxing world champion Wayne McCullough. He went through similar mental anguish back in 2000, and fought a 20-month battle with the British Boxing Board of Control. In October that year, McCullough – who today works as a spokesman with the UFC and trains both boxers and mixed martial artists in Las Vegas – had a homecoming fight planned in his native Belfast.

Like Alves, two days before the contest was due to take place, he was told that he had a cyst on his brain. His license was revoked, and he was told that another blow to the head could kill him.

McCullough went back to Las Vegas, and on advice from the Nevada State Athletic Commission, the former Olympic silver medalist and World Boxing Council bantamweight champion had further tests with the neurosurgery department at the University of California, Los Angeles. While there, Dr Neil Martin, having consulted with some of the top neurosurgeons in the United States, had concluded that the cyst was not on McCullough’s brain, but in a space between the brain and the skull.

Martin saw no reason for McCullough to give up his prizefighting career. Although he was then re-licensed in Nevada, McCullough was denied his license again from the British Boxing Board. There followed a protracted, very public battle with the Board, with McCullough eventually regaining his license in 2002. He fought eight more times, three of them world title fights.

“I can remember the feeling like it was yesterday,” explained McCullough, a decade on. “I know exactly how Thiago will have felt. His world will have collapsed around him in that second he was told by his manager. It’s like someone has suddenly locked you in a small, dark room and you can’t get out.”

McCullough’s experience means he knows exactly what Alves went through. “It’s indescribably difficult. The thing you love doing has been taken away and you feel alone, locked inside your own mind. You feel lost, and you don’t know what is happening. You start to think your career is over, even that you are going to die – it was like a twilight zone for me. No matter whether it was two days or 20 months, the feeling is the same – and I really feel for Thiago. It was probably the hardest two days of his life before he found out what was happening, and it is brilliant for him that the issue was resolved quickly.”

Alves concurs, explaining that from prognosis to waking from surgery “felt like the longest week of my life”, adding that once he understood the principles of what was needed he felt so much better. A dark cloud dispersed. “The day I found out that the procedure had been done, a huge weight was lifted. It has made me see a lot of things differently. It has changed my perspective, and it has strengthened my resolve,” he says.

“I feel like I’m just getting started again on a new path,” says Alves of his second chance. “I have so much to achieve in this sport. I know it feels like I have been in this business forever – I’m a young veteran – but I’ve been through a lot since losing to GSP at UFC 100, and over the last year I have been through a lot of changes. Having had this brain procedure – something I never imagined I would have to go through – the worst is now over, and I have even stronger resolve that it is payback time. I’m just keen to get back into action.”

Like many Brazilian fighters, Alves is deeply religious. His faith was one of the things that helped him through the most trying time of his young life. “I thanked God. I didn’t have a chance to go to church over that period; I was in New Jersey then in New York – my first time in Manhattan – but if I had seen a church I would have gone in there and prayed,” he says.

“When I woke up from the operation, my baby, my girlfriend, was there. I woke up and had tubes all over my body, my groin was tight and I couldn’t sleep that night. I wanted to get up but I couldn’t move. It was like playing a mental game. I was praying a lot, then I started to relax.”

Alves will never know what actually caused the issue that forced him to have surgery. “It could have been that my brain was designed this way or I developed it, but the doctor has put what they call a superglue between the vein and the artery. They make a small incision in your groin. Before I went under I asked Dr [Alejandro] Berenstein, ‘Are you cutting my head open?’” Ten years ago they would have, and the mixed martial arts career of Thiago Alves D’Anjou would have been over. Terminado. Final.

I spoke with Alves a week after the surgery. He was in good spirits, relieved and raring to go. He can’t wait for Vancouver, June 12, the rematch with Fitch that has been re-scheduled for UFC 115.

There is a caveat here, however. It has come from Dana White that Alves must not return too soon after his surgery. Although Alves vs Fitch is penciled in for UFC 115, stringent tests will be required before he can fight. “He went to the best doctor in the country to perform this surgery,” said White. “It was a huge success. Before he goes in and fights we are going to get him completely checked out and tested again, plus he still needs to be cleared in the state of New Jersey. We are going to make sure that he is 100% healthy and that New Jersey feels comfortable with it, and then hopefully move forward with this fight.”

Alves has been through a fight, in this case, literally in his own head. He also had to get his mind right. “Psychologically I have been through something, but I’m sleeping much more easily now. I was feeling really depressed and wondered why this had happened to me. It didn’t seem real and I couldn’t believe it had happened to me. After losing to GSP at UFC 100, I changed coaches. I changed some of the people I was hanging out with. All I wanted to do was to become better,” he says. “I want to make history in this sport; I aim to become one of the best fighters ever. I wanted to avenge my defeats by Fitch and GSP, and was doing everything in my power to make sure that it would happen.”

Alves said he has been helped through the last month by his faith and his close friends. “Ricardo Liborio [American Top Team co-founder] was there all the time for me, and although he could not stay for the surgery he helped me through this whole process: Finding out it was not the end for me and what we had to go through with the procedure.”

Then there was the distraught family back home in Fortaleza, in Northeast Brazil. “It was tough on my mom. She was going through a lot of worry back in Brazil – she had picked up the reports on the news and like a typical mom she was worried about them cutting my head open. Would they know what they were doing, and so on,” Alves chuckles. It is good to hear that he has laughter in him again. We can all imagine the emotions the mother of a fighter may go through, a long way away, full of anxiety for her son and soldier.

Alves grows philosophical for a moment. “You know, the upside of this was that it was pretty cool that a lot of people who mattered to me really showed how much they cared about me. I saw through this who I can count on; you see who your real friends are. Like my girlfriend – she really loves me for who I am.”

There were rumors that The Pitbull was back in training four days after the operation. They aren’t true, he says. Though he does admit that he “went for a 30-minute run on the Sunday,” four days after the operation. “There was that feeling, once I was up again, that ‘I’m alive, let’s fight.’ The doctor said that two weeks after the operation I’d be clear again to start training. I’ve had this pitbull locked in this cage for over a year now, and I want to get back in the Octagon.”

Thankfully, the amount of time Alves will spend in rehabilitation has been greatly reduced due to his athleticism. “The doctor said to wait [to return to training] until the incision in my groin had healed – the concern was not wanting the cut in the artery to bleed – but I was in such good shape physically when I went for the surgery, having prepared so hard for the Fitch fight, that conditioning has helped me recover really fast. I do feel lucky, but I’m happy that it [the surgery] is over. I have nothing holding me back now, no fears. I guess I had to go through this and I will go on to become a stronger dude.”

“Through all of this, I want to give a special thank you to the UFC, to Lorenzo and Dana – they are awesome. They called me the day after the surgery, and I’m really grateful to the owners of the biggest show in MMA because they were worried about me. Joe Silva [the UFC matchmaker] was really concerned about me, and so too all of those connected with the UFC. They have really helped me through this,” he says.

In short, Alves – mentally – is back. Barring complications, the Alves vs Fitch rematch will finally take place on June 12. But as Alves’ manager Malki Kawa said: “Thiago found himself very disappointed. He puts everything he has into this sport – but his health comes first.” Amen, to that. Safety first – and it must always be that way.

What's in a name?

Thiago ‘The Pitbull’ Alves is not alone – many fighters bear canine nicknames, with no less than three former UFC fighters (Andrei Arlovski, Rudyard Moncayo and Scott Ferrozzo) sharing the moniker ‘Pitbull’. Alves is probably the one best suited to the name, as his short, stocky, thick-necked frame instantly conjures up images of the famous breed.

Some other fighters who are nicknamed after dogs include: Retired fighter Eugene Jackson, who is known as ‘The Wolf’; UFC welterweight Ricardo Almeida is called ‘Big Dog’ (or ‘Cachorrao’ in Portuguese); Hector Ramirez goes by the bizarre nickname ‘Sick Dog’; and French lightweight Samy Schiavo is simply known as ‘The Dog’. Before he joined Pride in 1999 and was given the nickname ‘The Axe Murderer’, even Wanderlei Silva was known by a dog-themed nickname; his fellow Brazilians called him ‘Cachorro Louco’, meaning ‘Mad Dog’.

Safety first

The UFC’s safety record places it among the safest sporting organizations in the world. Dr Chris Lam, ringside physician for the UFC, explains in detail exactly why pre-fight tests are so important, and what could happen should a fighter with an undetected brain issue step into the ring.

A fighter needs a medical to get a license to fight. A basic full medical test includes an examination of the heart, lungs, and to make sure all of the internal organs are working fine and that there are no joint problems. To get a license to fight, they’ll have routine blood tests done for Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV, etc.

Athletic commissions will ask for a brain scan to look for any structural abnormalities such as cysts and aneurysms, which are the most important things to look for. You can only tell if these are there via a magnetic resonance scan of the brain.

A lot of people walk around normally with an aneurysm and don’t even know about it. Aneurysms can spontaneously rupture, which is why you don’t want those people to fight. I’m not saying an aneurysm will rupture if you’re hit, but you don’t want to take that chance.

Imagine your brain is a ball in a bowl of porridge. If you slide the bowl of porridge and stop it, the bowl will stop but the ball will carry on and hit the side of the bowl. Essentially, if you get hit in the head, that’s what will happen. The head will move and the brain will jerk in the cranial cavity and bounce on the skull. The forces on the brain in the skull can cause the vessels in the brain to bleed.

Depending on where the aneurysm or the bleed is, you will get a collection of blood in the cranial cavity. The more it bleeds, the more it creates pressure on the brain. This blood hasn’t got anywhere to go. You end up with a massive cerebral hemorrhage. If you don’t pick it up in time or get the treatment, you could suffer permanent brain damage or die.

In boxing, before they had anesthetists at ringside, a lot of boxers died because they didn’t get the right treatment quick enough at hospital. Sometimes when you have a bleed on the brain, the breathing can stop – that’s why qualified medical personnel are essential at

any fight.

What happened in Jersey...

Nick Lembo, chairman of the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, is the man who oversees all regulatory proceedings in the state, and was one of the key figures in deciding Alves could not fight on UFC 111. Here he explains exactly how and why Alves was prevented from facing Jon Fitch.

Most fans are aware that fighters must undergo a physical and have bloodwork done, but can you please elaborate on the battery of tests all combatants must undergo prior to an event?

There are different requirements for each jurisdiction. There also may be additional requirements based on the age of the contestant. In New Jersey, at minimum, a fighter must submit a CT or MRI head scan, EKG [electrocardiography], a dilated eye exam by an ophthalmologist, a physical, hepatitis B and C and HIV testing and other blood testing. All fighters are urine tested for recreational and performance enhancers, and some are chosen for blood testing.

At what stage did an issue with Thiago's medicals become apparent?

Dr Sherry Wulkan of the NJSACB was the lead reviewing physician for UFC 111 and picked up on it the same day the medical was submitted to her for review. This was the week of the event. She then conducted additional head testing.

How many medical professionals examined Thiago during the assessment period?

Several reviewed the findings and provided their evaluations.

What was the nature of Alves' condition, and why was it severe enough to prevent him from competing?

It was an arterial venous fistula. According to my understanding from the physicians, it could have leaked or ruptured and resulted in severe consequences. As a fighter, he was at increased risk, but he needed to be treated regardless of his profession.

Have any other instances such as this occurred in the past? Do medicals often pick up undiscovered issues with athletes?

We often pick up medical issues of all kinds, most often head, eye, and communicable diseases are revealed. Some are treatable, some are not.

Now that Alves has undergone surgery to correct his condition, what must he do to obtain a license in the future?

He will be reassessed to make sure the procedure was successful. Thankfully it seems that his condition was of a type that when caught, as Dr Wulkan did, can be completely fixed. Dr. Wulkan then arranged for him to be immediately treated by neurointerventionalist Dr Alejandro Berenstein of Roosevelt Hospital in New York City, a world renowned expert and pioneer in this particular field.